KC Remembers Pearl Harbor, Even Now Memories Outlive Survivors of the Attack

Published December 6th, 2022 at 7:13 AM

Above image credit: In this Dec. 7, 1941, file photo, smoke rises from the battleship USS Arizona as it sinks during a Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. (AP Photo | File)Kansas City has not forgotten to remember Pearl Harbor.

While all area survivors of the Dec. 7, 1941, attack are thought to be deceased, local remembrance of the world-altering event continues.

On Wednesday, the city of Mission will host its annual program devoted to the disaster that compelled the United States’ entry into World War II.

First organized in 1999, the event was in danger of not continuing 16 years ago, when the local Pearl Harbor survivors who had established it began to speak of being too elderly to continue.

A Mission fifth grader asked them to reconsider, and his family assumed responsibility for organizing the program, with the 11-year-old student serving as master of ceremonies.

That fifth grader is today a social science teacher, in part because of the Pearl Harbor survivors he befriended and the stories they wanted him to keep alive.

“I always make sure to have a small lesson about it prepared for my students,” said Quinn Appletoft, 27, who teaches in the Hurley R-1 School District in southwest Missouri, near Branson.

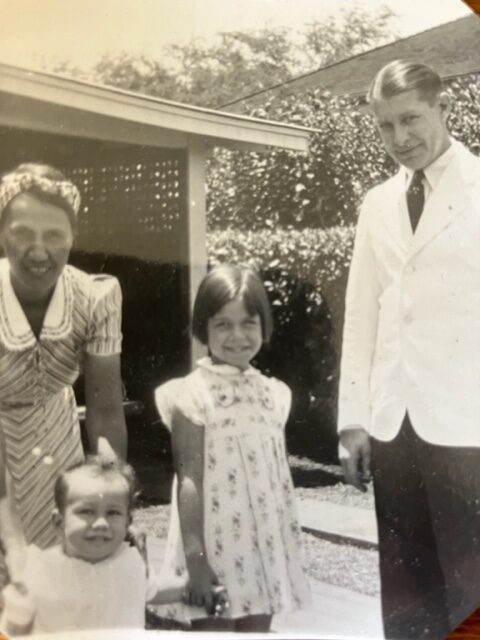

Attending the same program Wednesday will be a retired Raytown marriage and family therapist whose perspective of the attack — as the 6-year-old daughter of a Native Hawaiian mother and white father from Independence, Missouri, in 1941 living on the Pearl City peninsula, a short walk to the water — has proven authentic in the marketplace of World War II memory.

Her eyewitness Pearl Harbor recollections have resulted in a personal multimedia legacy that includes several books and national television appearances, and even the 2017 introduction of “Nanea,” a doll inspired by her backstory and manufactured by the American Girl company, which for years has marketed 18-inch figures invoking specific historical eras and events.

The eight granddaughters of Dorinda Makanaonalani Nicholson were impressed.

They long have known their grandmother’s Pearl Harbor story, the details of which remain vivid today to Nicholson, 81 years later.

“Every December 7, I’m there,” she said last week.

In her mind, she said, she can still step down from the front door of her family’s home, walk down the sidewalk and then look up to see what she later realized had been one of the Japanese torpedo bombers approaching the USS Utah, visible from Nicholson’s street and considered the first of the many American warships targeted.

“l learned years later those bombers had to get low so they could launch their torpedoes,” she said recently.

“The plane was close enough that I could see the goggles the pilot was wearing.”

No Fairy Tales

Wednesday’s Pearl Harbor program in Mission exists today largely due to Quinn Appletoft’s fascination with what began as a bedtime story.

He was a preschooler when his father Ron Appletoft, a former Mission mayor, brought home a children’s history book detailing many pivotal world turning points, one of them being the 1941 attack which killed more than 2,300 American armed forces personnel.

“I wasn’t a fairy-tale type of guy,” the older Appletoft said.

The book’s summary of the attack, accompanied by a dramatic photo of the harbor under siege, riveted his son.

“He would say ‘I want to read about Pearl Harbor again,’ ‘’ Appletoft said.

Quinn was in kindergarten when his father noticed a Pearl Harbor survivors event had been scheduled at Mission’s new Powell Community Center and asked if he was interested in going.

“I just mentioned it out of the blue,” Appletoft said. “I was shocked when he said, ‘Yes.’

“He was pretty shy around the gentlemen, who were very kind to him. The following year I mentioned the program to him again. I didn’t think he would want to go, but he did.

“But I said, ‘This time you have to talk to people.’ ”

Quinn had little problem with that.

“What fascinated me the most was how there was actually a way to connect to that story in real life,” the younger Appletoft said.

“Whenever my dad told me there was an opportunity to meet some of these men, I wanted to know even more about their stories.”

By then Quinn had received his own book on Pearl Harbor, which the survivors signed for him.

One was Dorwin Lamkin, who in 1941 had been a Navy corpsman, or medical unit member, on the USS Nevada. When Quinn encountered him 60 years later, Lamkin was a member of the Metro III Chapter of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association.

Founded in 1958, the organization at one time included some 18,000 members across the country.

That included more than 50 survivors across the Kansas City area. Their motivation: to keep the memory of the attack relevant.

Following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the relevance was clear. The local survivors, when asked, articulated the value of vigilance as well as the need for response.

“I was a young man, just 19, and it was a traumatic experience for me,” Lamkin then told the Kansas City Star, referencing the 1941 attack.

“As a result, I am full of strong feelings about anybody who attacks America, and my immediate reaction to this is that somebody ought to do something.”

Over the subsequent years, Lamkin befriended Quinn, encouraging his interest and giving him other maritime collectibles, such as a bosun’s whistle.

So when the veterans in 2006 began to speak of not continuing their annual observance, both Appletofts were dismayed.

“One thing we asked the veterans was, ‘What are you trying to achieve?’ “ Ron Appletoft said.

“They told us, ‘We don’t want people to forget.’ ”

Some survivors were noticing how, by the early 2000s, the words “Pearl Harbor” had begun to lose their once-universal meaning.

“Some kids ask if it’s a rock group,” Edmund Russell of Lenexa, in 1941 an Army Air Corps butcher at Wheeler Army Airfield in Hawaii, told the Star.

Under new management the annual Mission programs continued, with Quinn serving as convener. Upon advancing to Indian Hills Middle School in Prairie Village, the younger Appletoft made clear to his peers there was no new Pearl Harbor compact disc expected to drop.

“One year we had two busloads of students,” the older Appletoft said. “He packed the place.”

With Lamkin’s encouragement, Mission officials dedicated a small park with benches bearing the names of the local Pearl Harbor survivors.

In 2011 Lamkin led the fund-raising effort to install a metal remnant of the USS Arizona there.

Under Quinn’s continued direction, the annual program continued through his high school years.

“It’s something I feel I owe to them,” Quinn said at the time.

After graduating from Shawnee Mission East High School in 2014, he enrolled at Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Missouri, which prevented him from leading the program personally.

By then, time was taking its final toll.

In 2015, only two veterans — Lamkin and Russell — were available to gather on Dec. 7, so the event took place not at the Powell Community Center but in the private dining room of a Prairie Village restaurant.

“You’re a good egg, Russ,” Lamkin, 93, told Russell, 98, the two of them flanked by members of the local print and broadcast media.

“I’m about to hatch,” replied Russell, who died the following August.

Lamkin, then considered the Kansas City area’s last Pearl Harbor survivor, died in 2019, the same year the last active chapter of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association stopped scheduling meetings.

Of the approximately 16 million Americans who served in World War II, roughly 167,000 remained alive in 2022, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Last year the total number of Pearl Harbor survivors was estimated to be less than 1,500, the youngest of whom would be in their mid-to-late 90s.

But if the local survivors are gone, their stories have been preserved, at least in part to the younger Appletoft, who graduated from college with a social science degree in 2019 and today teaches 5th, 6th and 11th grade students.

“My love of history was always there but my experiences with the local Pearl Harbor survivors cemented the fact that I wanted to teach others about history,” he said.

“I am extremely proud that the annual remembrance continues even when I have had to take a step back from it myself,” he added.

“Each young person who takes an interest and learns more about Pearl Harbor is another person who can carry on its story.”

A Bullet and Shrapnel

The third Pearl Harbor survivor — a civilian survivor — at that 2015 gathering was Nicholson.

Her surprise attack story was cinematic, and had been years in the making.

She and her father, drawn by the increasing din, had rushed out their front door to see the planes overhead.

Moments later military police members arrived, ordering residents to keep their cars off the streets so soldiers could more easily deploy.

Her father disobeyed that order, rushing his family into his Ford and driving to the sugar cane fields above the harbor.

Other families soon joined them before military police directed them to the recreation hall of a sugar cane plantation, where they spent several days before being allowed to return home.

Nicholson still keeps a small handful of shrapnel recovered from their yard, likely from exploding anti-aircraft rounds, as well as a bullet that her father, she said, dug out of their kitchen wall.

“There was no school, and curfews and blackouts started immediately,” she said.

It took her years to realize the value of her specific eyewitness account, unique even among those of other Hawaii residents.

“My experience had been different from most,” she said.

“If you had lived where I went to school, maybe you would have seen some smoke. If you lived up in the hills, maybe you would have seen some of the Japanese planes coming down.”

But her family lived on the Pearl City peninsula, site of the Pan American Airways clipper base where her mother worked.

The peninsula’s residential district included a panoramic view of Ford Island, with the USS Utah on one side and the USS Arizona on the other.

“I don’t think it was until the 25th anniversary that I started to pay more attention,” Nicholson said. “I thought, ‘I better ask Mom and Dad,’ and I’m so glad I did.

“And then on the 50th anniversary, I actually realized I needed to tell my story.”

Prevailing Over bitterness

She first came to Kansas City as a young woman to visit her father’s family.

There she met her future husband, Larry, with whom she reared four sons.

After earning bachelor’s and graduate degrees at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Nicholson began a long career as a marriage and family therapist.

She sometimes would address community and student groups discussing her unique perspective of the Pearl Harbor attack. That led, in 1991, to the invitation from a cruise line to both her and her father to give presentations to passengers.

The trip included a visit to the USS Arizona Memorial, where more than 1,100 crew members have remained entombed in the sunken battleship.

She stopped at the memorial bookstore.

“All the books were written by men, none of them native-born,” she said.

“It was as if the war hadn’t happened to us.”

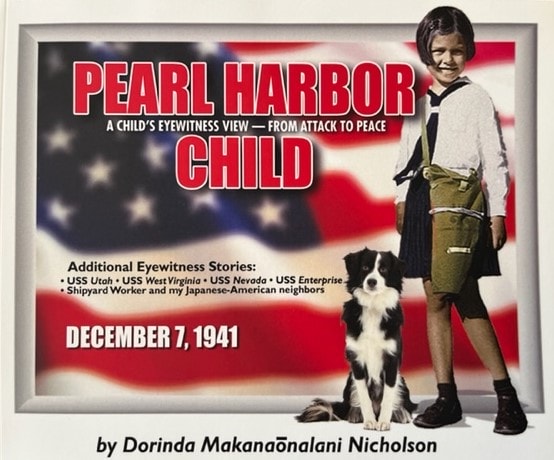

Members of the memorial association asked Nicholson to write her story, and the first edition of what is now “Pearl Harbor Child: A Child’s Eyewitness View – From Attack to Peace” appeared in 1993.

It detailed for younger readers the attack and the subsequent realities of civilian life under martial law.

Non-combatants received government-issue gas masks. Nicholson still has hers.

She and her husband, a photographer and graphic designer, acquired rights to the book and published 11 more editions, expanding the story to include the perspectives of a diverse assortment of eyewitnesses.

Among them were two Japanese-American teenagers who had been forced into a military truck and taken to the same cane fields, but prevented from receiving the shelter Nicholson’s family did.

“They had to stay outdoors in the sugar cane fields, and it rains every night in the mountains in Hawaii,” she said.

In 2001 Nicholson volunteered her own perspective on that year’s terrorist attacks, comparing the shocked disbelief of witnesses to her own reaction to the surprise attack 60 years earlier.

“When you watched the reports from New York, you kept hearing the same things, like ‘It can’t be happening,’ or ‘It isn’t real,’ “ she told the Star.

“There was a sense of being outside yourself, watching it take place in front of you.”

She also noted the country’s sudden unity, lamenting that it took an attack for that to occur.

And yet during that same year of anger, fear and suspicion, Nicholson chose to publish a story of reconciliation.

Her book, “Pearl Harbor Warriors: The Bugler, The Pilot, the Friendship,” detailed the unlikely friendship of a bugler on the USS West Virginia, who watched aircraft approach the harbor, and the pilot of one of those planes.

The book contained testimony from both – Richard Fiske and Zenji Abe – insisting that friendship could prevail over bitterness and animosity.

In subsequent years she took that sentiment across the world.

Ten years ago she and her husband visited the Czech Republic where many, Nicholson said, believe the Pearl Harbor story to contain parallels with the 1938 invasion and occupation of the Sudetenland by Nazi Germany.

Today a video of Nicholson and a group of Czech citizens declaring “Aloha” and blowing a kiss can still be seen on YouTube.

Her emphasis on the experiences of children during war continued to find an audience.

National Geographic approached Nicholson to write “Remember World War II: Kids Who Survived Tell Their Stories,” which featured a foreword by former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

In 2016 Nicholson and her husband published “The Official Pearl Harbor Child Coloring Book.”

At about the same time, a researcher at American Girl came across a copy of “Pearl Harbor Child.”

Nicholson served on the advisory panel for the 2017 manufacture of Nanea.

The doll comes with accessories, among them replicas of the war-time currency then introduced in Hawaii and the government-issued identification card that civilians, children included, could not leave home without.

A companion book, “The Spirit of Aloha,” includes a fictional account of Nanea and her family experiencing the attack, as well as a supplemental appendix detailing how everyday life changed for children under the martial law that was declared.

Even Nicholson’s 2-year-old brother Ishmael received a gas mask.

In recent years she has spoken by Zoom to audiences in both Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

She tells the story of a specific visit to Japan, when she and her husband were house guests of Zenji Abe, the Japanese pilot whose story she had told in “Pearl Harbor Warriors.”

Abe told the Nicholsons he had learned Americans didn’t sleep well on his floor.

“So he said he and his wife, who were both in their 80s, were going to give us their bed,” Nicholson said.

At dusk, the Nicholsons heard a knock.

Abe entered the bedroom, bowed to them, and then turned to offer prayers at his miniature home shrine.

“That’s just what he would have done at 3 a.m on the morning of December 7, offering prayers before he climbed into his bomber,” Nicholson said.

“What are the chances of me sleeping in the bed of a Japanese pilot who may have flown over my house and brought us into World War II?”

But if that event, however unlikely, nevertheless occurred, perhaps it did so because of Nicholson’s resolve to bring her Pearl Harbor story to its best possible conclusion, detailing the friendship of two former enemies and making it available to whoever needs to hear or read it.

“Abe and Fiske chose to pursue the power of peace,” Nicholson said.

“Their gift of their stories to me allowed me to use the power of the pen, which is always mightier than the sword.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author. He is serving as president of the Jackson County Historical Society.