Blue Valley Looks To Forge New Path Can An East Side Area Be A Bellwether For Other Kansas City Neighborhoods?

Blight in Blue Valley includes abandoned homes like this one at 6823 E. 12 Terr., which the city plans to demolish through its dangerous buildings program. (Cody Boston | Flatland)

Blight in Blue Valley includes abandoned homes like this one at 6823 E. 12 Terr., which the city plans to demolish through its dangerous buildings program. (Cody Boston | Flatland)

Published February 26th, 2019 at 6:00 AM

In the United States of the late 19th century, iron works personified the strength and grit of an emerging industrial power.

Pittsburgh became the Steel City, but far to the west, another corner of the industry was growing along the banks of the Blue River — on the eastern outskirts of Kansas City, Missouri. From humble beginnings in the late 1880s, Kansas City Bolt & Nut Co. grew to Armco Steel.

As workers flocked to this rapidly industrializing area, which eventually included a Ford Motor Co. plant along with Armco, the Blue Valley neighborhood became a working-class enclave. Yet jobs and employers dwindled as the U.S. steel industry struggled in the late 20th century, and the Ford plant moved to a new plant in Claycomo, Missouri, that opened in 1951.

So today, Blue Valley is one of Kansas City’s most distressed (and overlooked) neighborhoods.

“We have been put on the backburner a lot,” said Dale Walker, 78, president of the Blue Valley Neighborhood Association.

So Kansas City PBS is zeroing in on Blue Valley and the surrounding area for its coverage of what promises to be a transformative election for the city this year. In June, voters will elect a new mayor and a slew of new city council members. Many of the mayoral candidates are current council members representing districts in and around Blue Valley.

Drilling down to a specific neighborhood spotlights issues that seem intractable and overwhelming in the abstract, such as when people ask how the city can revitalize the East Side.

Our coverage will focus on blight, street crime and economic development, using Blue Valley as something of a testing ground. Perhaps solutions hatched there can work elsewhere — and conversely, can answers in other neighborhoods work in Blue Valley?

From now through June, Kansas City PBS takes a deep dive into the city’s elections by asking:

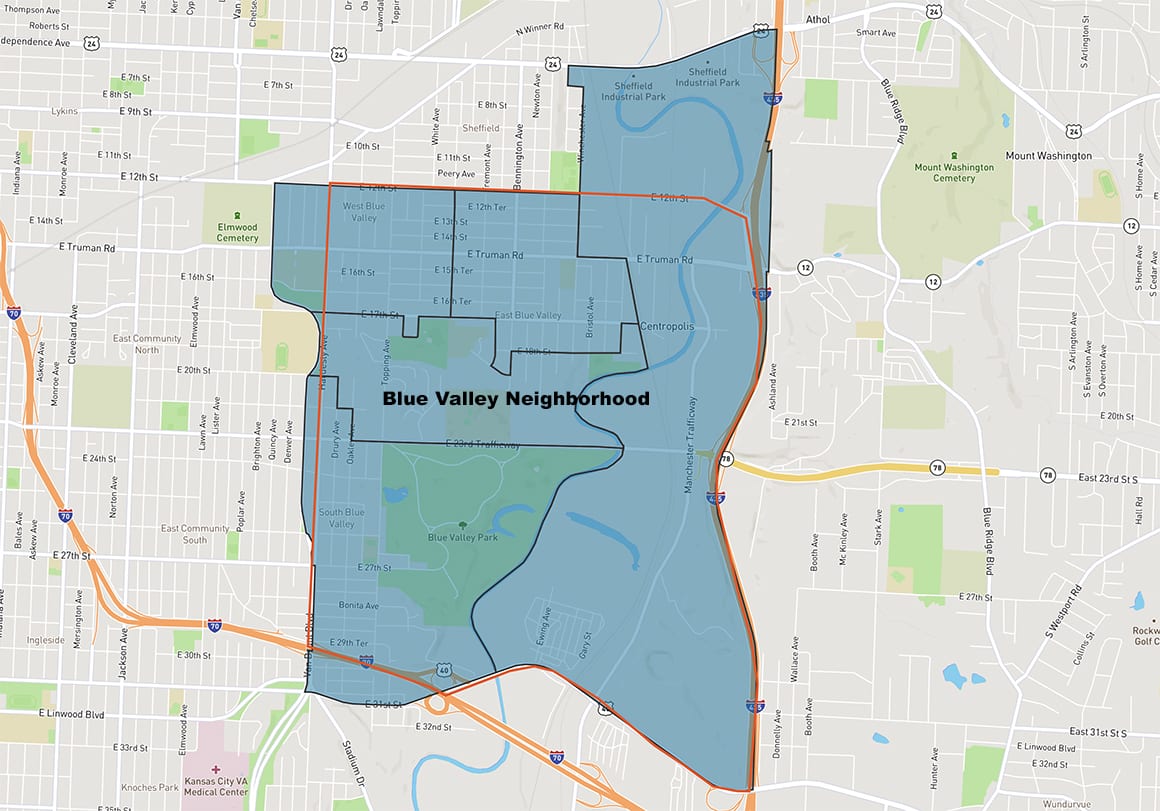

The official boundaries of Blue Valley are: 12th Street to the north; U.S. Highway 40 to the south; Van Brunt Boulevard to the west; and Interstate 435 to the east.

So, how could such a large swath of the city get lost in the shuffle?

Walker thinks his area has gotten caught up in the historic divide along Troost Avenue. There’s an old saying in his part of the city, Walker said: “West the best; east the least.”

Another theory, advanced by City Councilman Quinton Lucas, is that revitalization efforts east of Troost have mainly focused on undoing the legacy of discrimination and segregation in the historically black neighborhoods in the center of the city.

Or perhaps this neglect is simply an outgrowth of the fact that, at more than 300 square miles, Kansas City is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the country. There are just a lot of competing demands, said City Councilwoman Alissia Canady, chairman of the Neighborhoods and Public Safety Committee.

She knows Walker has been beating the drum for his community for years, trying to overcome hurdles like absentee landlords in a neighborhood that is off the beaten track.

“People don’t see the blight in that community to really have the rage he has about why things haven’t changed,” Canaday said.

Canaday is one of the City Council members running for mayor. She represents a district adjacent to Blue Valley, which sits in the 3rd District. The 3rd District representatives are Lucas and Jermaine Reed. Reed is also a mayoral candidate.

Blue Valley’s steel industry was built with investment from England, which gave rise to subdivisions in that part of the city named after industrial cities across the pond. Those vestiges live on today in neighborhoods like Sheffield and Leeds, and in major roads, such as Manchester Trafficway.

Other features of today include Blue Valley Park, the Sheffield Industrial Park at 12th Street and Winchester Avenue (where Armco and the Ford plant once operated) and decrepit housing.

Roughly a third of the housing stock in the neighborhood dates back to 1939 or before, according to census data analyzed by mySidewalk, a data firm based in Kansas City, Missouri.

And, like much of the East Side, Blue Valley is checkered with sections where roughly a quarter of the homes are vacant, according to the city housing plan. In many areas in and around Blue Valley, the median sales price of a home is approximately $6,200.

Residents are also at risk from a number of buildings that could collapse at any moment, and they are surrounded by vacant lots that are often overgrown breeding grounds for pests.

City crime data also shows that, combined, the two main ZIP codes encompassing Blue Valley recorded more than 12,000 incidents last year, including everything from pickpocketing to murder. That was nearly 10 percent of the citywide total.

Blight, crime and disinvestment are interrelated.

Residents flee areas when jobs evaporate, not even bothering to lock the door on a property that becomes someone else’s problem. Left behind are the elderly and the poor.

The question then becomes: How do you reverse the process?

If you crack down on crime, will businesses and residents return? If the city incentivizes businesses to open in the area, will the neighborhood rebloom? If you lure new residents to rehabilitated blocks, will the ripple carry forth to surrounding areas?

For Walker, the answer is simple. “We have to stop the crime,” he said. “That is all there is to it.”

For instance, he asked, What good is it to replace sidewalks if people are too afraid to use them? Guns and drugs are the big problem, Walker said.

The best way to combat crime, he argued, is to return to the days of community policing. Cops need to be back in restaurants eating breakfast with the locals, Walker said, not blazing along streets — sirens blaring — heading from one crime scene to the next.

Walker would get no argument against that from many of the elected officials representing Blue Valley and its environs. The larger debate is whether that policy requires additional police officers; the city added two dozen last year.

You can count Lucas, and some of his other mayoral rivals, in the camp of wanting more officers. More eyeballs, Lucas said, can deter drug dealing, prostitution and other nuisance activity in places like Blue Valley.

As for economic development, Blue Valley offers an opportunity to further the discussion about economic development incentives and ways to enhance quality, affordable housing.

Could this election, for instance, mark a harder turn away from granting tax incentives to developments downtown and in the Crossroads? There is certainly a mood among some candidates that these tools have achieved their purpose in those areas and should be redirected to struggling places like Blue Valley.

And on housing policy, one of the biggest questions is whether it’s best to rehabilitate the housing stock or build anew.

If these seem like long-term solutions, don’t tell that to Walker, the head of the neighborhood association. Asked when he thought his neighborhood would be thriving again, he said, “I think it’s going to take five years. Five years. Something like that.”

This year’s municipal elections in Kansas City, Missouri, promise sweeping political changes in the metropolitan area’s largest city. A new mayor and a host of freshmen council members will emerge when the final votes are counted in June. Kansas City PBS will focus its election coverage on three topics that these new elected officials will face: affordable housing, violent crime and business tax incentives. We will tell our stories from some of Kansas City’s most hard-pressed neighborhoods. Keep tabs on our coverage by following us on social at #WhoWillLeadKC