Help With Navigating a Complex Media Landscape Media Literacy Courses Teach Valuable Skills to Students of All Ages

Published December 21st, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Students decided in October that gun violence would be the broad topic for their panel event with American Public Square. (Cody Boston | Flatland)Eliza Welch, a junior from Belton High School, often feels like she’s drowning in the flood of information shared on social media.

“I feel like social media is something I use to get my feet wet about a topic because anyone can go online and say a bunch of stuff,” Welch said. “Most of the time I’m just like ‘What are you even saying right now?’ and try to do some digging on my own.”

Welch is one of 70 students participating in the American Public Square civic education initiative, which among many topics includes media literacy education.

Students from seven area high schools recently settled on “gun violence” as the topic for their American Public Square panel event in the spring. The group gathered at the Country Club Plaza branch of the Kansas City Public Library to narrow their focus with help from local journalists and a presentation urging them to “think like a journalist and act like a fact checker.”

In its 2023 Digital News Report, the Reuters Institute found that just 32% of Americans have an overall trust of the news. The same report revealed a dramatic increase in the percentage of consumers who find their news online and via social media.

Reuters reported that folks who find their news on newer forms of social media, such as TikTok and Instagram, pay more attention to celebrities and influencers than journalists and news outlets.

As the U.S. approaches another polarizing presidential election and continues to be swept into a sea of information, how do folks decide what is true and who to follow?

Flatland on YouTube

What is Media Literacy?

Put simply, media literacy is the ability to discern useful and trustworthy information. It’s always been an important skill, but it’s especially important when consumers have unlimited access to information via the internet and an added onslaught of content increasingly created using artificial intelligence.

Ashley Muddiman, associate professor at the University of Kansas, said if people are given a choice, they will be more inclined to select news from programs that tend to agree with their partisan perspectives.

Muddiman, who studies communications and the effects of political media, explained how news and social feeds are shaped by an individual’s “filter bubble.” Because digital spaces can be personalized and users have so many choices, they’re only seeing information that agrees with them all the time.

“The filter bubbles, both of the user’s and the algorithm’s making, cause us to never see information we disagree with,” Muddiman said. “This isn’t totally the case, but when people have the option to select information that agrees with them, they tend to take it.”

Michelle Smirnova, associate professor of sociology at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, tries to challenge her student’s biases.

She doesn’t use textbooks in her classes and instead teaches students to analyze books from various perspectives and by distinctly different authors.

She spends time fleshing out the potential “standpoint” these authors may have to help give context to her students as they make their own judgments.

“With the upcoming elections and the claims of fake news in the past, it’s obvious that there’s been an increase of distrust in the American people,” Smirnova said. “We automatically jump to, ‘How can we verify that?’ And (as educators, we) want to teach students what a valid, credible source is and the process of verifying. But it can be a hard thing to teach at all levels.”

Smirnova said there must be a democratization of sources. Folks who want to put their media literacy skills into practice must diversify their news intake.

“People want to have information from the ground and through people’s experiences versus media conglomerates, but we also want to be able to evaluate credibility too,” Smirnova said. “In some ways, we’re seeing positive outcomes of new technology and information from social media and personal accounts, but there’s a bunch of challenges that come up too.”

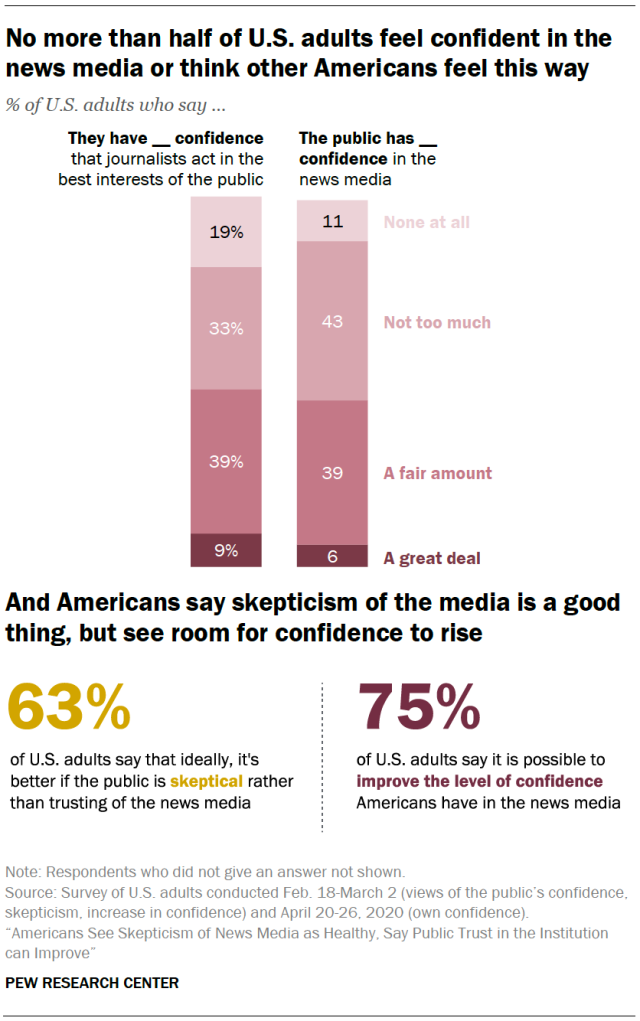

Data from Pew Research Center shows distrust of the media from 69% of Americans stems from careless reporting (55%) or a the perception that media seeks to mislead the public (44%).

Shakey Public Trust

Today’s complex media landscape also is marked by parasocial relationships, or one-sided relationships with an influencer, newscaster or podcaster that feel more like a personal connection than just someone online.

“As we see the people’s trust declining from these major institutions, I’m curious if people are basing their trust on interpersonal relationships or parasocial relationships,” Smirnova said. “Even though they don’t know them personally they feel like they do know them.”

Parasocial relationships can have positive effects. But they can also contribute to anxiety, social isolation, depression and increased spending habits.

Smirnova said these online relationships help the consumer create or form a bias, and thus feed into an already content-mongering algorithm.

“When someone shares something, their mutual friend is likely going to believe the information — not because of whatever link is attached, but rather because it’s from someone they already trust,” Smirnova said.

Smirnova encourages her students to “follow the information trail,” and ask questions about where information is coming from and the context in which they’re seeing it.

These are key elements of media literacy education, and the same questions that the National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) encourages media consumers to ask themselves.

Educators like Muddiman and Smirnova teach these skills to their college students, but elementary and secondary school aged students are the primary focus of media literacy efforts.

Media Literacy Now (an organization encouraging media literacy policy across the country) published a survey in which 62% of adult respondents did not learn how to analyze media messaging while in school. The survey also found 84% of respondents believe media literacy education should be required in most states.

Legislative Efforts

For the past three years, there have been efforts in Missouri to enact a statewide media literacy policy. The initiative started after Rep. Jim Murphy (R) from St. Louis learned about the issue from one of his constituents.

“If we don’t teach our children how to process all the information they’re receiving, I think it’s going to be a continuous struggle to bring forth a generation of people that understand what they’re seeing and why they’re seeing it,” Murphy said.

The Media Literacy and Critical Thinking Act, sponsored by Murphy, would establish a media literacy and critical thinking pilot program, guided by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, to study the most effective lessons and resources in media literacy education in Missouri.

Five to seven schools would participate in this two-year pilot program to inform future statewide K-12 standards. Pilot program sites would be instructed to develop strategies for each element of media literacy, such as news content, visual literacy (images, videos), digital literacy and social media behavior.

“In (journalism) school they taught journalists how to verify information,” Murphy said. “We almost have to do that with our kids now … What we really have to do is teach our kids how to question and how to verify and how to question internally what it is that they’re hearing.”

Murphy said the effort also connects with cyberbullying and youth mental health. If students are taught to evaluate the information they consume, there’s a hope that they’ll be less likely to internalize things they see online that are potentially harmful.

The act did not advance in 2023 but has been pre-filed for the upcoming legislative season. Murphy is hopeful it will be passed in 2024.

Efforts in Missouri are part of a growing wave of media literacy legislation across the country.

Shawn Healy, the senior director of policy and advocacy at iCivics, works to strengthen state policies around civics education across the country, supporting the mission of the nonprofit started by former Supreme Court Judge Sandra Day O’Connor.

“(Media Literacy) is critical, not just in civics … but it is just a core facet of what it means to be an informed citizen,” Healy said.

Healy noted that Missouri’s bill would provide resources to the pilot program and for implementation.

“Teachers are making that assumption often, that because young people are so comfortable with devices, that they adapt to information literacy,” Healy said. “So, teachers need training (and) they need access to high quality curriculum and materials to do it.”

Last spring 20 states proposed legislation around media literacy and several bills have been proposed federally.

Most of these bills have bipartisan support, but sometimes civic education bills can get thrown into divisive political arguments around race or gender education policies.

“There’s a lot of noise out there, but I think there is a broad consensus that we need to do more when it comes to civic education and … information literacy,” Healy said.

Media literacy education tends to be aimed at schools. But adults could benefit just as much — if not more — from the same type of lessons.

“This is a population-wide challenge,” Healy said. “The challenges, I think, are most acute amongst older generations, actually.”

It’s harder, however, to facilitate adult information literacy courses because there are fewer common institutions in which to engage.

“It’s why we’re so passionate about K-12, because … it just gets harder to get to people as we get older,” Healy said.

School and public libraries are often epicenters for media literacy education.

Locally, the Kansas City Public Library hosts events for all ages throughout Media Literacy Week in October, and regularly integrates elements of media literacy education into its programming.

Kansas City Public Library, and most public libraries, also offer online access to a wide variety of local and national news sites and databases with a library card.

It’s not just reporters and public figures who need to be conscious of what they’re sharing. Everyone has a role to play in stopping the spread of misinformation — especially when everyone can share, repost and comment.

How to Be More Media Literate

Muddiman’s research found that when it comes to political news, consumers are repelled by instability and rage.

“They either are not likely to read/select that information even though it is quite negative and the conflict is very high, or they’re likely to select information that emphasizes bipartisanship and problem solving, rather than that bickering between politicians,” Muddiman said.

She is encouraged that most people crave solutions-based politicians rather than those who fight.

She sees the same trend in social media discourse. When someone critiques an article with credible sources, viewers are more likely to pay attention to the accurate information.

“People need to learn how to share correct information,” Muddiman said. “Even if they aren’t trying to change their followers or friends’ minds, research states that viewers of misinformation are actually less likely to believe it.”

The opinion of the person who originally posted, or started the conversation might not change by simply sharing the correct information, but it can help others in the conversation.

Misinformation can spread easily in emotional situations, or when there is a lot of distance from the events.

Muddiman said in these cases, especially around foreign events, she turns to trusted news organizations before trying to share any information. They might not have all of the on-the-ground updates, but at least she knows that information has been verified.

“Again, that’s a little tougher to do because not everybody has news organizations they trust,” Muddiman said. “I think one of the biggest ways to solve this problem is building the trust back up between mainstream news organizations and the public.

Pew Research Center found 77% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning Independents say they have some trust in national news outlets. Only 42% of Republicans and Republican leaners agree. This aligns with previous research showing that party is the strongest factor in the public’s broader attitudes toward the news media.

That’s why Smirnova said it’s so important to engage with people and news outlets who have differing opinions, to “almost trick the algorithms.”

“I think getting off the internet and talking to humans who have different perspectives than you and asking them what they consume can help,” Smirnova said. “By seeking out, deliberately, information that’s from a perspective you disagree with, that’s how you can help create your own opinion.”

She also teaches students to be aware of their own biases and to keep their emotions in check when reacting to information.

“We all see differently based on where we are standing,” Smirnova said.

“When you’re reading uncomfortable experiences, you feel your blood boiling,” she said. “It becomes impossible to hear what’s being said because you probably have a ringing in your ears. Challenge yourself to take a step back and listen empathetically.”

There’s hope yet for a more media literate future.

Max Hunt, a senior from Lee’s Summit West High School who attended the event, said his generation can better evaluate and discern the information they find online, because they’ve had media literacy education.

“I feel like it’s a lot easier for us to understand it because we’re being taught about it earlier,” Hunt said. “There’s so much out there for us to be able to learn from and about, it’s easier for us to navigate weeding through all the fake stuff and all the inflated stuff.”

Disclosure: Members of Flatland staff helped to organize the media literacy event with American Public Square, as fellow members of the KC Media Collective.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Cody Boston is a multimedia producer for Kansas City PBS and the producer of “Flatland in Focus.” Nicole Dolan is a freelance reporter, assisting with “Flatland in Focus” on Kansas City PBS. Julie Freijat, a masters student at the University of Missouri and a Flatland contributor, assisted with visualizations.