The Post-Pandemic Health Care (Staffing) Crisis Here’s What Health Workers Saw, Want and Need, and Potential Solutions

Published March 17th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

It’s been a heavy two years for Dr. Carla Keirns.

Keirns, a palliative care physician and medical ethics professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, has worked on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic. She not only worked bedside but also worked as a clinical ethicist, advising patients and families about their rights.

Then, in April 2020, her work and home life collided.

“I was seeing patients myself and I told my team: ‘You know, my father-in-law has COVID. If something happens, that could disrupt my day,’” she recalled.

That day, just an hour later, he died. At that point, she said, her team came to grips with the gravity of this new virus and its new patients.

Fast-forward one year. The delta variant hit.

“As delta was rising. I saw 22 patients on Saturday, and by Monday morning, 12 of them were dead,” Keirns said. “Even in my line of work, that’s unusual.”

Keirns saw nearly six times as many patient deaths as normal. While palliative care physicians are experts in end-of-life care, COVID accelerated the death rate.

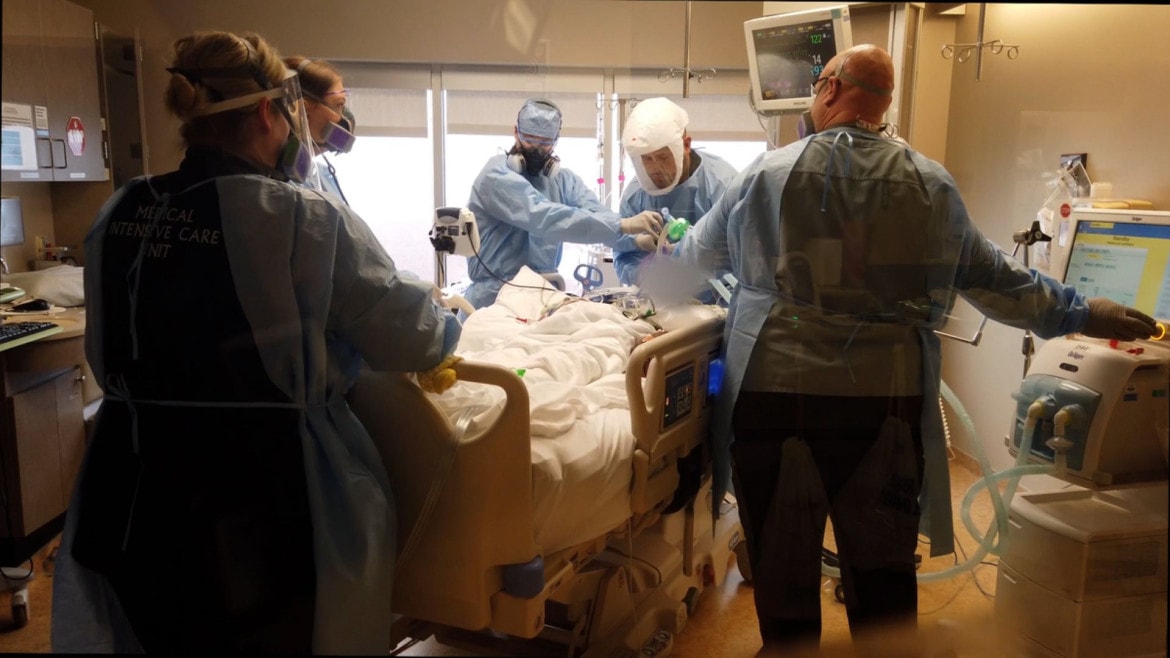

An unprecedented crisis forced health care workers to triage care. They worked long hours and were isolated from their own families, all while caring for the strangers constantly streaming into their hospital corridors.

At the beginning of the pandemic, health workers were applauded. Midway through the prolonged pandemic, some folks began to hurl insults and disparage the workers trying to keep the virus at bay.

A text from a Kansas City nurse Lauren Hermann put the experience during COVID like this: “The emotional whiplash of going from ‘heroes’ to ‘puppets of the leftist agenda’ is staggering. It’s heartbreaking.”

Another wrote: “I’ve experienced more burnout and compassion fatigue and trauma from this job than I ever thought possible.”

Young nurse Silvya Zamora graduated in 2019, only to begin working just as COVID hit.

“Pandemic nursing is my normal,” Zamora said, adding that it was “scary and isolating.”

Zamora had to constantly adjust to new guidelines that could shift hour to hour.

“When we were in the thick of it in the beginning, one of the ways that teams were sorting through these morally distressing issues was like who’s younger who’s healthier,” she said.

Beds were full. Nurses were overtaxed with the number of patients they had to care for. With no one to turn to, she kept working.

“Who else would (work) if you took a mental health day?” she said.

“It was just a really long time to find a silver lining. And I don’t know if to this very day I have found one.”

Tired. Detached. Frustrated. Sad. Angry. Overwhelmed.

These are all common feelings among nurses, physicians and other health care staff. It’s also a sign of burnout and what some researchers call “moral distress.”

Burnout, as much as the virus, has become endemic in the health care profession.

One long-term care nurse said in a text to Flatland: “Burnout is so much a part of the medical field now that doctors and nurses just often don’t have time to really consider a problem that isn’t easily obvious.”

‘Pushing a Rock Uphill’

Then, those workers began to leave.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that the health care sector has lost more than 300,000 workers since February 2020.

At the depth of the staffing crisis last fall, when the sector had lost more than 500,000 workers, a Morning Consult survey found that one in five health care workers had quit during the pandemic.

In 2020, health care employment plunged. Unlike previous recessions where health employment remained fairly steady, with a few minor decreases, from March 2020 to April 2020 employment fell by 9.3%.

“Public health is one of these things that we underappreciate when things are going well,” said Dr. Mario Castro, a critical care physician leading a recently launched long-COVID study at the University of Kansas School of Medicine.

Castro said as cases skyrocketed in early 2020, chief medical officers, doctors and leaders in health care rallied for early morning conversations about what to do next. Month after month area hospitals and emergency systems struggled to catch up.

During an Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Coordinating Committee meeting in January, several EMS speakers, who were audibly flustered, said triaging care became difficult and communication breakdowns were happening left and right.

One EMS worker said the strain was so bad that one time two ambulances were dispatched for one patient. He called it “ridiculous” considering the staff shortages.

“You feel like you’re just pushing a rock uphill,” said Jason Glenn, a historian of philosophy of medicine at the University of Kansas Medical Center. “Psychologically, that takes an even deeper toll on health care professionals who are there in the trenches.”

Glenn drew parallels between pandemic health care workers and soldiers fighting in Vietnam. In war, soldiers who might not have wanted to fight continued to do so for their fellow soldiers. The same happened to nurses, physicians and other staff during the pandemic crisis.

“A lot of providers who expressed that the only reason that they were showing up for work was because they knew if they didn’t, it would be harder on their colleagues,” Glenn said.

Work in the trenches of health care unearthed some ugly truths.

“Pandemic nursing is my normal.”

Silvya zamora, registered nurse

Zamora, who grew up near 27th Street and Jackson Avenue in Kansas City as a child, confronted realities her own family lived through. One vivid example came to mind.

“People who (were) admitted to the hospital with COVID and are using a family member’s name because they’re not documented,” she said, adding that “the pandemic put a microscope on all these (societal) concerns.”

After they were admitted, Zamora had to pull them aside to explain next steps with the patient if any complications arose. The most vexing issue, she said: “If you die under this name, how will (we) fix that?”

It also added stress.

The way the pandemic was unfolding was compounded by a preexisting – and well-known – staffing problem.

Shortages in the nursing sector were projected as early as 2018, according to the U.S. Registered Nurse Workforce Report Card and Shortage Forecast. When COVID hit, those numbers shot through the roof.

Health care workers quit. They were laid off. And some died.

Among health care as a whole, nurses and support staff were more likely to die than physicians, according to a joint Kaiser Health News and Guardian report. In the first year of COVID, more than 3,600 health care workers perished.

Moreover, roughly two-thirds of health care workers who died were people of color.

What’s Next?

The trauma of treating and watching patients, peers and family killed by COVID has caused collective exhaustion. And the staffing shortages amplify what’s missing.

That is why Samuel Ofei-Dodoo at KU School of Medicine-Wichita started a mindfulness program. In his research, he found that people who worked directly with COVID patients were in work mode for so long, they found no respite.

Those workers were three times as likely to experience professional burnout than those who did not treat COVID patients. The first dimension of burnout is physical and emotional exhaustion.

“You feel depleted. The second dimension of burnout is cynicism. That is the interpersonal component of burnout,” Ofei-DoDoo said.

Not only does burnout affect the health care professional, but it also affects patient care and ultimately the health care system as a whole.

Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, agreed. His expertise is in infectious disease, critical care and emergency medicine, with a focus on pandemic preparedness and biosecurity.

Adajla’s scholarship has focused on what the pandemic taught so leaders can find ways forward.

“It’s not just about dealing with the pandemic,” Adajla said.

In crisis mode, hospital staff was forced to choose between taking care of COVID patients and taking care of trauma patients. Some had to put off surgeries and essential screenings, or cancel drug and alcohol therapy sessions.

The lasting fallout from that, Adajla said, is dangerous.

“We have to remember that in a pandemic, you can’t just privilege the short term and not think about the long-term consequences, “ he said. “What you need is a sustainable approach.”

That’s what health care staffers say they want. Many were faced with caring for their patients 100% or their family.

Arel Roxas Bansil, a traveling ICU nurse, felt overwhelmed in the hospital setting and at home. Bansil is a new father and found himself neglecting his family after several long shifts.

“I’d come home after three, four shifts to take care of a human being, a life,” he said. “Then I’d come home and take care of another one.”

“It’s very very hard to take care of someone when you haven’t taken care of yourself.”

Bansil has taken steps toward self-care but his hope is for institutions to recognize the need to provide support for his peers.

A new program at Kansas City University, THRIVE, aims to curb burnout by building health care students’ coping skills and resiliency. The pandemic shed light on the issue, but a lack of work-life balance, self-care and overwork has long been a problem in the health care sector, studies show.

“We need people to be OK with not being OK,” said Carlton Abner, associate provost of Health and Wellness at Kansas City University.

Announced in February, KCU is the only school in Missouri to earn a $1.5 million grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration, part of HRSA’s Health and Public Safety Workforce Resiliency Training Program. The money will be disbursed over three years.

With that money, KCU launched the THRIVE program to support early career health care workers navigate the challenges they may face. The focus is on resilience.

“This is something you can actually develop, but it doesn’t mean anything is missing from you,” Abner said. “Resilience and reducing burnout is simply pointing your mind in a different direction.”

But, Abner acknowledged, other factors come into play for folks on the front lines. There is a need for leaders of health institutions to employ equitable compensation, mental health support and policies.

A few points he mentions were wages that remain stagnant across the board and imbalanced patient-to-staff ratios.

As a former emergency nurse, Abner understands the risk and amount of stress the current health care staffers have been under. He said it’s more important now for folks to share openly what they need and for institutions to support those workers.

They have, and there’s more work to be done.

“We want safe staffing and hazard pay and instead they give us branded lunch boxes – as if we have time for a lunch break,” one nurse told Flatland.

The consensus among health workers is they wished they had been supported sooner. Many simply want to be seen.

“Workers across society need to feel that their welfare is respected and recognized and appreciated,” Keirns said.

Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs for Kansas City PBS. Cody Boston is a video producer for Kansas City PBS. Catherine Hoffman covers community affairs and culture for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.