Guest Commentary: Turning Toward Greatness, Before We Get to Detroit

Published April 1st, 2020 at 12:15 PM

(Editor’s note: This presentation that’s been making the rounds of local civic groups recently offers a strong public policy and economic case for continuing to reinvest in our urban core, the so-called River-Crown-Plaza corridor, and nearby neighborhoods.)

By Dennis Strait, managing principal, Gould Evans

Communities across the country face a fundamental problem: we’ve built cities we can’t afford.

Newer bedroom communities are beginning to see their infrastructure crumble. Older cities, well-past that stage, are scrambling to find resources to stay afloat. Some have even declared bankruptcy, Detroit being the national poster child.

Kansas City can steer away from becoming Detroit, and instead become a model for other American cities. This path toward prosperity — and ultimately, resiliency — starts with three steps forward:

1) Recognize what brought American cities to this point.

People have been building cities for nearly 5,000 years. Through generations of trial and error, we learned to build for the most convenience we could afford.

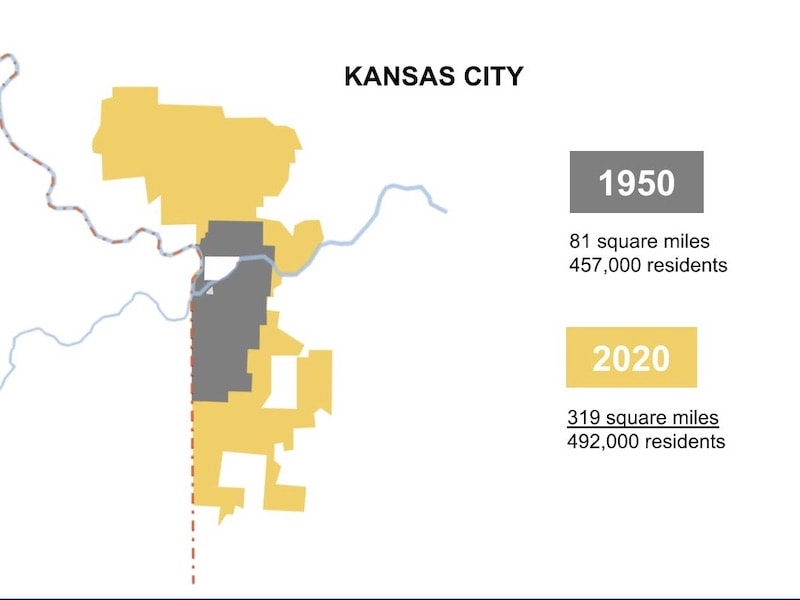

Between 1850 and 1950, Kansas City grew from a small village on the Missouri River to a full-fledged city of nearly a half-million people, all within 81 square miles.

We built an impressive downtown skyline, a nationally recognized system of parks and boulevards, and — stop and think about this — nearly 100 miles of streetcar lines.

These accomplishments didn’t require years of campaigning. They simply followed our ancestors’ successful patterns of city-building, patterns that emphasized proximity to shops, schools, transit, and work.

Kansas City ballooned geographically following World War II, but its population growth lagged far behind. (Graphic by Gould Evans)

By 1950, most American families owned a car and our tradition of city-building dramatically shifted. Suddenly, with newfound mobility it was easy to drive 15 miles in 15 minutes, so we did.

Combined with a new highway system and an unprecedented postwar demand for housing, cities exponentially expanded their boundaries to capture less expensive land. The convenience and affordability were undeniable, but as we’re now learning, the growth was short-sighted.

Today, at 319 square miles, Kansas City is nearly four times as large as it was in 1950, and most of that new land is outfitted with infrastructure. Yet the city’s population has hardly changed.

As a result, each resident is responsible for at least four times as much infrastructure as our predecessors.

While Kansas City grew more than most U.S. cities, many are in the same predicament. Geographical growth, without a corresponding growth in population, is fundamentally why cities struggle to afford the infrastructure they’ve built.

Over the past 70 years, we’ve extended our boundaries, but not kept-up with associated costs of infrastructure.

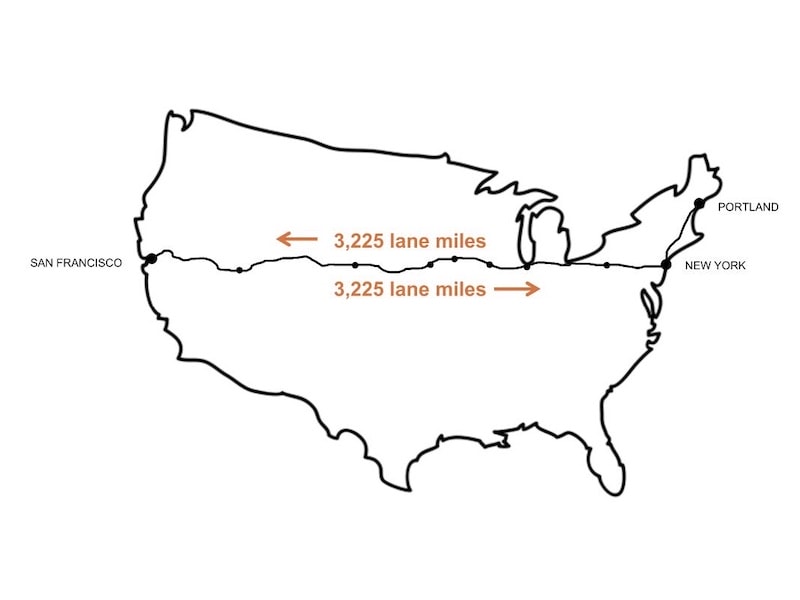

In 2019, Kansas City could afford to budget only 10 percent of what our Public Works Department recommended to return the condition of our streets to “fair” — not to good or great, just fair.

Deferring maintenance doesn’t postpone costs; it accelerates them, since poorly maintained infrastructure tends to fail faster.

Kansas City has to maintain enough street lanes to pave a two-way road from San Francisco to New York City with enough left to extend to Portland, Maine. (Graphic by Gould Evans)

We publicly debate the feasibility of programs and services to cover this new burden of infrastructure liability, but are left with band-aid approaches, filling potholes without fixing the underlying, crumbling streets.

We could consider a tax increase, but that is an unlikely solution. Rather, we should focus on city policies that encourage more productive patterns of development, moving us back toward more sustainable levels of infrastructure per person.

2) Pay closer attention to our development patterns.

Prior to 1950, we understood how to make efficient use of infrastructure. Out of necessity, we followed development patterns with higher ratios of private development to public infrastructure.

These efficient patterns resulted in neighborhoods that were highly productive in terms of the tax revenue returned to the city. Financial people think of this as return on investment or ROI.

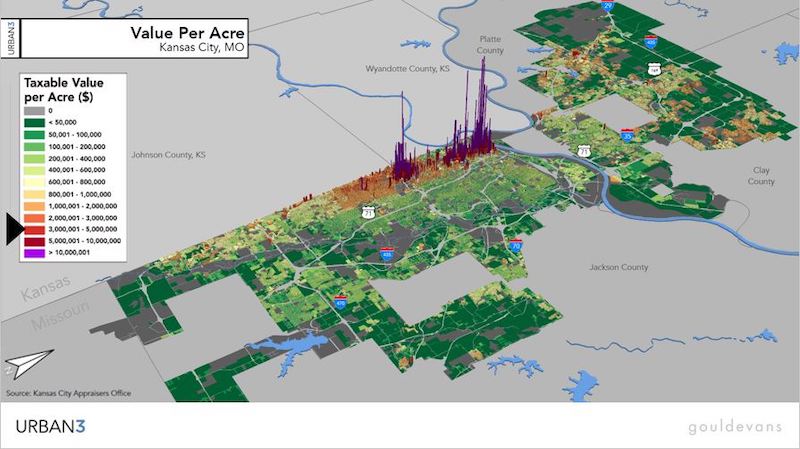

As owners of our city, we should insist on sufficient returns on our investments in infrastructure. With this understanding of productivity, efficiency, and ROI, an obvious pattern emerges when comparing a downtown area to a suburban neighborhood.

A study funded by the Kauffman Foundation and completed by the planning firm Urban3 (full report here) reveals in the illustration below that (emphasis added) our downtown produces dramatically more infrastructure ROI than the rest of the city.

There are other scattered spots of good ROI, but the 16 miles that comprise the central part of Kansas City — from the river to 63rd Street, between State Line Road and Troost Avenue — are clearly our economic engine.

Urban3’s ROI heat map illustrates another, less obvious point about development patterns — the high productivity of pre-1950 residential development including most of our midtown and downtown neighborhoods.

This chart shows how the value of land in the urban core including downtown, Midtown and the Plaza, far exceeds the rest of the city. (Graphic by Urban3 and Gould Evans)

Prior to 1950, neighborhoods included a blend of housing types including single-family homes, duplexes, triplexes, and multi-unit buildings, like the three-story “colonnade” apartments found throughout our central city neighborhoods. This variety of housing types created high infrastructure ROI.

However, in the years since 1950, we expanded our neighborhoods with larger lots limited to just one type of development: the single-family home.

Without the added intensity of a variety of housing types, our post-1950s neighborhoods are three to five times less productive in terms of tax revenue than our older midtown neighborhoods like Hyde Park, Columbus Park, the River Market, and the Westside.

We can make better use of our existing infrastructure by learning from productive development patterns in our downtown and pre-1950 neighborhoods. With higher returns on infrastructure investments, we can steer our city away from increased financial insolvency and toward resiliency.

Productive development patterns generate robust revenue to our city budget, which then fund infrastructure maintenance, health, safety, education, shared public spaces, and all the other attributes that make cities truly great.

Addressing our city’s fiscal health in this way is an important step to position Kansas City as a national leader, but true resiliency should also prioritize inclusivity.

3) Allow all community members to share in prosperity.

There’s an obvious anomaly in Kansas City development patterns. Across one particular street from our city’s 16-square-mile economic engine, property values drop tenfold.

This lower-valued part of Kansas City has the same development pattern as the highest-valued part, and even meets the same three rules of real estate: location, location, location.

Wonder Shops + Lofts occupies the former Wonder Bread bakery at 30th and Troost. It’s part of a growing revitalization trend along the street.

That street is Troost and the under-valued location is our east of Troost and Northeast neighborhoods. Urban3’s findings clearly link this result to a history of redlining and other exclusive public policies that removed value and denied prosperity.

Over the last few years, the Downtown Council of Kansas City, the Civic Council of Greater Kansas City, and the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce have prioritized equity and shared prosperity in their community agendas.

This provides a path for Kansas City to reimagine its public policy to promote equitable and incremental development.

We now have an opportunity to uniquely position Kansas City as a visionary community. With an understanding of the source of our infrastructure challenges, we can leverage city policy to encourage productive development patterns.

Financially sustainable development can help our city begin to build a buffer for future economic shocks, strengthening resiliency in a rapidly changing world and creating a shared prosperity for all residents.

Instead of continuing to build cities we can’t afford, let’s take advantage of this opportunity to finally afford — and thrive in — the beloved city we’re building.

Dennis Strait is an architect, planner, landscape architect, and the Managing Principal of the Kansas City studio of Gould Evans, a nationally recognized planning and design firm. His 37 years of experience involves community planning and a wide variety of private, civic, and educational facilities.

Recently, he and the firm have partnered with the Kansas City Public Library on the Making a Great City speaker series to raise public awareness about development patterns that build our city’s value and financial resiliency.