Mending Our Broken Heart: Downtown Revival Hinges on Housing (Part 1)

Published September 26th, 2022 at 11:30 AM

“Downtown KC: Mending Our Broken Heart,” was a groundbreaking series originally published by The Kansas City Star 20 years ago this month.

It was written by former staffers Jeffrey Spivak, Kevin Collison and Steve Paul, with photographs by Rich Suggs. It was edited by former deputy national editor Keith Chrostowski.

CityScene KC thanks The Kansas City Star and Mike Fannin, its president and editor, for granting permission to republish this report.

While The Star retained the text of “Mending Our Broken Heart,” the original photos and graphics were unavailable. Photos of that missing material from a reprint of the series were used as much as possible.

What John and Sharon Hoffman were doing wouldn’t be startling in Chicago, Denver or Indianapolis. But in Kansas City, it provoked an incredulous question from friends: “Are you crazy?”

They just couldn’t understand why the society couple gave up their off-Ward Parkway address this summer for downtown Kansas City.

To the Hoffmans, moving from a mansion to a River Market condo and ditching their pool for a skyline view just made sense: They were traveling more and their two children were grown, so they didn’t need a big house. And they always liked urban life.

“We love the urban streetscape in this area, to walk to the City Market, to be five minutes away if we want to go to the Folly Theater or the Music Hall or the new performing arts center,” says John Hoffman, a longtime arts benefactor and brokerage executive.

“We feel we can live here and incorporate the neighborhood into our lifestyle, as if we were in a small community.”

Kansas City is seeing hundreds more people move into high-ceiling, exposed-brick lofts downtown, one spark of life in an otherwise bleak business district. But downtown needs thousands more residents.

Our downtown stretching from the River Market past Crown Center has about 6,300 residents. Vibrant downtowns across the country studied by The Kansas City Star have at least 10,000, and Kansas City Consensus, a citizens public policy group, has called for even more – doubling downtown’s population in a decade.

If that could happen, the payoff could be huge.

For starters, market research data show downtown residents spend a lot of their money on restaurants, bars and entertainment. So more downtowners would woo more night life. They would bring back some retailers. They would fill the streets, either walking or jogging or driving.

All this would help downtown feel safer, make it a better place to work and buff up the metropolitan area’s image to the outside world. It might even put a sock in those Cowtown jokes.

“Adding residents downtown is probably the only way to save downtown,” says Kansas City Auditor Mark Funkhouser, who analyzes the city’s health. “If that doesn’t happen, nothing else will work.”

While reviving downtown will take a combination of changes, from more attractions to cleaner streets, housing is the foundation for everything that follows. It’s the thrust of a downtown vision plan, called the Sasaki Plan, adopted by the Civic Council of top local executives. That’s because across the country, there’s a revolution going on in big-city downtowns, and housing is leading it.

It’s given Minneapolis’ downtown liveliness. It’s helped erase downtown Indianapolis’ “Naptown” image. It’s brought downtown Denver back from the dead.

The Star visited Denver and saw firsthand the downtown residents crowding the sidewalks, filling a coffee shop, walking into a Niketown, climbing stairs into loft buildings, coming out of a drug store on the corner.

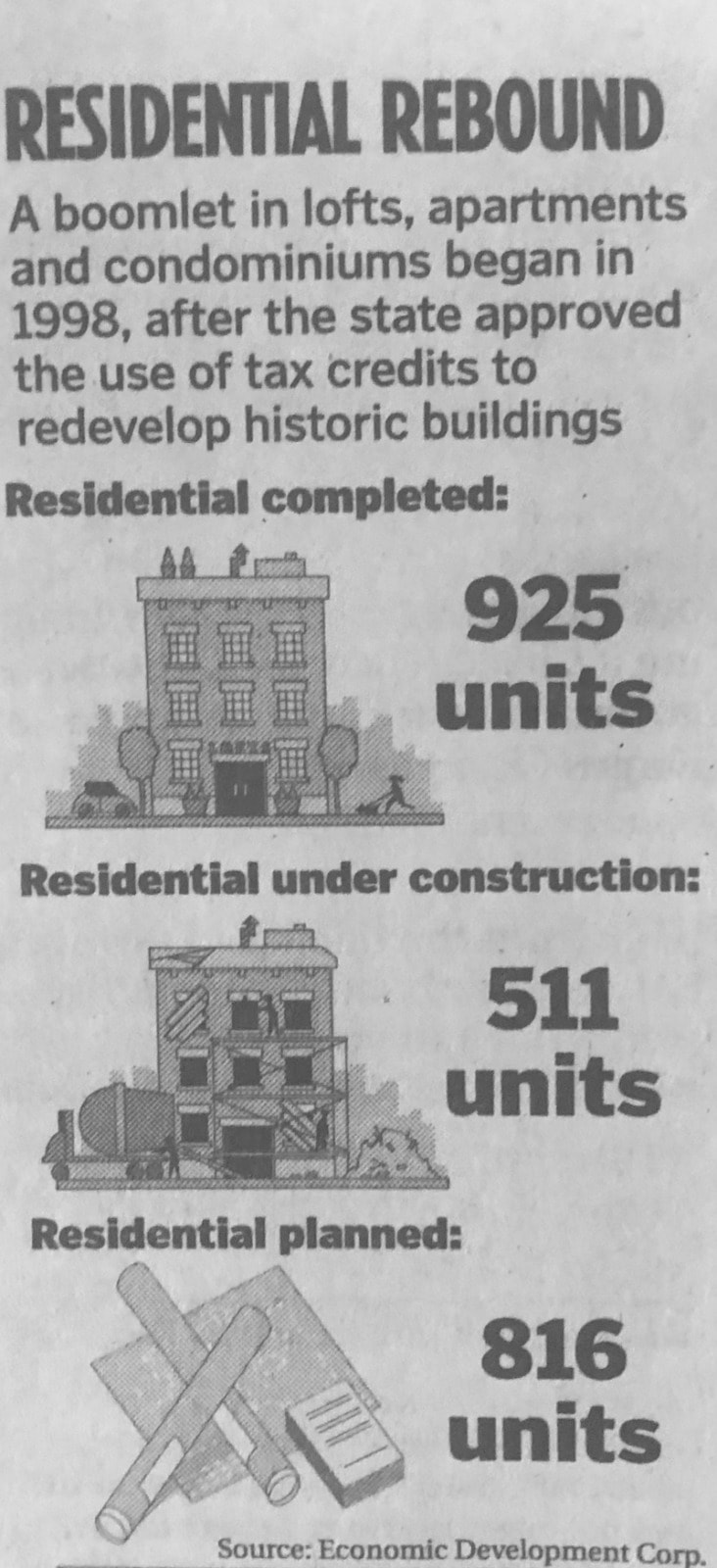

(Graphic from “Mending Our Broken Hearts” series courtesy of The Kansas City Star)

A decade ago, you could fire the proverbial cannon through downtown Denver after work hours and not hit a soul. Today, before you could wheel your artillery into position, you’d likely knock over a dozen lattes at sidewalk cafes and be run over by a free shuttle bus.

“What’s so important about downtown housing,” says Dana Crawford, a pioneering developer there, “is it makes everything else healthier.”

Kansas City is at a point Denver was at a decade ago, in the eyes of developers familiar with both cities. Kansas City’s downtown population has started growing again after a half-century decline. With vacant buildings being converted in the River Market and in the Crossroads, parts of downtown are becoming hip enclaves with eclectic mixes of bohemians and bankers, 20-somethings and retirees.

Now, surveys done for the Downtown Council business association and The Star indicate thousands more people would consider living in a revitalized downtown. If Kansas City would just build on the momentum already there, downtown could have more scenes like this:

A lovely summer evening. The front steps of a Quality Hill apartment building. Three women – Anna Sik, Michelle Keller and Julia Austin – sitting, eating, drinking and commiserating.

“If each of us have a bad day, I’ll call up and say it’s time for our porch drink,” says Keller, who met Austin at the lobby mailbox. The two later met Sik, an immigrant from the Ukraine. “Julia brings the drink, spiked lemonade, and I bring snacks. We like to people watch.”

Demand, then supply

Cities have spent the last generation taking a big-bang approach to downtowns: build a galleria mall or an entertainment district or a sports stadium, then hope people show up. And that did happen – but only on occasion and only for a few hours.

Housing, in contrast, keeps people downtown around the clock, every day.

“You have to start with the people, not with the facilities,” says John McIlwain at the Urban Land Institute in Washington. “As you start to get a critical mass of people, the commerce comes in on its own.”

One reason that’s true for downtowns is because the people living there make more money than average and spend more of it on things downtowns cater to.

The average salary in metropolitan Kansas City is around $35,000. But a survey done by the Downtown Council found that downtown residents earn an average of $55,800. These aren’t elites like the mayor or the county executive or top CEOs, because none of them live downtown, but graphic designers, sales reps and the like – often young and single – who work more in professions and less in the service industry.

A bunch of their extra spending is going toward culture and night life.

A River Market resident spends 67 percent more than the average metropolitan resident on restaurant meals, according to Claritas market research data. A Garment District dweller spends 51 percent more at bars than a typical metropolitan area resident. And a Crown Center inhabitant spends almost twice as much on theater and museum admissions than the area average.

John Leisenring is typical of these downtown residents: He eats, shops, bikes, goes to basketball games and attends concerts there.

“I’ve lived in Kansas City for 30 years, and there were lots of attempts to bring downtown back by putting in restaurants and shops and entertainment, none of which worked in my view,” says the River Market resident. “But this is working. There’s a mass of people living here who have some money and are interested in those kinds of amenities.”

It’s a case of increasing the demand side of supply and demand. And for downtowns, that’s leading to uniquely urban neighborhoods – with things like music clubs instead of chain restaurants and specialized boutiques instead of big-box stores.

For a long time, however, downtowns focused on retail first. Denver, for instance, built the 16th Street pedestrian mall in the early 1980s, then produced a downtown plan with a shopping center as its centerpiece. A new mayor shifted gears, however. The shopping center was shelved. Instead, housing was tapped as downtown’s priority.

So the city government opened a downtown housing office and offered financing. Then conversions of empty office buildings and warehouses into lofts took off. As that was happening, the city added things to do downtown by locating the Coors Field baseball stadium and a performing arts center there.

In the 1990s, Denver’s downtown population jumped by almost a third, passing the 10,000 threshold. The number of downtown restaurants grew by a quarter in the last half of the decade. And, lo and behold, specialized retailers popped up too, stores like Barnes & Noble and Virgin Records.

“It’s phenomenal,” says Anne Warhover, who ran Denver’s downtown housing office. “You can come on a Sunday morning and see people strolling the 16th Street Mall, going to breakfast, getting the paper. It’s not New York City, but it’s 110 percent different from 10 years ago.”

Garrett’s Corner Market at 201 Main St. was part of downtown’s recent increase in eating and drinking places. (Photo from “Downtown KC: Mending Our Broken Heart” series courtesy The Kansas City Star)

Kansas City’s downtown is beginning to show similar signs of life. The number of eating and drinking establishments increased 14 percent in the last half of the 1990s. One of them was Garrett’s Corner Market.

It opened in the River Market as a corner grocer with five shelves of food. Then it expanded into a deli. This year it expanded again, creating a new space adorned with sleek stainless steel shelves, railings and chairs.

One recent Saturday, the line to the deli counter stretched out the door, where people with exposed midriffs stood next to people with graying temples. The market’s growth and the neighborhood’s growth: “They’re parallel,” to Garrett’s owner Tucker Graves.

Kansas City’s downtown residential base, however, is still a ways away from attracting much of a retail market, even for neighborhood-type services. The number of liquor, drug, laundry and beauty shops in our downtown fell 13 percent in the last half of the 1990s, continuing a decline stretching back decades.

“Without a doubt, it’s very difficult still to operate a service business on an 8-to-5 weekday market,” says Chris Sally, downtown development manager for the city’s Economic Development Corp. “We’re still a little short on the population.”

Urban trends

Indeed, our downtown population is somewhat small and scattered compared with 16 similarly sized, inland American cities – places considered our peers like Denver, Indianapolis, Louisville, Ky., and Oklahoma City.

While our downtown is above average in geographic size, it’s 14 percent below average in population and 39 percent below average in population density.

Now a convergence of societal trends presents a rare window of opportunity for all cities – but particularly laggards such as Kansas City – to use housing as the cornerstone of a downtown revival.

Urban and suburban landscapes are changing. In suburbs, traffic congestion has worsened, making some people want to live close in and close to work. In cities, the streets have become much safer, diminishing one of the barriers to urban living.

Violent crime in downtown Kansas City has dropped almost by half in the past decade. Of course, even when accounting for residents and office workers, downtown still has a few more murders than similar-sized suburbs. But downtown is actually a safer haven against more common crimes.

According to The Star’s analysis of crime records, someone was more likely to be assaulted or have something stolen in Independence or Overland Park than in downtown Kansas City last year.

“It’s not necessarily surprising, because you have a lot of office workers who are working inside, in their offices, and the business district is not a place where a lot of criminals live,” says David McDowall, co-director of the Violence Research Group at the University of Albany in New York.