Mending Our Broken Heart: Diversions Needed for Downtown to Thrive (Part 2)

Published October 3rd, 2022 at 11:30 AM

“Downtown KC: Mending Our Broken Heart,” was a groundbreaking series originally published by The Kansas City Star 20 years ago this month.

It was written by former staffers Jeffrey Spivak, Kevin Collison and Steve Paul, with photographs by Rich Suggs. It was edited by former deputy national editor Keith Chrostowski.

CityScene KC thanks The Kansas City Star and Mike Fannin, its president and editor, for granting permission to republish this report.

While The Star retained the text of “Mending Our Broken Heart,” the original photos and graphics were unavailable. Photos of that missing material from a reprint of the series were used as much as possible.

The prospect of Julia Irene Kauffman’s planned performing arts center has loomed over downtown in recent years like an Emerald City in the distance.

It is scheduled to open in 2007 with two new halls for the Kansas City Symphony, the Kansas City Ballet and the Lyric Opera. One of the halls would be large enough to accommodate the largest Broadway touring productions, such as “The Producers,” which is stopping in several of Kansas City’s peers this fall but not here.

The center’s glassy, bowl-shaped design for 16th Street and Broadway will be a landmark addition to the skyline.

“This will rival the Sydney Opera House,” lawyer and civic leader Myron Sildon recently told an arts breakfast gathering. “This will be something incredible.”

Most importantly, the $304 million center is expected to draw 600,000 audience members – nearly 400,000 more than now attend symphony, dance, shows and other performances in such venues as the Music Hall and Lyric Theatre. And plans call for the center to be used almost every day.

As a hub, it will anchor a cultural district encompassing several old stage theaters in the freeway loop, some two dozen galleries in the Crossroads, plus theaters in Union Station and Crown Center – further bolstering this region’s No. 6 national ranking in Money magazine’s metropolitan arts index, based on the number of museums and arts programs.

Across the country, such cultural districts are seen as ways for downtowns to reinvent themselves.

Cincinnati finished a performing arts center and is building a contemporary arts center. Milwaukee expanded its downtown art museum and a performing arts center. Nashville added a Country Music Hall of Fame and is renovating its performing arts center.

“Arts centers can play a role in revitalizing areas by providing steady activity that encourages people to visit downtown,” according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Va.

Consider Pittsburgh’s Cultural District.

Business leaders there formed a Pittsburgh Cultural Trust to oversee redevelopment within a 14-square-block area. The trust has built and renovated theaters, added sculpture parks and a landscaped river walk, and created a national historic district to help reuse 51 buildings.

Since that started in the mid-1980s, the number of theater and gallery patrons has doubled to about 1 million a year.

Some nights a concert and a play are going on and a baseball game is under way across the river. At 10:30 p.m. the streets become electric with patrons spilling out onto the sidewalks. Some head home, of course, but others drop into the Bossa Nova lounge or to late-night dance clubs in the Strip entertainment district. The Cultural District sends out ripples all around it.

“Without question,” says Kevin McMahon, president of the cultural trust, “all the brand-new development on the north side – two new stadiums, a couple of corporate headquarters, including Alcoa – would probably not have occurred if the Cultural District hadn’t undergone the renaissance the way it had.”

The Webster House opened as a school in 1885 and was renovated by the Helzberg family to become a restaurant and antique shop in 2002. It’s now the home of the Kansas City Symphony.

In Kansas City, the likely arrival of a performing arts center already is creating economic ripples. Philanthropist Shirley Helzberg renovated the bell tower-topped Webster House School into a fashionable antique shop and restaurant. It’s next to the arts center’s site and also along a proposed retail and restaurant row on 17th Street.

“We wanted to do something that would be attractive and bring people to the neighborhood who hadn’t been there for many years,” Helzberg says, “so they would know how viable the area was.” Expanding Bartle?

Across the south freeway loop from the performing arts center could be two other parts of the entertainment equation for downtown – Bartle’s expansion and an arena.

Each project comes with questions about its individual merits. Together, though, they deserve consideration based on a bigger picture: what they would do for downtown.

Bartle’s expansion is on the city’s November election ballot, which seeks higher hotel and restaurant taxes for about $74 million in improvements. These range from technological upgrades to building another ballroom, which would span the freeway and face the arts center with a public plaza.

Kansas City has been down this road before. Bartle’s size was doubled a decade ago. But no restaurants or bars opened nearby except those in hotels, and it took years for convention traffic to significantly surpass pre-expansion levels.

So why expand again?

Because attendance figures show that Bartle is the single largest traffic generator downtown among public facilities, and expense account-toting tourists are a ready-made market for downtown entertainment.

Conventions are big business in Kansas City, attracted to our central location and relatively low costs. The 770,000 attendees passing through last year spent an average of $555 – which translates into a $428 million economic effect. Compared with our 16 peer cities, we ranked No. 2 in the number of convention meetings last year and in attendance.

The Bartle Hall ballroom addition opened in ?

But we’re losing potential business – because of Bartle’s condition and the condition of downtown.

For instance, the Shriners rejected Kansas City for their 2006 convention. One reason: “Not having a ballroom large enough to accommodate our group,” Shriner Gary Dunwoody of Little Rock, Ark., wrote Kansas City’s convention bureau.

Another reason: “When attendees go out the front door of the Marriott (hotel), there is absolutely nothing in the immediate area. Knowing our delegates, this is most definitely a negative.”

Bartle’s expansion, then, can’t be done in isolation. Neither can another project: a new arena.

An arena?

Kemper Arena once housed professional basketball and hockey teams, was a host of NCAA college basketball Final Fours and permanently had the Big 12 basketball tournament. Now all those are gone.

So the Greater Kansas City Sports Commission is wrapping up a study that, according to commission officials, will recommend a $200 million, publicly funded arena with the same 18,000-19,000 seats as Kemper and roughly the same number of yearly events.

Why, with no prospects of winning back the Big 12 or a big-time sports team, should the city consider this?

Because, according to arena backers, Kemper doesn’t measure up to today’s standards for entertainment venues – not just because of narrow concourses, cramped seats and lack of rest rooms, but because of where it is, with little going on outside it.

As a result, Kemper – like Bartle Hall – is losing some big-name, high-profile acts that are bypassing the city.

When the Sports Commission recently failed to land the NCAA hockey tournament and another women’s basketball Final Four, the reason was: “You don’t have the fan amenities,” in the words of one local official. Translation: Kemper’s environs are no fun.

“Its location is probably one of its most damaging features in our ability to attract big events,” says Ron Labinski, retired founder of HOK Sports Facilities Group who is a co-chairman of the sports commission’s arena study.

Replacing Kemper would generate about 700,000 attendees a year to a spot downtown where there’s more fun nearby.

That spot could be at 14th Street and Grand Boulevard. At least that’s the site favored by the business community’s Sasaki plan. It would be a short walk from Bartle and the performing arts center.

Together, the three projects offer an opportunity to heal downtown’s biggest wound – the one left by the failed Power & Light District. That’s because the sum of downtown’s new entertainment equation could be greater than its parts.

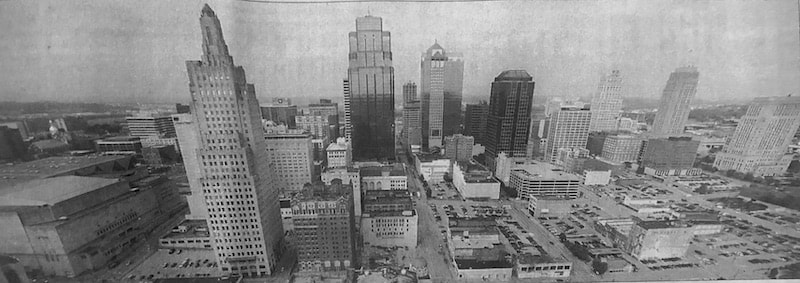

Downtown’s biggest wound–the one left by the failed Power & Light District (in the lower right of this photography)–could be saved by three projects: the performing arts center, Bartle Hall expansion and the new arena. (Photo from “Downtown KC: Mending Our Broken Heart” series courtesy of The Kansas City Star.

One of Kansas City’s new downtown leaders, Andi Udris of the city’s Economic Development Corp. predicts the three projects would create the demand for some sort of “son of” Power & Light, a cluster of themed bars and eateries.

These could even help fill the Power & Light’s vacant land, centered at 13th and Main streets, because it’s right in the middle of the three projects.

The need for such hot spots remains – Kansas City is one of only a handful of its peer cities without a downtown nightclub district.

“It would be so logical to tie all these together,” Udris says.

Progression of change

Now, how do we pull this off, this $700 million in new and expanded downtown development?

A consensus is emerging in civic and political circles for what Mayor Barnes calls sequencing new projects. Bartle is already on the city’s November ballot. But before downtown’s two other big projects possibly get their turn, they have obstacles to overcome.

The performing arts center will require a record local private fund-raising campaign that may exceed $250 million. It already has a record lead commitment: $105 million from the Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation. It also expects some public funding, such as part of another areawide bistate tax package.

As for an arena, it doesn’t even top the civic community’s sports wish list yet – modernizing Kauffman Stadium for the Royals does. So many civic leaders view an arena vote as a couple of years away.

Even then, it will be a tough sell: In The Star’s opinion poll on downtown, more than two-thirds of area respondents felt downtown did not need a new arena. Plus, a smaller venue proposed in Olathe could complicate Kansas City’s effort.

In the meantime, the experiences of other cities suggest that Kansas City’s government should come up with plans to make the most of the performing arts center, the Bartle expansion and a downtown arena.

Former Mayor Barnes enjoys unveiling of sculpture honoring her, “Woman Walking Tall,” at the ballroom named after her at the Convention Center.

Those experiences show that such structures can’t be plopped down in some empty spaces surrounded by parking lots. They have to be integrated into an active, urban environment that makes the walk to and from the facilities part of the draw.

To do this, incentives can be offered for small businesses to locate near the facilities. The Greater Kansas City Community Foundation expects to help with this by offering a small subsidy program whose target is homegrown restaurants and retail downtown.

Prospective restaurateurs would welcome that.

“If you could get some assistance, something that gives you incentive, plus support on the marketing side so you know crowds will come, I would definitely consider downtown,” says James Taylor Jr., who has created three successful restaurants in Kansas City, but none downtown.

The Sasaki plan recommended such a downtown marketing organization. But it has not been formed yet. It would not just promote downtown but also sponsor festivals – something else that could pump some life into downtown. Some of Kansas City’s peer cities offer free concerts on weekdays, plus ethnic festivals or other fun events – like classic films shown outside at dusk – on weekends.

“We’re going to do events downtown,” says Bill Dietrich, new president of the Downtown Council, which would partner with a marketing agency. “We have to. They’re part of what makes downtowns exciting.”

Finally, downtown has one other destination opportunity: Union Station. It was restored, but its science museum and theaters have not drawn enough visitors.

Station officials realize more needs to be going on there. They are talking about teaming up with the Cosmosphere space center in Hutchinson, Kan., exhibiting Smithsonian Institution artifacts and creating a Kansas City history museum. The goal is drawing 300,000 more visitors. To help with this, officials are proposing a $100 million endowment.

Ultimately, getting all these things done can benefit the entire metropolitan region.

In today’s economy, the fortunes of regions are increasingly driven by the tastes of one group of people, dubbed “talent workers.”

These creative people, ranging from software developers to graphic designers, are valuable to industries as varied as telecommunications and life sciences. And they choose to live in lively cities – cities with urban night life like music clubs and cultural attractions like the symphony, according to surveys done by Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Making downtown an entertainment destination again can make a difference in attracting and keeping these talent workers. Listen to Matt Miquelson, a Web site developer:

“I’ve heard people who were moving away say they’re simply bored here, and I’ve thought about moving several times, too,” he says. “If there was a thriving downtown entertainment scene, that would definitely make a difference to me.

“It would add to the whole package of the community.”

THE POLL

Should downtown still be an entertainment center for the city or metropolitan area?

Yes 92% .

No 8%

WHAT DOES DOWNTOWN NEED?

1. A performing arts center?

Yes 67%

No 33%

2. A new sports arena?

Yes 31%

No 69%

When looking at the poll results in total, the margin of error, at a 96 percent confidence level, is plus or minus 4 percentage points. That means that if this study had been repeated under the same circumstances 100 times, the results for each question would not vary by more than 4 percentage points in 96 of the 100 times the study was conducted.