Climate Change Highlights Value of 19th Century Plan for ‘A City Within a Park’ What’s Old is New Again

Published May 18th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: The bur oak in the foreground is one of several trees the Heartland Tree Alliance has planted at Seven Oaks Park in Kansas City, Missouri. Mature trees in the park make it a rare cool spot in the neighborhood, according to heat data collected last year by the University of Missouri-Kansas City. (Mike Sherry | Flatland)More than a century ago, in the 1890s, Kansas City’s civic leaders hired landscape architect George Kessler to transform their filthy boomtown into an urban oasis of parks and boulevards. The idea was to create a “city within a park.”

Today, civic, government and nonprofit leaders are once again focused on the city’s greenery. But this time they are looking to trees to combat the causes and effects of climate change, which is partly due to the paved streets that Kessler and his benefactors coveted.

Trees figure prominently in several local and regional reports issued in the past few years that suggest a number of actions to curb and adapt to climate change. Kansas City’s Urban Forest Master Plan, issued in 2018, focuses exclusively on the tree canopy.

The plan calculated that, at approximately 31%, the city’s overall tree canopy was only about half of what it could be based upon the available acreage. But with approximately 60% of the city’s trees rated to be in fair or worse condition, the report said, the tree canopy could drop significantly in the coming decades. The plan set a goal of 35% canopy coverage, urging a plan to replace the “significant amount of canopy” that would be lost within the next five to 10 years.

“Essentially,” the report said, “it is time to rebuild Kansas City’s urban forest and re-establish The City Within a Park.”

The Regional Climate Action Plan, issued last year by the Mid-America Regional Council (MARC) and environmental nonprofit Climate Action KC, is among the recent reports that have noted the benefits of trees. They help mitigate the effects of increased temperatures associated with climate change and capture the greenhouse gasses that trap heat in the atmosphere.

“Heat islands” are of particular concern for urban areas like Kansas City, where areas of asphalt and buildings can be as much as 7 degrees hotter than outer lying areas during the day, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Increasing tree canopy coverage and other types of green space helps reduce urban heat islands, provides healthy spaces for residents to enjoy, cleans the air, and provides wildlife habitat,” the city noted in a draft Climate Protection & Resiliency Plan it issued in March.

The City Council could adopt the final version of the climate and resiliency plan as early as next month. The city received more than 700 public comments on the draft plan.

Trees Can Counter Heat Islands

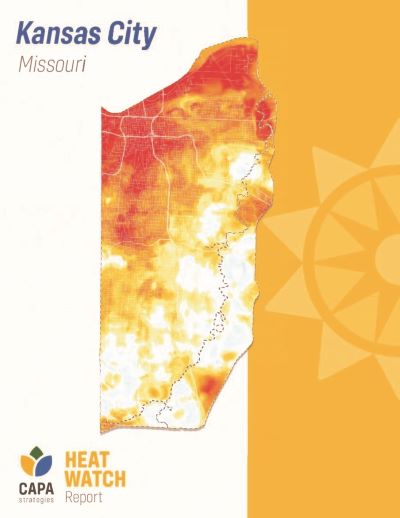

The University of Missouri-Kansas City coordinated a heat mapping exercise last summer, with Assistant Professor Fengpeng Sun leading the federally funded effort.

A high-level overview of temperatures recorded by volunteer drivers, who drove routes through a portion of Kansas City in the morning, afternoon, and evening, show hot and cool temperatures recorded in all parts of the city covered by the study. The very far south portion of the city generally had more cooler routes than elsewhere.

Given the time and expense, Sun said it could be next year before he is able to provide a detailed analysis of the results. He hopes the data can provide real-world validation to climate modeling.

Digital mapping of Sun’s data by local arborist Sarah Crowder has helped pinpoint the cooling benefits of oases like Seven Oaks Park, located at 39th Street and Kensington Avenue on Kansas City’s east side.

As senior program manager with Bridging The Gap, an environmental nonprofit, Crowder oversees the Heartland Tree Alliance. Saplings in Seven Oaks Park are among the approximately 18,000 trees alliance volunteers have planted since 2005.

Sugar maples, pin oaks, and white ashes are the predominant species among the trees on public property within Kansas City, according to the city’s forest master plan. Alliance plantings in Seven Oaks Park include a Japanese pagoda, an American linden, a red maple and three oak varieties.

The value of trees can be measured in dollars and cents.

A MARC analysis found that shade trees — priced out at about $100 apiece — provide regional annual energy cost savings of approximately $21 million. And the regional climate action plan said shade trees reduce the amount of energy needed to heat or cool homes by as much as 25%

The city also calculated cost savings attributable to trees, saying in the forest master plan that they provide more than $28 million annually in municipal services, such as stormwater management, air pollution control and energy reduction.

The plan also noted several other ways trees can benefit a community, citing research that they provide a “narrowing speed control measure” on city streets and can even calm adults and teens who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The latter is included in a 2006 publication laying out 22 benefits of urban street trees.

Some effects of climate change can fall particularly hard on lower-income communities. Increased heating and cooling costs, for instance, can be harder to absorb in households of lesser means.

But in comparing the urban tree canopy in Kansas City to census data, the forest master plan found “no significant difference in canopy between areas with differences in median household income or by population density.” In fact, areas with higher proportions of high school and associate degrees had more tree canopy than areas with more advanced degrees (bachelors and beyond).

In ranking nearly 250 city neighborhoods by their percentage of tree canopy, the forest master plan placed Riverview in the Northland first with coverage of more than two-thirds. The Crossroads Arts District near downtown was at the opposite end of the spectrum with tree cover barely exceeding 1%.

Riverview benefits from a healthy dose of public greenspace within its borders, including a north-south greenway and North Hills Park. Parking meters, by contrast, are the defining feature of the Crossroads landscape.

The average citizen intuitively knows the value of trees, said Tom Jacobs, director of MARC”s environmental programs.

“If you drive into a parking lot and you are looking for a place to park,” Jacobs said, “are you going to park in the middle of the sea of asphalt, or if there is a tree with a little bit of shade, are you going to park in the shade of the tree? Everybody parks in the shade of the tree first — everybody does.”

More Than Meets the Eye

But one must be more discerning when evaluating the overall benefit of the tree canopy, Crowder said. The presence of trees can be deceiving when considering the long-term benefits for a neighborhood such as the Historic Northeast.

At present, Crowder said, the trees in that neighborhood are wonderful. “They are big, they are beautiful, they are glorious, and they are providing all kinds of benefits and things, but they are also nearing the end of their life, and there is not a lot of diversity in age.”

Crowder said engaging the public is a key strategy in helping devise strategies to improve the environment and combat climate change. That’s true whether you are planting trees, or as Sun did with the UMKC project, using volunteers to drive around the city collecting heat data.

In her world, Crowder said, generating excitement among residents might be even more important than having a newly planted tree grow and thrive.

“There is a lot more to gauge success than just what the end result is,” she said. “It is getting people involved, getting them talking, having conversations, sharing with their friends and being a little bit of an advocate — ‘Guess what I learned today?’ or ‘I did this cool project.’

“I think that is big — very big.”

Mike Sherry is a former editor and writer for Flatland. He is now a communications consultant for nonprofits and freelance writer.