Cameron Lamb Case Stirs Emotions of Those Who Have Lost Loved Ones in Police Shootings Triggering Hearts

Published December 14th, 2021 at 6:00 AM

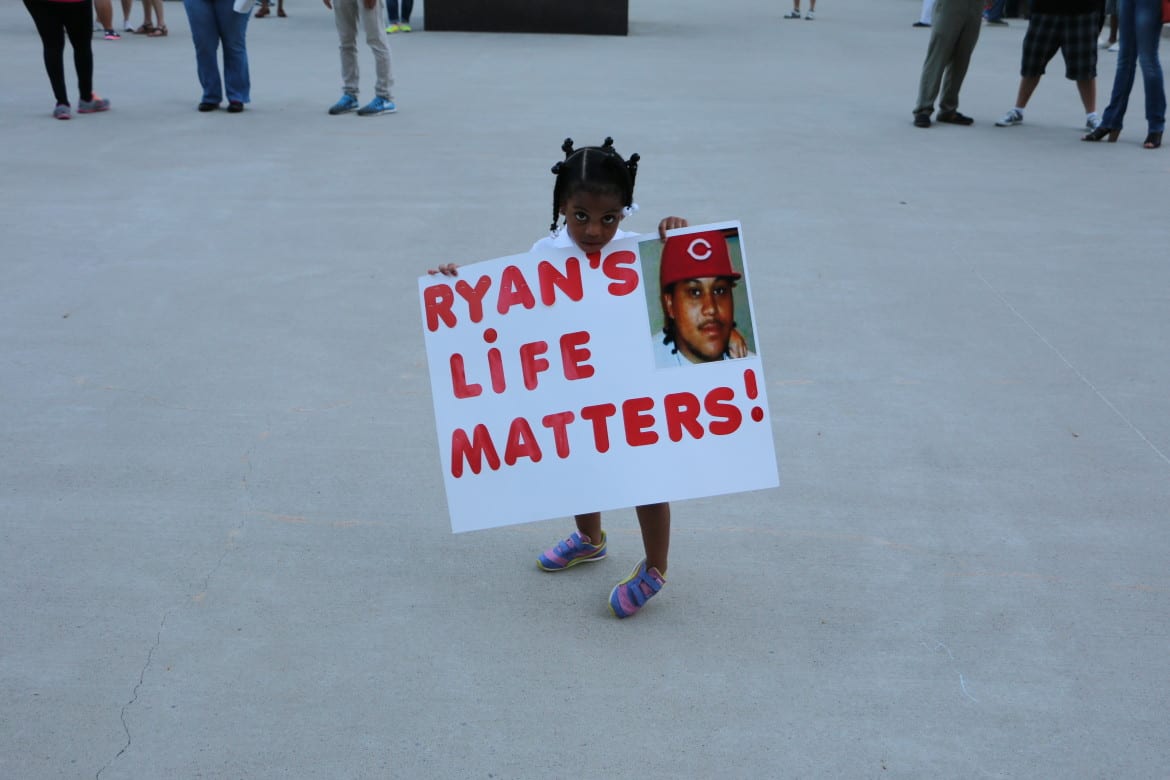

Above image credit: Neriha Stokes, the daughter of Ryan Stokes, participated in a vigil for her late father. Ryan Stokes was shot by an Kansas City police officer on July 28, 2013. (John McGrath | Flatland)Never tell a mother that her son didn’t matter.

Don’t do it with scant news coverage of their shooting death in an “altercation” with police. Don’t allow passive community acceptance of a law enforcement narrative – the one that describes a gun being brandished, or that the deceased had done something questionable in the moments leading up to their death.

A mother will press for a full accounting.

Narene Stokes has diligently been on that maternal path for eight years, ever since her only son, 24-year-old Ryan Stokes, was shot and killed by a Kansas City police officer near the Power & Light District on a summer night in 2013.

“It’s been tiring for us. But we can’t give up,” she said. “I’m not giving up.”

On Sunday, she drove across the state of Missouri, hopeful that this week’s legal juncture will bring some measure of solace.

Years ago, she filed a federal wrongful death suit against the Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners and the officer who fired the shots that night, after a grand jury cleared the officer of wrongdoing.

Stokes will join two attorneys at 9 a.m. Tuesday in a St. Louis courtroom as part of “team Ryan” and listen as an appeal is made to a panel of three judges in the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals. Family and friends will watch the proceedings by a livestream.

“We were thinking that we were going to get into court and that we were going to have a trial, but we never did,” Stokes said. “They just kept pushing us back.”

A federal judge ruled last year that the officer had used “reasonable” deadly force when he fired the three shots – with two hitting her son in the back. The officer feared for his life, believed that Stokes had a gun and suspected he was going to ambush other approaching officers, the court found.

But he did not carry a gun, his mother insists and even police records indicate. And the initial reason police responded was because Ryan and his friend, both African Americans, were falsely accused of stealing a cell phone. The charge was made by a drunk white man who’d been partying in the entertainment district, police and court records show.

His mother’s sense of helplessness has recently been somewhat alleviated by the legal victories of other families who have also sued the police, shifts in public attitudes and improved transparency in how such police shootings are investigated.

”We are hopeful that ours will get the same,” she said. “It gives me more hope.”

Other families said the same. But it comes with a Catch-22. Attention to current cases can also retraumatize, stirring dormant emotions.

Timing matters. For some, their loved one’s death preceded Black Lives Matter. The public never chanted their son’s name.

For others, the incident might have been prior to the police outfitting officers with body cameras. Or it happened so long ago that it’s become painful family lore, not a complete story, with grief-stricken relatives aging, or even passed away.

Lora McDonald, executive director of MORE2, Metro Organization for Racial and Economic Equity, said that media coverage of more recent officer-involved shootings led some families to discover that officers they questioned in prior instances have been involved in multiple excessive uses of force.

Black families also saw the attention garnered by white families who have lost loved ones in police shootings and questioned, “Do the white families get better justice?” McDonald said.

“But they’re all dead, and the families are all having the same experience, just differently,” McDonald added.

Amid all the losses, McDonald noted, networks are forming, with some bridging racial, geographic and wealth gaps, which is powerful on many levels. Often, it’s women taking the lead – as mothers, aunts and grandmothers pressing for changes in attitudes and police training and policy, hopeful for some sense of peace for their loss and in many cases, anger.

Sheila Albers also is going to St. Louis and plans to be with Stokes during the appeal. Albers’ 17-year-old son John was fatally shot by a now former Overland Park police officer in 2018.

A list of people who have died by police shootings in Kansas City is being compiled. Dozens of names are on the list.

One of the youngest and the earliest cases is that of Timothy Wilson Jr. He died at the age of 13 on Nov. 9, 1998, shot five times by three Kansas City officers. He led police on a chase and they testified that they believed he had a gun and was going to ram them with the truck he drove. A settlement was eventually reached with his mother, with the police department admitting no guilt.

Ultimately, the scrutiny of virtually every case – whether recent or decades ago – lands here: Did police have other options? Could the now familiar term “de-escalation” have helped? Could better training around mental health issues have made a difference?

Could both the officer and the citizen have walked away, unharmed?

Hearts and Triggers

More than a half hour into the meeting, Kansas City Councilwoman Melissa Robinson interrupts the drone of the conversation, trying to shift the focus.

The Dec. 9 meeting was the first time the council had gathered to meet with Chief of Police Rick Smith and the Board of Police Commissioners at police headquarters to comb through next year’s police budget.

The room is packed. Law enforcement fills nearly every chair. Media circle the perimeters of the large board room.

“I’m very anxious to hear from you,” Robinson says to police board President Mark Tolbert.

Before diving into the details, line-by-line discussions of the budget and terms of accounting can wait, she said.

First, Robinson wanted to establish a sense of priorities that the council and the police department can agree on.

Later in the meeting, she pressed again, trying to get a consensus on the damage excessive use of force complaints do to public trust. The fact that the department consistently budgets millions of dollars under the amounts ultimately paid out in settlements was the topic at hand.

“Every settlement that comes out, and not in your favor, is a pathway to improvement for the institution,” Robinson said.

The week prior, Robinson, who is also a mother of a son, was the only council member to attend a two-year anniversary gathering for the fatal police shooting of Cameron Lamb.

She stood in a line of people on the grass near the house where, in the back of the property, Lamb was fatally shot by a now former Kansas City detective. In November, Eric DeValkenaere was found guilty of second-degree involuntary manslaughter and armed criminal action.

Offering respect for the Lamb family, who arrived in a caravan and stopped to pray at the site, was the top priority that day. But it also served as a way to use the Lamb case as a reason to keep pressing for changes, especially regarding how Black men are viewed by police and society in general.

Gwen Grant, president and CEO of the Urban League of Greater Kansas City, spoke foremost as a grandmother.

“Our heartstrings are strapped to the triggers of a cop’s gun,” she said.

Ester Holzendorf said she came as a mother, a grandmother and a great grandmother to Black men. She’s been advocating for more respect for Black lives for years. And she intends to keep showing up in courtrooms when police are accused of abuse.

“This is about all of us,” Holzendorf said.

Remembering Dantae Franklin

Most families can’t count on a cavalry of journalists filing Freedom of Information requests seeking stacks of internal police documents after a police fatal shooting. For many, even finding an attorney willing to take the case is too high of a hurdle, particularly when the deceased was believed to have a gun.

That’s the roadblock Nasha Green hit.

Her cousin, Dantae R. Franklin, 24, was shot and killed by Kansas City police on a Sunday afternoon in August 2017.

“There is still so much more to the story than what has been told,” Green, of Leavenworth, said. “The holidays are coming up and it’s just still so hard.”

She chooses these terms to define her mood: “Sad, hurt and frustrated.”

Media accounts at the time, taken from the narrative police provided, reported that her cousin had argued with woman at a gas station around 35th Street and Prospect Avenue.

Police were called. Franklin ran.

One officer chased Franklin on foot. Another followed in the patrol car.

A gun fell out of Franklin’s pants. He reached for it, police accounts said, and pointed it at officers. Police fired, hitting him multiple times in the back of the head and his neck, Green said.

“This is not the way that God had intended my cousin to die,” she said.

One attorney told the family that he knew they didn’t have the money to pursue the case. He added that the fact that Franklin had a gun would almost certainly render his death a justified police shooting.

To Green, those details unfairly shorthand relevant facts.

Yes, Franklin did have the gun, but mostly because he had reconnected with his father’s family members in Kansas City and was spending time there, aware that the area the relatives lived in had higher rates of violence than his home in Leavenworth.

And the woman that he likely argued with, Green said, must have been someone randomly there, maybe someone high on drugs, or homeless. It was not, as many assumed, a girlfriend that he was assaulting.

“I know why he ran,” she said. “He had a gun, but no warrants. You’re a Black man with a gun and two white police officers pull up.”

Green was introduced to Ryan Stokes’ mother and other grieving mothers through networks pushing for Kansas City to regain local control of the police department, instead of the governor-appointed board that now oversees it.

Stokes in November attended a similar program in St. Louis, linking her to families there. She attended the Lamb trial, as she knows Cameron’s mother and wanted to support her.

She’s also connected with an aunt of George Floyd, who was at the memorial site where he died when Stokes visited a nearby mural. The two women stay in touch by Facebook.

The Stokes case initially did not receive heavy media attention. The investigations only came years later. Several enterprising local reporters, notably from Kansas City PBS and KCUR 89.3, did deeper studies, recreating the events of the night and combing through police files, interviewing anyone with a connection.

Stokes continues to be frustrated that her son was viewed as the agitator that night. She believes that he tried to calm the situation before police arrived and pepper-sprayed the group of people arguing. But those circumstances haven’t seemed to matter to the courts, when weighing the officer’s actions.

She has moved away from the house near 51st Street and Chestnut Avenue where she lived with her son. She’s further south now, near the Fred Arbanas Golf Course and the waters of Longview Lake.

But she’s not leaving her son’s case behind.

“I have to have hope and I have to let them know that I’m not going anywhere,” Stokes said. “Not until they put flowers on me.”

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS.