A Place to Sleep: Tenants Seek Homes After Being Displaced Evictions Complicate Search for Housing During Pandemic

Published February 4th, 2021 at 6:00 AM

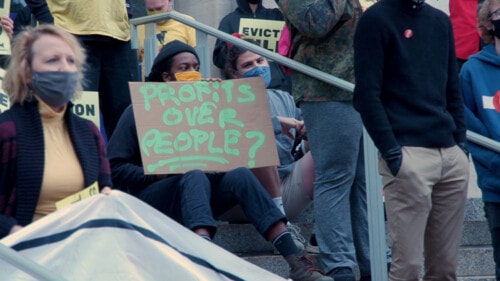

Above image credit: Kieran Vickers, who recently recovered from COVID-19, catches a breath after moving his furniture out of The Alps Apartments. (Catherine Hoffman)After lugging his TV stand down four flights of stairs, Kieran Vickers was winded.

He shouldn’t be. He’s 26 years old and otherwise healthy.

But Vickers is recovering from COVID-19 after contracting it back in December. He and fellow tenant, Alli Reusser, also recently recovered from COVID.

Vickers and Reusser were forced to move after The Alps landlord, Del Hedgepath, gave 60-plus tenants notice to vacate so he could renovate the complex.

Hedgepath doesn’t consider his notice to tenants an eviction.

“Everybody was actually able to move out on time and I’m pretty darn sure no one’s had to move to a shelter, for god’s sake,” Hedgepath said. “For the most part, folks found new apartments, new housing.”

Some Alps tenants even transferred to properties he owns, he added.

Not Vickers and Reusser, though. Both of them found new apartments about one month after getting the notice.

“(The new apartment staff) had heard news about what was going on and they were like, ‘Oh you must be from the Alps’,” Vickers said.

Vickers’ new apartment costs $50 more per month, increasing his rent to $710.

Reusser’s new complex, which is run by MAC Properties, waived application fees, nixed the deposit and gave her a $200 credit toward the first month’s rent. Her one-bedroom at The Alps cost $665 per month. Now, she pays the same per month for a studio apartment.

Others, like Anthony Stinson, aren’t so lucky. Stinson, who is a single father of a 2-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter, has been living in an Independence hotel since he was booted out of a different apartment in Kansas City the first week of January.

“I’m a single parent. I don’t have anyone else to lean on,” he wrote on Instagram.

Since he was evicted, KC Tenants have taken up Stinson’s case. He was able to recoup his belongings, but now faces an uphill battle of finding a place that will accept his application with an eviction on his record.

As of Jan. 27, Stinson has been denied for every single place he applied to, said KC Tenants founder Tara Raghuveer.

That’s been the case for many others in the Kansas City metropolitan area during the pandemic. And evictions, as well as the after-effects, are negatively impacting people of color and folks with children at a higher rate.

Data analyzed by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that renters living with children are twice as likely to be behind on rent. Nationwide, almost 35% of all adults reported (between Jan. 6 – 18) that “it was somewhat or very difficult for their household to cover usual expenses in the past seven days.”

So, how difficult is it to find a new place to live after one has been evicted? And what are local nonprofit centers doing to help?

For one, the aftermath of being physically removed from one’s residence, along with an eviction record, has made it difficult for many to find a safe space. Finding an apartment is already a difficult process, dependent on good credit, background checks and requires enough money saved for a deposit.

“Say you have an eviction on your record from a month ago. No landlord is going to rent to you,” Raghuveer said. “If you have an eviction on your record it’s basically impossible to get anyone to answer your call.

“You probably don’t have any money for a security deposit because you’re in rental debt from your last place (and) you might’ve lost work.”

This, she said, leaves people vulnerable to desperately signing contracts at less-than-desirable housing. That’s due, in part, because there are not enough options.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s most recent report shows that Kansas City’s vacancy rate decreased from 5.9 to 5.6 while rents increased 3% from the year prior. The average rent was $1,037.

Tenant advocates also point to the cost of living, as rates of what’s called affordable housing tap out at $1,100 per month. For context, that’s approximately what mortgage costs for a home in Brookside, according to Zillow estimates.

Consider that the current minimum wage in Missouri is $10.30 per hour, which is $21,424 a year. With that wage, the renter pays about 60% of their earnings toward housing, not counting commuter costs, utilities and other expenses.

While the current ordinance in Kansas City defines “affordable housing” as $1,100 per month, some units are still out of reach. Last week, the Kansas City Council approved an ordinance sponsored by Councilwoman Melissa Robinson, Councilman Brandon Ellington and Mayor Quinton Lucas that prioritizes affordable housing.

The rule is that developers who seek tax breaks must reserve a certain percentage of units for folks based on what they earn and how much they can afford.

This is part of a larger call for action. Local leaders have spoken out about inaccessible and unaffordable places to live in Kansas City for years.

U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver has a keen interest in addressing affordable housing in Kansas City. Cleaver is chair of the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Housing, Community Development, and Insurance.

“Affordable housing is one of the top domestic issues in our country right now,” Cleaver said. “I’m not able to control my emotions when it comes to affordable housing because I have been there. I know what it’s like.”

The former Kansas City mayor and local pastor wrote a letter to the Biden administration, urging better guidance and aid for renters. He felt a need to convey to the new administration that “we’re not dealing with this issue as strongly as we should.”

Cleaver said the original Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s order to temporarily halt evictions during the pandemic has been “spotty at best.” The Biden administration announced in January that the eviction moratorium has been extended “until at least March 2021.”

“Landlords need some assistance and the renters need assistance,” Cleaver said. “At some point, we’re going to be in a really tough situation even after the virus is arrested.”

He is not only advocating for strengthening the eviction moratorium but also “close the loopholes” that allow people to be evicted.

Cleaver also continues to seek a remedy to the affordability crisis.

“I have not had to read about the psychological problems of growing up in an environment like (public housing). I’ve actually experienced it,” he said. “Connected to affordable housing are issues of education and crime.”

Aftershocks

Jacob Wagner, associate professor of urban studies at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, said evictions are a poorly understood factor in neighborhood decline.

“There are other sorts of aftershocks (of an eviction) if you will,” Wagner said, “Not just to the families involved, not just to the landlord that loses income. Not just to… the immediate parties involved, but also to the context of what we might call neighborhood stability, social cohesion.”

If, for example, a neighborhood is part of a cluster of areas in which there are consistent evictions, neighbors may not be as invested because the likelihood of moving is high.

But why aren’t there enough affordable options? Wagner said the public housing system was gutted back in the 1990s.

“Our society walked away from public housing and we basically branded it as a failed experiment,” he said. “We sort of didn’t realize that there is always going to be a need for housing the most vulnerable people in our society.”

Fast forward to 2020. Folks required a safe space to quarantine during the pandemic but were struggling to make ends meet as work hours got cut or they lost jobs. Rent went unpaid. Landlords file eviction notices. And so on.

Wagner said this housing and eviction crisis is “complex” because of an already unstable public housing structure plus unsustainable living wages. Now, it has snowballed into an even larger problem.

“You’re making some really tough choices. Feed your kids or pay your rent, right?” he said. “These are not decisions that we should be forcing Americans to make in this particular moment.”

‘No margin for error’

During the latest round of Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) funding, several local nonprofits secured grants to help them help their community.

Community Services League is a case in point.

The nonprofit is one of a handful of Kansas City agencies that help folks with evictions, landlord-tenant mediation and monetary assistance.

“We just took a look at some of our data yesterday and since January… we have received a total of 75 requests for rental assistance,” said Lynn Rose, CSL’s senior vice president.

She is in charge of allocating money toward resources and managing assistance programs.

The need per household is $2,000. The total needed just to address requests during January is $150,000.

CSL CEO Doug Cowan said none of this – the pandemic and the housing epidemic – happened in a vacuum.

“We’re looking at families that were already struggling, um, barely making it when the pandemic hit and exacerbated their situations,” Cowan said.

When he first started at the CSL in 2010, it was common for the team to be able to write a $200 or $300 check for rent and that covered families’ needs.

“That conversation doesn’t even start now less than $800 or so,” he said. “We’re seeing the marketplace pressure that has really driven up rental rates.”

Online, they’ve received roughly 4,900 applications for utility and rental assistance. He added that it’s important to understand which community members were most vulnerable to the housing crisis.

“What we’re looking at (are) families that were already working on super thin margins, no margins for error,” Cowan said.

That means folks who have recently been evicted face an uphill battle to find new homes. While several options exist for folks experiencing difficulty to pay rent, eviction court continued and people continue to be removed from their homes.

As Flatland previously reported, renters must sign and submit a declaration form to qualify for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Eviction Moratorium. That’s still widely unknown among many struggling renters.

So evictions continue, forcing many into temporary housing or hotels.

So, nonprofit organizations such as CSL and Hope House try to step in.

These are just two of the four centers that received funding back in November to help fill the gap in aid. But sometimes, their funds get tied up in requirement lingo.

Rose said centers like CSL sometimes want to write a check to families in need, but the stipulations given by the federal government are too rigid. Other times, her caseworkers find alternative ways to support folks other than writing a check.

“There’s just not enough money out there… to pay everybody’s bills,” she said.

MaryAnne Metheny, CEO of Hope House, said her center’s been given the flexibility to give the money to those who need it most.

And for the folks she serves, timing is critical. Hope Hope provides services to people who need help to leave an abusive and violent relationship. Domestic violence has also been rising during the pandemic, according to multiple studies.

“Epidemic disease increases the rates of domestic violence,” reads the introduction of a paper in the Journal of Medical Internet Research.

“Affordable housing is the number one obstacle for a domestic violence victim in leaving the relationship,” Metheny added.

So, her center has used the funds they received to provide rental assistance. These days, Hope House has been unable to shelter folks as they did before.

This is one example of how accessible and affordable housing has been a key tenet of stabilizing the housing crisis, according to advocates.

Nonprofit leaders, housing advocates and urban planning researchers all agree on one thing. As it stands now, the needs far outweigh resources available, both in terms of affordable housing and funding that could serve as a stop-gap measure to prevent evictions.

Families hang in the balance as counties cobble together their own interpretations of the eviction moratorium, as CARES Act funding is disbursed to local nonprofits and local leaders work to find a solution.

People who’ve recently been displaced, such as Anthony Stinson and his two children, continue their search for a home during a pandemic and in the dead of winter.

“We’re not just talking about the physical eviction from the home, the risk of COVID. We’re also talking about the mental health costs, the physical health costs,” Raghuveer said. “We’re also talking about the long-term financial implications for that family.”

Catherine Hoffman covers community and culture for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. Cody Boston is a video producer for Kansas City PBS. Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs for Kansas City PBS.