Cargill Executive Says Climate Change Threatens Food Production A Kansas State crowd is urged to take action to protect agriculture supplies

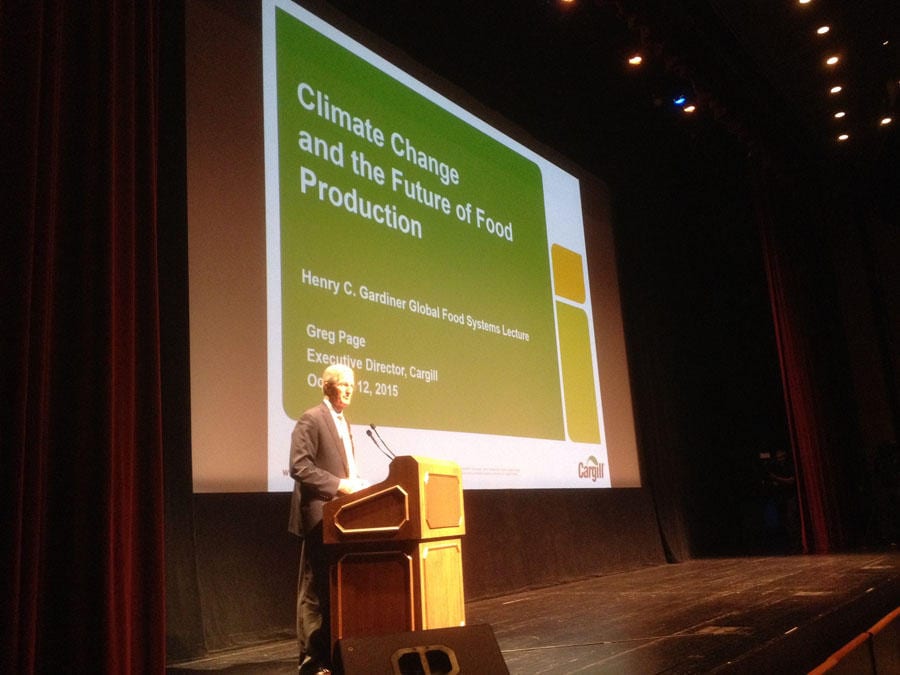

Greg Page, executive director of Cargill, says climate change could lead to drastic reductions in crop production unless farmers adapt to changing conditions. (Photo: Bryan Thompson | Heartland Health Monitor)

Greg Page, executive director of Cargill, says climate change could lead to drastic reductions in crop production unless farmers adapt to changing conditions. (Photo: Bryan Thompson | Heartland Health Monitor)

Published October 17th, 2015 at 7:55 AM

Climate change is real and must be addressed head-on to prevent future food shortages. That’s the message Cargill Executive Director Greg Page delivered Monday night to an audience at Kansas State University in Manhattan.

“Climate change is not a particularly popular subject in much of the heartland,” he said. “But at Cargill, we have come to believe that it is important to have serious conversations about what we can do now to accommodate a range of climate scenarios, and for agriculture to take part in those conversations and in making reasonable preparations.”

In an interview after his talk, Page spoke about the need to err on the side of caution when dealing with a global issue like climate change.

“If this is about flooding the basements of some resort hotels in Florida, that’s one kind of a problem,” he said. “But when it starts to impact the potential for us to feed the 9 billion people that we could be confronting (by 2050), I think it’s important for people at both extremes to realize they don’t know the answer. And the fact we don’t know the answer does not permit us to do nothing.”

Page co-chaired a group of business leaders who looked at the economic risks under various climate change scenarios. Their report, “Risky Business,” concluded that farmers in northern states likely would benefit from a longer growing season. But that would be more than offset by lost production in the southern grain belt.

“U.S. production of corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton could decline by 14 percent by mid-century, and by as much as 42 percent by late-century,” he said.

“U.S. production of corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton could decline by 14 percent by mid-century, and by as much as 42 percent by late-century.” — Greg Page, Executive Director at Cargill

But Page said that scenario doesn’t have to come true if farmers adapt to the changing climate — as he’s confident they will. He noted that adaptation already is happening in his home state of North Dakota. As the climate has warmed there, farmers have been able to take advantage of an average of nine additional frost-free days a year. That longer growing season means they can now grow 30 crops.

“At this stage, the good that’s happened in the top 2 degrees of latitude, basically central North Dakota and up, has not come at the expense of any other place,” Page said. “The most likely scenario in the study that Risky Business published is that we are going to cross that sometime in the next 20 years, the point at which there will be places that will start giving up productivity.”

Page noted that farmers already have technology that might be able to overcome those projected productivity losses.

“The temperatures that are predicted in the ‘Risky Business’ study are actually lower than the temperatures faced by our corn-farming customers in Mato Grosso, Brazil, or in Thailand,” he said. U.S. Midwest farmers could adopt some of their methods when facing possible temperature increases in the coming decades, Page said.

The debate over whether climate change is caused by human activity — like burning fossil fuels — is beside the point, he said.

“If we thought, based on seismology, that we were going to have a period of increased volcanic activity that was going to impact the climate, would we then say that because we didn’t cause it we don’t need to do anything to prepare? What difference does it make, other than on the issue of trying to make people stop certain behaviors? From an agricultural standpoint, we have to prepare ourselves for a different climate than we have today,” Page said.

While Cargill has faced some criticism for addressing climate change, Page said neither he nor the company regrets the decision.

“Should agriculture remain — in the perception of many consumers and many of the world’s biggest packaged-foods companies — deniers and people that are unwilling to engage?” he asked. “Is that a good brand for us, collectively, to carry to consumers, who increasingly, by survey, think to some degree or another this is happening, and that it’s true?”

It’s only natural for Cargill to play a leading role in agriculture’s response to climate change, he said, because the company has operations all over the world.

Page spoke at K-State as part of its Henry C. Gardiner Global Food Systems Lecture Series. He started at Cargill in 1974 as a trainee in its feed division. In 2007 he became CEO of Cargill and later that year also was named chairman. He retired as Cargill’s CEO in 2013 but continues to serve as executive director.

— Bryan Thompson is a reporter for KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.