curiousKC | How Refugee Resettlement Works for Those With Careers One Family’s Search for a Home, and a Job, in Kansas City

Published May 1st, 2023 at 4:26 PM

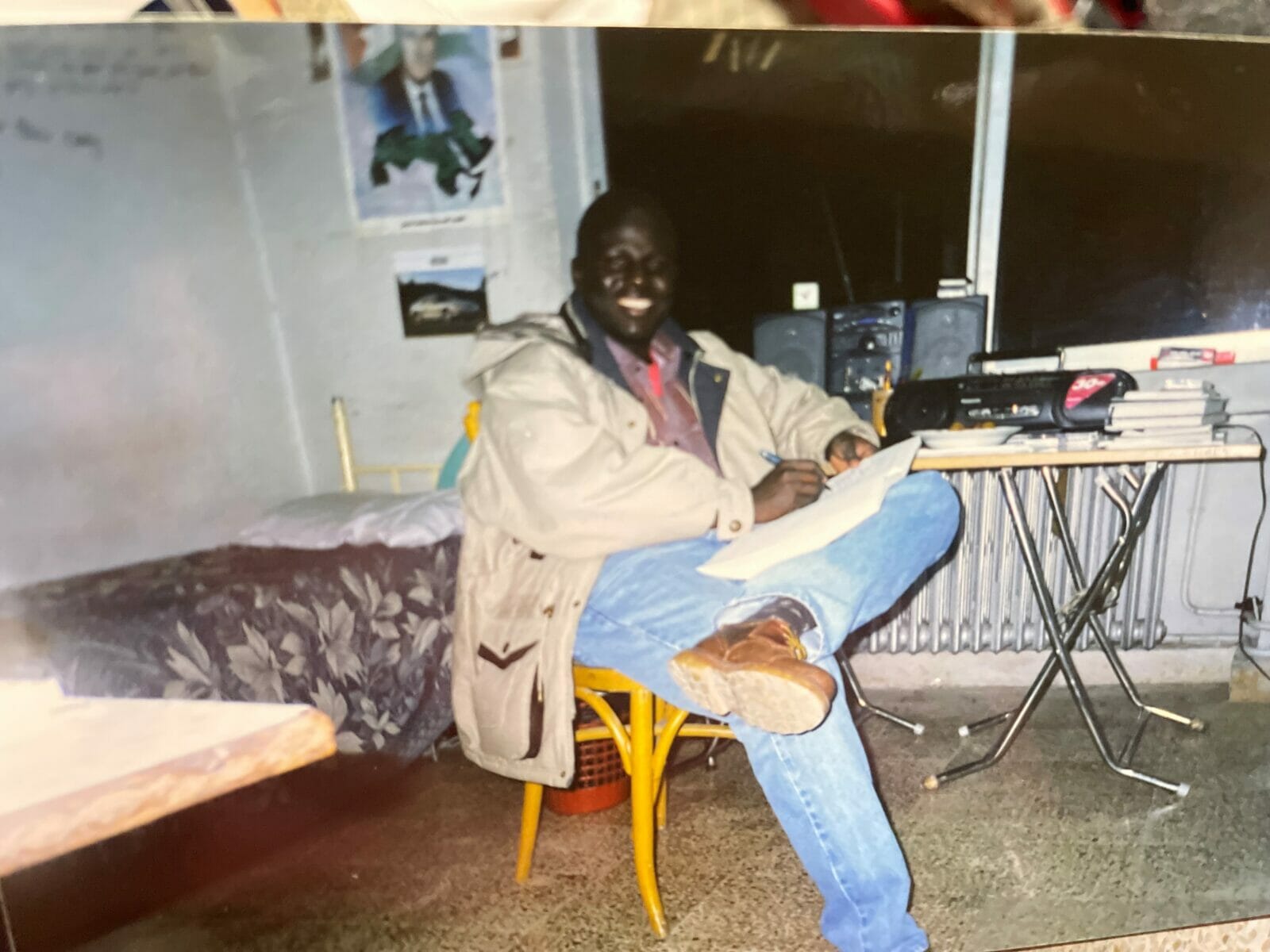

Above image credit: In the 1990s, Denis Kweri was a young 20-something fleeing from the second Sudanese Civil War. From left to right, Jane, their two children, and Denis. The family resides in Kansas City where he says he found a home and hope. Now he wants to pay it forward. (Contributed)It’s taken years. But refugee Denis Kweri and his family have made Kansas City their home.

In the 1990s, Kweri’s family fled for safety during the second Sudanese Civil War. For four years they lived in a refugee camp in Damascus, Syria.

Eventually, the U.S. Department of State approved their application for refugee status. Kweri was in his 20s at the time and recounts the feeling of making a home in a new place. On Sept. 9, 1999, they made their way to their first Midwest home, which was in Chicago.

Neither he nor his siblings spoke English, so they enrolled in English as a Second Language (ESL) courses.

“To know what the American Dream is, you had to go to school,” he said. “We have to go to school. To assimilate to the community, to assimilate to America.”

It wasn’t easy, he says, but worth it. Soon after Kweri graduated from college, his father made an executive decision. They were headed to Kansas City.

“That way we can find a little bit of help and people — a community — to be part of,” he said.

He explained that when the family first arrived in Chicago, they experienced discrimination and feelings of isolation. They wanted to belong, which they found among Kansas City’s 1,200 or so Sudanese.

That boost of support and newfound safety inspired Kweri to become a translator for the U.S. military in Iraq with the Department of Defense for two years. It was his way of giving back, he explained. After two years, he returned to Sudan to get married.

His wife, Jane, was a medical student nearing the end of her residency program. But her credentials would not transfer to the states.

Jane had to start from scratch and enrolled at William Jewel College in Liberty to become a certified nurse.

“I want our community here to know that the refugees are good people,” Kweri said. “They have careers in the country. They have family in the country. They have so (many) things that are well-established. But sometimes when they come here, they have to start from the beginning again.”

These types of stories are what prompted Linda Armstrong, a longtime Kansas City resident, to learn more about how people fleeing their homeland — many who have left careers and families behind — re-establish their lives in the region.

Armstrong submitted this curiousKC question, which prompted Flatland to report this story.

“How closely have refugees from war zones been able to rebuild their lives here after flight? How well has Kansas City enabled them to have a future which matches their pre-war capacity?”

Roughly 500 refugees resettled in Kansas City last year, according to a Jewish Vocational Service (JVS) study.

Nationwide, the number of refugees making their way to the U.S. has been in flux. Data shows that refugee admissions peaked in 1980 at over 200,000 cases.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, Southeast Asian refugees made up the majority because they fled conflict caused by the Vietnam War and Cambodian genocide.

Today, the number of cases hovers at around 20,000, with refugees from Africa forming the largest demographic. However, conflicts in Haiti, Cuba, Afghanistan and Ukraine drove a surge of families seeking refuge.

Clicking through datasets and talking to the providers serving refugees, the picture becomes clearer. Support is not one-size-fits-all, and these unique challenges highlight the cracks in a system working to better serve people’s needs.

Jewish Vocational Services (JVS) is one organization in the metro dedicated to aiding refugees find basic needs such as housing, health, education and career support. In 2021, JVS established a partnership with Rockhurst University to expand their workforce development efforts, according to the organization’s 2021 Annual Report.

Though the influx of folks coming to the U.S. from Afghanistan and Ukraine has dominated headlines in recent years, the differences lie in the level of need and people’s personal goals.

To get to the bottom of our curious Kansas Citian’s question, we sifted through government data, organized one-on-conversations with JVS and interviewed folks in the region about what they want native Kansas Citians to understand about their journey.

‘Super Challenging’

Part of Armstrong’s question focused on professionals with established careers and lives who had to rebuild after settling here.

Providers like Hilary Singer, executive director of the Jewish Vocational Service, have supported many folks with similar stories. Employment is a point of tension.

And recertification is among the most difficult issues refugees with established professions face.

“If somebody has a license, has a degree from their home country, it is often super challenging to have that recognized here,” Singer said, providing an anecdotal example.

A woman who fled the war in Syria with her young son could not find a U.S. employer to accept her pharmacist license from Syria. So, she became a pharmacy technician in the interim and has been working to get the license for the past five years.

“There are so many barriers in the system,” Singer explained. “That is an area where we need additional capacity in the workforce.”

Studies show that even when folks return to school, particularly international medical students, their rate of securing a job in their field is about half as successful. Barriers to employing qualified professionals, such as Jane, throw a wrench into the talent pipeline even in sectors where professionals are needed most.

It represents what scholars call “brain waste,” according to a 2019 paper in the Journal of Graduate Education.

“Medical school graduates cannot fully utilize their skills and education in the workplace despite professional qualifications. This leads to two outcomes — unemployment or underemployment —and individual outcomes including dissatisfaction, demoralization, depression, and lower socioeconomic status, and their associated consequences,” the study found.

ONLY 56% OF INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL GRADUATES GOT A JOB IN THEIR FIRST YEAR COMPARED WITH U.S. GRADUATES, WHO HAD A 94% SUCCESS RATE.

— national Library of Medicine

However, when the crises in Ukraine, Haiti, Cuba and Afghanistan began JVS found itself pulling staff together to find how to best support folks coming to the U.S. for temporary support. The distinction between the refugees JVS has historically helped and those coming to the U.S. temporarily is important.

Singer put it like this:

“The world of immigration statuses has gotten more complex. We’ve seen folks come from other places that are not here on a permanent basis. … Both our Afghan community and our Ukrainian community are technically not refugees.

“They’re refugees little ‘r’ in terms of they fled their country because of persecution, and they need a safe haven here. But they’re not refugees big ‘R’ as far as their immigration status.”

The other group, big “R” refugee as Singer calls it, has to do with folks seeking permanent resettlement to the U.S. Organizations like JVS can only do so much.

For instance, for many young folks in the U.S., internships help expose them to what they like and dislike about a given field. The problem about people who flee and leave behind their well-established careers is learning how their skills align in the U.S. workforce.

There is a need to connect professional refugees with professionals in Kansas City.

“We need the community to come in and help us,” Singer said. “To be that doctor, architect or engineer that’s willing to … extend their hand to somebody who wants to learn the ropes.”

Folks like Kweri’s family.

“We want to find a place that we want to live and share everything together,” he said. “We want to share food, share our culture … share the experience of living together.”

Kweri recognizes where he came from and is grateful for where he is today.

Fleeing the war and creating a safe home in the U.S. gave him hope. And though his partner Jane has had to push past the stresses of assimilation on top of school and rebuilding her professional status, both have made a life they are proud of.

Their story is one that mirrors many in the region.

“After arriving, I knew that this is my home, I’m not going back to live there (in Sudan),” Kweri said.

Success in Kansas City has provided a way for him to give back, he said. He and his wife founded a nonprofit called Kubi for Hope to help people in Uganda and South Sudan. This April, conflicts have again erupted in Sudan, signalizing a third Civil War and prompting more families to flee for safety.

He is reminded of his grandparents and friends who perished because of poor living conditions and a lack of access to clean water.

Their goal with Kubi for Hope is to provide a lifeline for people and give them access to the same opportunities he found when he arrived.

Kweri sees a silver lining in the tragedy.

“Let’s give hope to this country. Let’s give hope to one another.”

Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs and heads up the journalism engagement series, curiousKC, for Kansas City PBS.