Veterans Who Write: Sharing Their Stories, Seeking Peace Giving Voice to Veterans

Published November 11th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Louise Graul, a recent nursing school graduate, arrived in South Vietnam in 1969. In 2015 this photo appeared on the cover of her book -- writing as Lou Eisenbrandt -- “Vietnam Nurse: Mending & Remembering.” (Courtesy | Lou Eisenbrandt).Just before heading overseas Louise Graul, a recent nursing school graduate, received a spiral-bound weekly planner from a friend.

For the next year that 1970 pocket calendar became her war journal. In its pages, she recorded events ranging from the routine to the unnerving.

She documented the arrival of the first bilateral amputee she helped prepare for surgery on her first night in the Receiving and Emergency Ward at the 91st Evacuation Hospital in Chu Lai, South Vietnam.

A few hours later, off duty, the Army nurse unwrapped the birthday cake sent by her mother.

Some 45 years later that evening’s events, briefly noted in the journal, became one of the many episodes retrieved and expanded in her book, “Vietnam Nurse: Mending & Remembering,” published in 2015.

“That evening I was blowing out birthday candles; the next morning, my patient was waking up to a new life, without legs,” she wrote.

The injured soldier had been 19. She had just turned 23.

“It was the juxtaposition of those two events that struck me,” the author – today Lou Eisenbandt of Leawood – said recently about the episode.

“It sort of summed up what the war was all about, it being my first day in the emergency ward and being thrown into everything so quickly.”

With the book’s publication, Eisenbrandt became one of many Kansas City area veterans who have chosen to write – often several decades after the fact – stories about their military experiences. They also have published them, and sometimes even walked onto a stage and presented the stories before a live audience, sometimes standing before projected photographs of their younger, uniformed selves.

Last week members of the Kansas City Veterans Writing Team, a program supported by the Missouri Humanities Council and other entities, read such passages during a “Veteran Reader’s Theater” at the Kansas City Public Library’s Plaza Branch.

On Saturday, Nov. 12, Eisenbrandt – a board member of the Veterans Voices Writing Project, which has published Veterans’ Voices, a magazine of veterans’ prose, poetry and artwork for 70 years – will introduce local author Jason Kander at the organization’s Veterans Day program.

Kander, former Missouri Secretary of State as well as a former U.S. Senate and Kansas City mayoral candidate, and also a former Army intelligence officer, this year published “Invisible Storm: A Soldier’s Memoir of Politics and PTSD.”

Both the writing team and the writing project encourage veterans to take ownership of their experiences through the act of writing them down, in the belief that writing is therapeutic and perhaps one way to heal whatever mental or emotional wounds may still linger.

For Veterans’ Voices, the process began 76 years ago, with organized writing competitions.

Mimeographed Pages, Stapled Together

“Now is the time for all good men to enter the Annual Writing Contest.”

So read the flier distributed by Elizabeth Fontaine, a freelance magazine writer who in 1946 – with the encouragement of her father, a physician – began visiting hospitalized World War II veterans in and around Chicago, convincing them that writing represented effective therapy.

“Here’s your new hobby,” she announced over a hospital public address system during one visit.

Not all veterans medical authorities were on board.

“This idea was not so well accepted in those days immediately following World War II, when Elizabeth Fontaine was convinced that writing is good medicine,” Thomas K. Turnage, Veteran Affairs administrator, wrote upon Fontaine’s 1988 death.

“She persevered in her belief.”

What soon would become known as the Hospitalized Veterans Writing Project ultimately gained the confidence of veterans affairs medical professionals.

The idea spread to Kansas City, where the prose and poetry being composed mostly by men soon began being collected, edited and published by women.

Among them was Margaret Sally Keach.

Keach, like Fontaine, was a member of Theta Sigma Phi, a national women’s journalism honorary society whose members adopted the veterans writing project.

Keach was a published author. In 1939 she had written a memoir about her life in Africa as the wife of a mining engineer. She also served as a community volunteer. During World War II she chaired an American Red Cross campaign aimed at persuading homefront factory workers to donate blood.

In 1951 Keach was among those who visited tuberculosis patients in an Excelsior Springs veterans clinic.

“We were literally shocked at seeing hundreds of these young men lying on cots with white sheets and their faces were almost as white as the sheets,” Keach told The Kansas City Star in 1987.

“They were not enthusiastic at all. I knew they needed something else.”

When Theta Sigma Phi (today known as the Association for Women in Communications) held its 1951 national convention in Kansas City, Keach and other local chapter members resolved to continue the writing contests but also publish veterans’ work in a publication distributed nationally.

“The first issue was 18 mimeographed pages stapled together in 1952 in The Kansas City Kansan newsroom,” said Margaret Clark, Veterans’ Voices editor-in-chief.

Among those present at the creation, beyond Keach, was Lucille Doores, a Kansan state and federal courts reporter today remembered for her response when – while taking copies of the first issue to the post office and finding it closed – scaled a fence while securing the copies, all to make sure those postal workers still on duty took delivery.

Still another magazine co-founder was Gladys Feld Helzberg. The wife of Barnett C. Helzberg, Sr., the jewelry merchant, she was a University of Wisconsin journalism graduate who served as a Kansas City correspondent for Boxoffice, the film industry trade publication.

“She loved writing and reading and Veterans’ Voices was a good combination of that and her own patriotism,” Barnett Helzberg, Jr., said recently of his mother. “She was very proud of the magazine and my dad was, too.”

(The Shirley & Barnett Helzberg Foundation continues to support the magazine today. “Absolutely,” Helzberg said. “Some of the writing is pretty darn good and I think it is a great service.”)

The writing competitions continued, and by 1953 Fontaine had solicited prize money from some of the country’s leading publishing houses.

By then she also had recruited 100 volunteers to serve as “writing aides,” visiting veterans hospitals to directly assist beginning authors. And while the majority of the early contributors were men, Clark remembers noticing work submitted by at least two World War I nurses.

The program enjoyed support from figures representing both military and literary circles.

In 1960 Omar Bradley, former Veterans Administration head and Army general, judged essays for the magazine. In 1968 Robert Penn Warren, who would receive two Pulitzer Prizes for his poetry, considered work submitted in verse.

By the mid-1970s patients in 169 Veterans Administration facilities were receiving copies of Veterans’ Voices.

While achieving literary acclaim such as World War II authors or correspondents Norman Mailer or Martha Gellhorn was never the point, some contributors would gain prominence.

One example was Ron Kovic, a Marine whose combat injuries in South Vietnam left him paralyzed from the chest down. “Born on the Fourth of July,” Kovic’s 1976 memoir, became a 1989 film starring Tom Cruise as Kovic.

Today a hardcover copy of that book sits on a Veterans Voices Writing Project office bookshelf.

Making Movies

“We don’t say, ‘You have to be a writer,’ ” said Sheryl Liddle, the writing project’s board president. “We just say, ‘You should start writing.’ ”

Last year the organization observed its 75th anniversary. Veterans’ Voices, which has been published in the Kansas City area for 70 years, is sent to subscribers three times a year.

This “astonishing feat,” declared one Veterans Affairs official in a 2021 anniversary issue, continues to inspire veterans to “remain focused on their vision, dreams and becoming their best selves.”

Stories Held Within

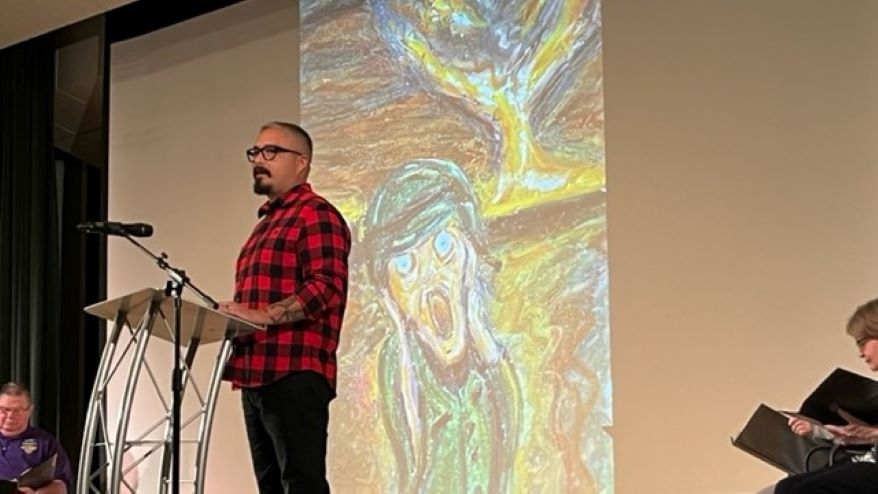

The first veteran to approach the microphone during last week’s “Veteran Reader’s Theater” was Nick Lopez.

Lopez began attending sessions of the Kansas City Veterans Writing Team in 2017, the same year his father died.

His father had served in the U.S. Marine Corps, as had Lopez for eight years, ending in 2013.

He deployed to Iraq in 2008 and 2009, when he served in the military police. His tour included assignments in ordnance disposal as well as providing patrol convoy security and route reconnaissance.

“We were grunts, infantry on wheels,” Lopez said.

“The team I deployed with – we were confident and knew what we were doing. I never had to fire my weapon and never got shot at.”

Nor, Lopez added, has he been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress.

But when he left the Marines, some issues began manifesting,

“When you’re in the Marine Corps you have structure – a mission and purpose – and camaraderie,” Lopez said.

“When I returned to civilian life, I struggled with the transition.”

His challenges increased upon his father’s death.

“In your grief, you kind of self-isolate,” he said.

He soon began attending the writing team workshops. In the past he had written poetry and painted, but had not shared that work with anyone.

The workshops changed that.

“Being able to open up and share your writing with like-minded people gives you the confidence that you are not in this by yourself, that other people have gone through similar experiences,” Lopez said,

“I don’t think I would be where I am today without the writing team.”

Lopez has been published in several publications, Veterans’ Voices among them. Other writing team members have seen their work published in “Proud to Be: Writing By American Warriors,” an anthology series funded by the Missouri Humanities Council and edited by members of the Southeast Missouri State University Press in Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Last week at the Plaza library, writing team members read work that had been developed during the team’s fall workshops.

Today Lopez is the team leader. Members gather once a month at the Kansas City Veterans of Foreign Wars headquarters, where Lopez also serves as youth programs and community service coordinator.

The team also is supported by the Moral Injury Association of America.

The Kansas City-based organization is dedicated to helping spread information as to what constitutes “moral injury,” which the organization’s website defines as “the commission of or witnessing of acts or events that challenge core moral values under conditions of extremity.”

The writing team workshops help veterans perhaps address the inner conflict that such injuries may prompt, George Pettigrew, a Kansas City Navy veteran and writing team member, told the Plaza library audience last week.

Although the writing team does not represent a treatment or wellness center, Pettigrew said, “what we do provide is a safe, secure and trusting environment for veterans or their families to find a release for the stories held within that in numerous cases have not been shared with anyone in as much as 50 years or more.”

Mel Carney of Shawnee, who also presented last week, would reach back about just that far.

Not Much Tranquility

Many Kansas City area veterans who are writing about their military experiences are addressing events that occurred several years – or sometimes several decades – before.

But for some that process has not always resembled Wordsworth’s familiar description of poetry – emotion recollected in tranquility.

Carney, an Army Vietnam veteran, began writing as a response to the rude reception he and other Vietnam War vets received upon their return. He has since written many stories, some not involving his military experiences at all.

Other stories did address his time in uniform – but only to a point.

He could write about pre-combat experiences, such as events that occurred in basic training.

But he did not believe, as a writer, that he was ready to directly address the memories of the combat experiences he endured as a platoon leader in 1968 until he received assistance from a Veterans Affairs psychiatrist in 2016.

“He helped me find a way to get to describe those experiences objectively, as much as that was possible,” Carney said.

Not long after he published his book “Command at Dawn,” which directly references his personal recollections of combat.

Also last week, Katherine Iwatiw Menges of Kansas City, a 10-year Army veteran, read her account of when, upon reporting in 1984 to her first tour as a combat medic in Germany, a Nuremberg hotel employee refused to believe she really was a private first class, despite her green military identification card.

She spent a few hours on a lobby couch before the employee finally checked her in.

She wrote up the story recently, some 38 years after the incident occurred. It will appear in the Veterans’ Voices fall 2022 edition.

“I’m a feminist and in 1984 women weren’t considered equal in the military,” Menges said. “This was one of those moments that gave me hope that at some point I would be treated as an equal.

“I have many stories from my time in the military and this was one of the more humorous ones I have shared. Seeing it in print, and then hearing the reception to it from an audience, made me feel good about this particular life event I had experienced.”

Not the Humvees He Expected

Jason Kander knows the feeling.

Since earlier this year, when he published his memoir “Invisible Storm: A Soldier’s Memoir of Politics and PTSD,” Kander has appeared before audiences that included veterans and non-veterans alike.

“It’s really gratifying when you can see people seeing themselves in what you are saying,” Kander said recently.

“When you do a speaking event, you get to see that happen in real time.”

Following the 2001 terrorist attacks Kander, who grew up in the Kansas City area, enlisted in the Army National Guard. After graduating from law school in 2005, he served four months in Afghanistan as an Army intelligence officer, conducting corruption and anti-espionage investigations of individuals within the Afghan government.

That, Kander said, “required me to go outside the wire” – outside the military base or compound – “and deal with folks of questionable allegiances.”

Years later, he chose to write about it.

In 2018 Kander published “Outside the Wire: Ten Lessons I’ve Learned in Everyday Courage,” in which he discussed his two terms as a Missouri state representative and his time as Missouri Secretary of State in the context of the realities of his service in Afghanistan.

That included, he wrote, driving Afghanistan roads possibly studded with improvised explosive devices, not in the armored Humvees he had imagined before arrival but instead in unarmored civilian sports utility vehicles.

The bulk of his new book, Kander said, while detailing the basics of his Afghanistan service, concentrates far more on the time he spent, “dealing with the aftereffects of having deployed and dealing with untreated and undiagnosed PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder).”

“After having gone to treatment and gotten a lot better, it occurred to me that if a book like that had existed back when I first came home from Afghanistan, I think I might have gone to get help then,” he said.

“I felt I needed to write this book for those who were in the situation I had been in.”

The process of writing about his treatment benefited him, Kander added, as it “forced me to really come to a place where I had a clear personal understanding of my own journey.

“In therapy, I learned about my brain and about my experiences.”

And to accurately convey those lessons to others, he said, “I had to deepen my own understanding and really concentrate on these lessons in a way that would make it as clear as possible.

“If you are going to make this clear to other people, it first has to become very clear for you.”

One Too Many Trips

In the years since 1970, when Eisenbrandt returned from South Vietnam, began her civilian nursing career, married a Kansas City area lawyer and started a family, she had packed away the bulk of her war-time remembrances and keepsakes.

The spiral-bound journal, however, she kept close at hand, in a bedroom drawer.

“I always knew where that was,” she said.

In that way, for the next approximately 45 years, Eisenbrandt kept her war-time recollections at arm’s length.

Several things changed that.

One was the constant encouragement from Gary Swanson, the Kansas City area volunteer who spent years collecting and videotaping the oral histories of more than 1,000 area veterans.

She needed to write her book, Swanson insisted.

Another supporter: Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg, the former Kansas poet laureate and writing facilitator at Turning Point, the Leawood nonprofit that provides support services to adults and families living with serious or chronic physical illness.

Eisenbrandt is a former Turning Point board chair.

But it was one of her several return trips to what is now the Socialist Republic of Vietnam that Eisenbrandt believes finally pushed her to address her war-time experiences.

In 1994 President Bill Clinton lifted the U.S. trade embargo against Vietnam, some 19 years after the fall of Saigon to communist forces.

Suddenly Vietnamese officials were welcoming tourists.

At the time Eisenbrandt was working as an area travel agent, and with other agents she took the first of several trips in search of closure.

When she first returned from South Vietnam in 1970, she noticed how quickly she could tear up at comparatively trivial events. Even routine business calls that did not get a prompt response caused her eyes to grow misty.

She never had suffered the more debilitating symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

But her last visit in 2014, about 45 years after she first had deployed, triggered emotions that previous trips had not.

As on previous trips, she had chosen to visit the tunnels of Cu Chi, the subterranean network of passageways, near Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, used during the war by the communist guerrilla troops known as Viet Cong.

She also was aware of a nearby range, an attraction where tourists could fire automatic weapons at $1.50 a round.

Her 2014 visit to the tunnels coincided with the arrival of an especially motivated group of tourists to the firing range.

“At first I was fine with constant rat-a-tat-tat, but a second later I was not fine and started crying and couldn’t stop,” Eisenbrandt said.

“There had not been anything that triggered a bad response until then,” she added. “I guess what that told me was that you never really leave such an experience behind.”

She came back to Kansas City and retrieved the 1970 journal from her bedroom drawer.

Her book “Vietnam Nurse” appeared a year later.

This year Eisenbrandt published a second memoir, “Unsteady As She Goes: Battling Parkinson’s After Vietnam.”

In her first book she had only briefly detailed how, in 2003, doctors diagnosed her with Parkinson’s disease, which Eisenbrandt attributes to her exposure to the defoliant Agent Orange used by American forces during the war.

That’s now also part of her Vietnam legacy.

“It’s been gratifying because the entire goal with my books, as well as in my speaking engagements, is to not allow the world to forget about Vietnam,” she said.

“For so many years we couldn’t even talk about it.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author. He is serving as president of the Jackson County Historical Society.