Five Things We Learned About Thomas Hart Benton

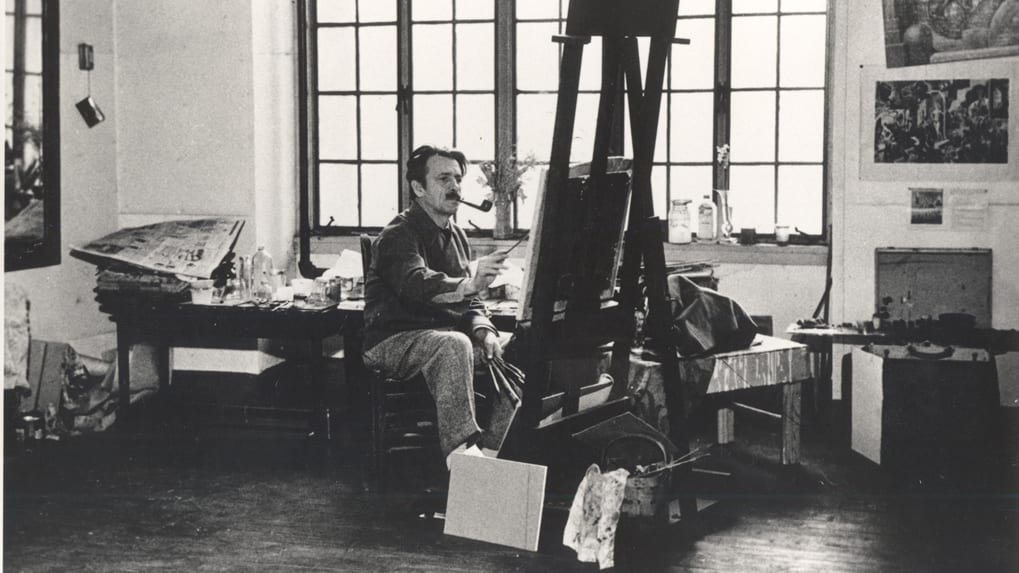

Thomas Hart Benton in his studio. (Credit: Thomas & Rita Benton Trust, UMB Bank, n.a., Trustee)

Thomas Hart Benton in his studio. (Credit: Thomas & Rita Benton Trust, UMB Bank, n.a., Trustee)

Published November 16th, 2015 at 7:55 AM

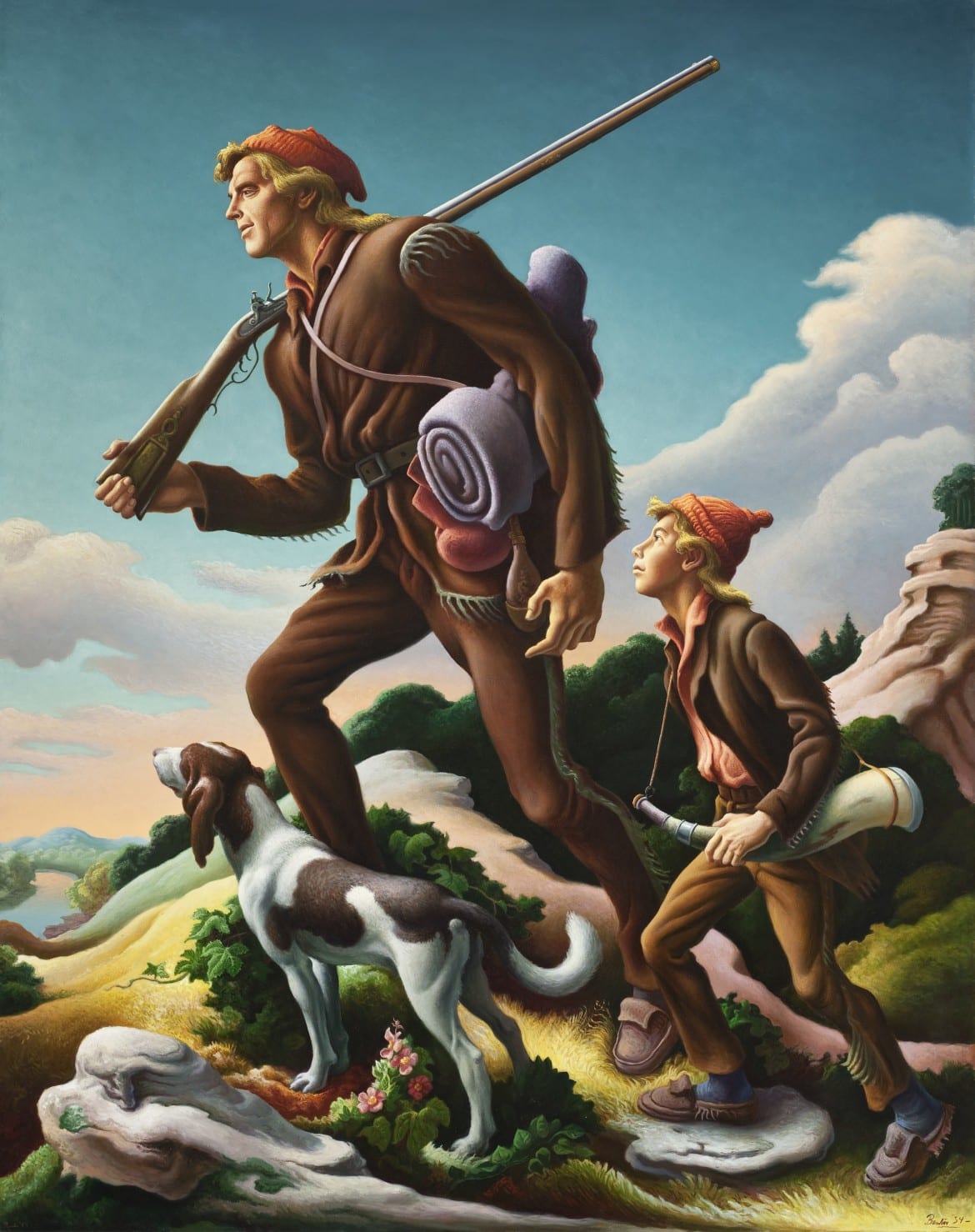

“American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood” is a landmark event. The show, which runs until January 3, 2016 at the Nelson-Atkins Museum, is the first major retrospective of Benton’s work in more than 25 years. It’s also the first exhibit ever to really put Benton’s work in proper context.

Featuring nearly 100 works, including more than 50 paintings, drawings and lithographs, as well as video clips, film memorabilia and personal effects, “Epics” explores the profound and intimate connections between Benton’s art and the film industry. Curator Stephanie Knappe gave Flatland a guided tour of the show this week, and these are the Five Things We Learned.

1. Benton was ridiculously famous.

Certainly the painter is one of KC’s favorite sons, but “Epics” shows just how hugely popular Benton was outside the Midwest. With the possible exception of Norman Rockwell, Benton was the preeminent face of American art in the first half of the 20th century, predating his student Jackson Pollack and, later, Andy Warhol.

Benton was, for instance, once interviewed by the legendary journalist Edward R. Murrow; a kind of coronation for anyone in the arts. (Visitors to the Nelson can watch that interview on a vintage TV set in a slightly kitschy section of the exhibit modeled after a mid-20th-century suburban living room.) He was also the first ever visual artist to grace the cover of Time Magazine. That level of national attention, Knappe told me, won a lot of new students for the Kansas City Art Institute, where Benton was an instructor.

2. His connection to the film industry, metonymically called “Hollywood” for this show, was deep and profound.

One of his earliest professional gigs was in Fort Lee, New Jersey — the first center of American film production. There, between 1913 and 1917, Benton painted backdrops for silent filmmakers, and he became fascinated by what would soon become the world’s preeminent form of storytelling. In fact, he became maybe the first, and certainly the best, America painter to fully integrate the grand, Jungian mythmaking aesthetic of cinema into his work.

Later, in 1937, Benton was able to unleash that understanding of film when Life Magazine sent him to Hollywood to create images of the film industry. Benton, always one to love shattering mythology, painted the sometimes glam, but also often unseemly behind-the-scenes worlds of Tinseltown. His editors at Life were, put mildly, not pleased. They refused to publish anything from the commission.

3. Benton even adapted cinematic techniques into his work.

For example, the artist would fashion three-dimensional clay models of paintings, then light them like tiny film sets before rendering the scene on canvas. The effect, which recalls Tintoretto, gives his work a depth, luminosity and vibrancy that few modern painters have ever matched.

4. Though now known mostly for scenes of daily life, particularly in pastoral America, Benton was ferociously political.

Critics, in fact, complained about it. Much of his work had a leftist, almost socialist bent. Like “American Historical Epic,” for instance, the work that gives this exhibit its name. The vast, sweeping series of 14 large canvases depicts the European conquest of North America with imagery that Noam Chomsky or Howard Zinn would embrace.

Benton also created some shockingly vivid anti-Axis war propaganda, maybe the most visceral and emotionally urgent work in his oeuvre. “Again” and “Exterminate” are particularly effective; gripping and graphic, with Dali-esque sense of the surreal. He created those works quickly too, completing his eight anti-fascist paintings in just under four months.

5. Benton, something of a polymath, turned himself into quite an important musicologist and folklorist.

When he wasn’t painting and drawing, Benton was traveling the country, documenting the wondrous variety of American musical expression. He also, not for nothing, played harmonica. Pretty well, too. Benton recorded an album with his musician friends, Saturday Night at Tom’s House, that came out on Decca. He even created a system of harmonica notation that’s still in use today. That alone would be a solid claim to fame even for someone who wasn’t one of the finest painters America has ever produced. But, as “American Epics” clearly shows, Benton was that as well.

“American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood” runs through January 3, 2016, at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. For more, watch KCPT’s Arts Upload as they walk the exhibit with its curator Stephanie Knappe and dig in to stories of local color from Benton’s time in Kansas City.