New Atlanta Ballpark Considered Model for Royals Coming Downtown

Published August 1st, 2022 at 11:30 AM

(Editor’s note: This article was originally published April 13)

By Kevin Collison

If you’re curious about the game plan for a potential Royals downtown ballpark, the new home of the Atlanta Braves may offer some inside baseball.

Truist Field and its adjoining “The Battery Atlanta” mixed-use development were cited several times by experts discussing the “Future of Sports Facilities” at an event last week sponsored by the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce and Urban Land Institute.

The Atlanta Braves built more than a 41,000-seat ballpark in a public-private deal with suburban Cobb County when it chose to leave downtown five years ago.

As part of their big move, the ownership acquired 90 acres adjoining the ballpark and partnered with developers to build a nine-story, regional Comcast headquarters, a 264-room Omni Hotel, 4,000-seat concert venue, restaurants, bars and residences.

“It’s the development and the revenue waterfall from the development that is really the justification for the investment in the stadium,” Irwin Raij, a national sports business consultant, said at the Chamber/ULI event.

“There’s definitely lessons to be learned.”

The Battery Atlanta, a mixed-use development with offices, residences, restaurants and bars, was built next door to the ballpark and attracts customers year round. (Photo courtesy Mortenson Construction)

John Shreve of Populous, the renowned Kansas City sports architecture firm assisting Royals owner John Sherman consider a downtown ballpark, agreed the Braves experience was a good example.

“It’s a pumping, vibrant urban public space which is what Kansas City could probably use in addition to some of the things you have at Power & Light,” Shreve said. “There’s a lot of lessons to be learned from there.”

According to sources, that’s the kind of plan Sherman is considering for a ballpark project that would likely be in the East Village. It would include what’s called ancillary development such as office, retail and residential to generate additional revenues.

Most of the 15-acre East Village redevelopment site, which runs from Eighth to 12th streets between Cherry and Charlotte, is controlled by VanTrust Real Estate. The area also borders several more blocks of underdeveloped property.

In Atlanta, Irwin said the ball club knew it wanted to generate additional revenues by leveraging the draw of its ballpark.

A street view of The Battery Atlanta. (Photo courtesy Mortenson Construction)

“It’s busy every week of the year whether there’s a game or not,” he said.

“The district is active all the time, restaurants are open 365 days a year and are full for lunch and dinner. You have a concert venue, these hotels and this stadium which is like the secret sauce.

“To me…having the mixture of corporate, entertainment activities and making a walking area, I think is really tremendous.”

Shreves said Truist Field, a Populous project, was designed to integrate with The Battery Atlanta development.

“In some ways its a very unconventional design of a ballpark because you don’t enter at home plate, you enter in the outfield,” he said.

“The thing that does as an opportunity is that outfield becomes this porous demarcation that’s a threshold that naturally leads into this amazing (Battery Atlanta) plaza that’s a concentration of all these restaurants.”

Fans enter Truist ballpark on the outfield side, creating a “porous” connection with the adjoining entertainment district. (Photo courtesy Mortenson Construction)

The Populous architect also observed the Atlanta ballpark complex emphasizes local cuisine and works with emerging chefs to provide its food service.

“You have this constantly rotating, changing idea of food and beverage which is a parallel to Kansas City and then likewise with our arts program, local artists and musicians,” he said.

Irwin said the Battery development has proven so successful, three additional hotels have gone up besides the Omni.

“If you ask the team, they’d put 100 more rooms on that (Omni) hotel tomorrow if they could,” he said.

The Braves ballpark cost $452 million to build. Another $672 million was invested in Battery Atlanta. The price tag for a Royals ballpark that wouldn’t start construction until later in the decade will be substantially higher.

Irwin said the ancillary development pursued in Atlanta to support the ballpark is key to making it work financially.

One concern about a downtown ballpark is parking. This image shows the Truman Sports Complex and its parking lots cover an area almost as large as downtown and all its garages within the Loop. (Image by Populous)

“If not, it’s really hard now because the building becomes so expensive to actually justify putting in real money for the stadium,” he said.

One thing that may be in the mix for a downtown Royals ballpark that’s currently not at the Atlanta complex is gambling.

Irwin said that with legalized sports betting, most new sports facilities are planning to add betting parlors. He added they don’t have to be large spaces, with some as small as 2,000 square feet.

“It’s an interesting driver and there’s real revenue opportunity,” he said. “It’s part of the entertainment factor of coming to an event.

“If it’s legal, I’m seeing it in almost every building I’m working on that there’s a space dedicated to sports betting.”

Both panelists also said regardless of whether a downtown ballpark comes to fruition, the community will need to make a major investment upgrading its professional sports facilities for the Royals and the Chiefs.

“To think there’ll be nothing, you’ll build a stadium or you won’t, either spend $10 or spend zero, that’s not the equation,” Irwin said.

“The debate is not a question of build new or nothing, it ends up being the debate being build new or renovate, and then what’s the pros and cons.

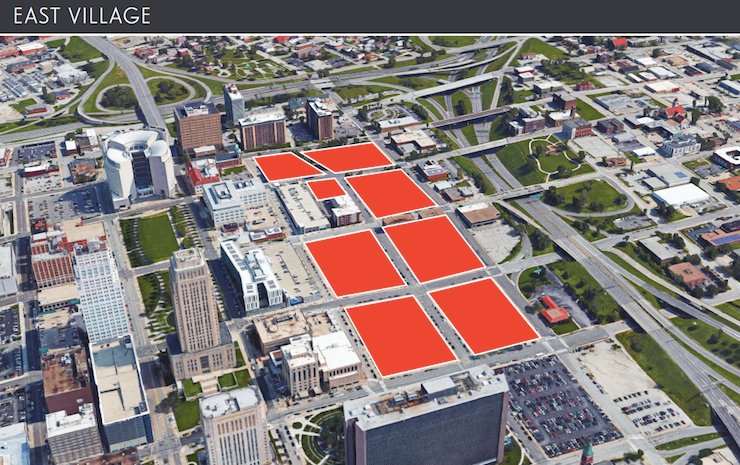

The East Village redevelopment area occupies eight blocks near City Hall.

“With renovation, you know exactly what you’re getting. You have the economic development that comes with the teams as they are today.

“In a new building, if they want to build one of the examples that John (Sherman) is referring to in the urban core, mixed use and entertainment district.

“That a different investment that comes with a different return.”

Shreves said the Truman Sports Complex was a state-of-the-art approach to providing great facilities for professional teams when it opened in the early 1970s.

“I’m not here to say whether both of those stadiums should remain intact as they are,” he said.

“That’s the great debate we as a community will have in terms of coming to grips with those as historic, great entertainment assets.”

“Also keeping in mind that like cities these kinds of community assets are always in evolving state with the needs and desires of the citizens of that particular time.”

The conversation about Kansas City and its professional sports facility future will continue April 22 when the Downtown Council holds its annual luncheon.

The event will include a panel discussion on “how sports and entertainment activate downtowns and connect communities.”

Among the panelists will be Mark Donovan, president of the Chiefs, who set off a border skirmish recently when he said the Chiefs had been approached by developers on the Kansas side of the metro about potentially building a home for the team there.