Black Appalachian Artists Showcased in Kansas City Kansas City Kansas Community College’s First Exhibit of 2023 Puts Black Artists from the Appalachian Region Front and Center

Published March 10th, 2023 at 9:00 AM

Above image credit: Shai Perry is gallery coordinator at the Kansas City Kansas Community College. She is also an artist and is from Tennessee. (Vicky Diaz-Camacho | Flatland)Shai Perry never imagined the exhibit she coordinated would connect with Kansas Citians.

The modest-sized gallery houses 10 artists’ works in an exhibit entitled, “Holler If You See Me: Black Appalachia” until March 31. Perry, the gallery coordinator at Kansas City Kansas Community College, organized it with her roots in mind.

“I just love to be able to share it,” she said. “And it’s been an awakening experience.”

Perry is from Tennessee and worked with two curators to bring works by 10 Black artists from the Appalachian Region to the Midwest. Karlota Contreras-Koterbay and Lyn Govette, the co-curators, sought to include artists in fine art and those who were self-taught. Contreras-Koterbay is the director of Slocumb Galleries at East Tennessee State University. Govette is a fiber artist and a curatorial fellow.

Both curators sought to elevate Black artists from the same region to tell their own stories.

“We wanted to really accentuate that element of empowered gaze, a gaze of resistance, gaze of descent. A gaze of the agency,” Contreras-Koterbay said.

Govette agrees. For years, she noticed how large galleries overlooked work by Black, Indigenous artists, and other people of color. So, she and her colleagues continue to organize exhibits that put BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) artists at the center.

“I feel that as a nation, we’re poor in ways of — we don’t understand the rich cultural heritage of everybody,” she explained. “I’m real happy to say: ‘Hey, look what we found. Come see this. Come enjoy it because it makes us richer.’”

The resulting exhibit displays each work on a level playing field, each identified by a label with the artist’s name and their medium.

Connection and Belonging

The curators and a few of the featured artists were happy to share their process and connection to Black Appalachia. Common themes emerged.

Artists explored motifs such as identity, displacement, loss and empowerment.

Some investigated the evolution of their childhood neighborhoods.

That was the case for Anissa Lewis, whose work manipulates buildings and signage.

Two mixed media works repurpose images of buildings that were once occupied by people in her community while growing up. The buildings had begun to crumble, as her neighborhood experienced disinvestment while other parts of the city were being gentrified.

She allowed the weathered building’s features to seep through superimposed black and white photos from her childhood. The intent, she said, was to highlight the humans who made the structures home and comprised her community.

Though she enjoyed her work as an engaged artist and educator in Philadelphia, Lewis felt the pull back home in Covington, Kentucky. She lived and worked in Philadelphia after graduate school, primarily in the Puerto Rican hub. Her newfound networks sparked a desire to reconnect with her roots.

But when she returned to Kentucky, the people she knew were long gone, homes were empty and Lewis felt disconnected — like an imposter.

“Long story short, I felt very much like a walking ghost,” she said. “The very people who were there to put into me and why I value community, why I valued collaboration, weren’t there.”

She added: “That work was about acknowledging that history, acknowledging what it afforded us by having that connection.”

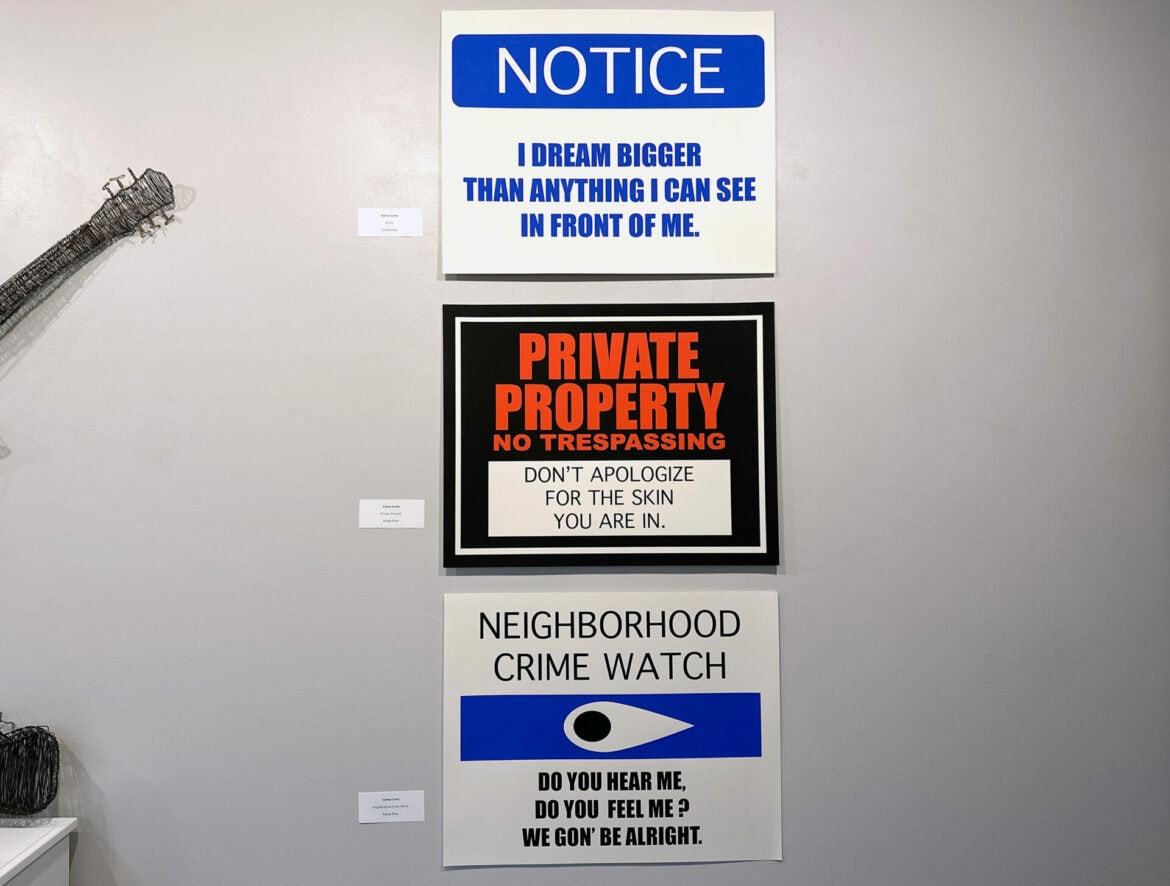

Through art, Lewis has connected the dots. Her work appears along another wall in the gallery, which displays three signs hung one on top of another.

Lewis added lyrics from neo-soul songs by artists such as Kendrick Lamar or PJ Morton to “No Trespassing” and “Neighborhood Crime Watch” signs. Her choice of lyrics and genre “heralds all things Black love,” she wrote on her website.

“I started taking the signage in our neighborhoods of how we govern ourselves,” she explained. “Who’s allowed to be here? Who’s not allowed to be here? What we can and can’t do with our spaces.”

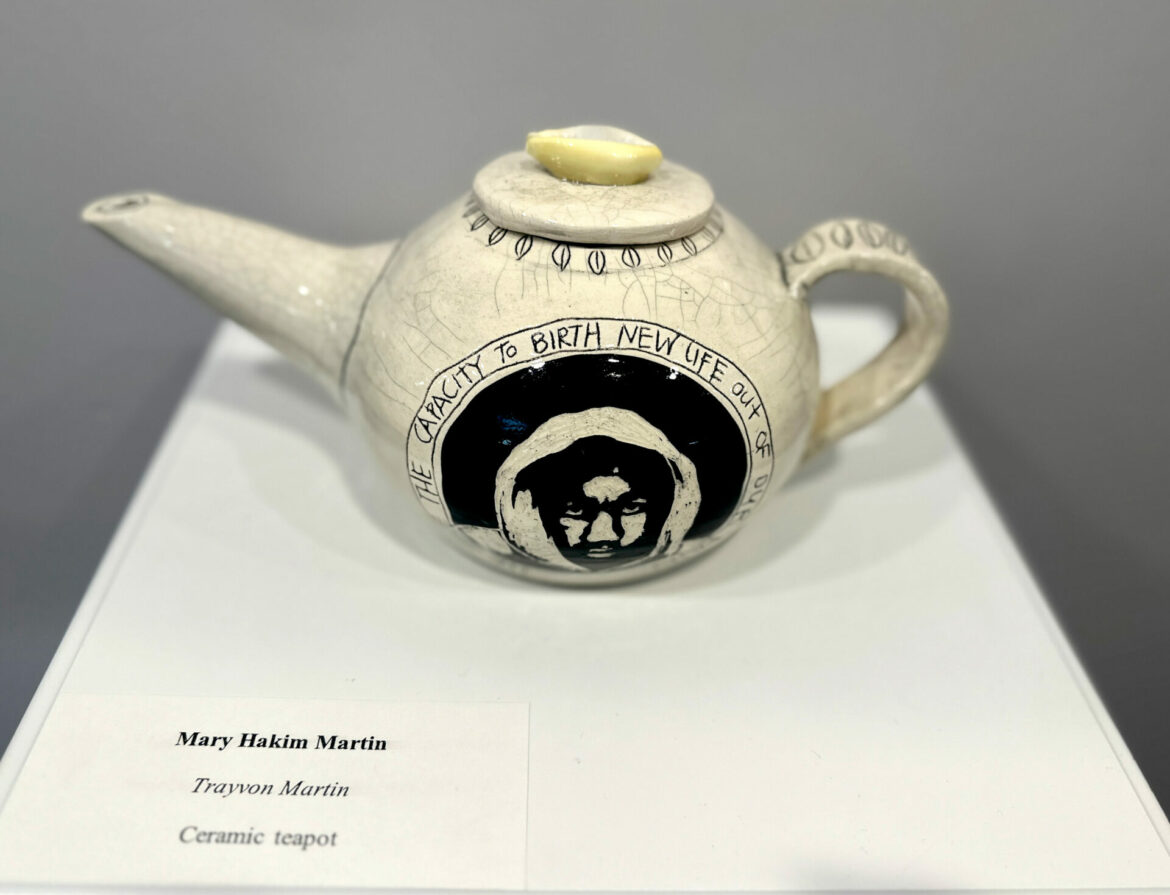

Another artist, Mary Martin of Pittsburg, took to ceramics — using West African symbols, coded language etched into the vessels and a collection of teapots with messages and imagery. Martin said she grew up in a time when gang violence was rampant, so her focus was on Black life despite tremendous loss.

She had lost most of the Black males in her life to violence. The artist recently put those stories in context with the violence seen across the country and thought of her son.

“It’s important for us to see patterns that exist and to make sure that the stories are heard,” she said. “In so many ways, the art becomes a way of even archiving and documenting our culture.”

The choice of the vessel hearkened back to her childhood kitchen table. Tea encouraged conversation, which provided her with a sense of comfort. Her use of a teapot represents a desire to resolve conflict through discussion.

“There’s so much negative that can consume us. But we need to be able to find a way to embrace hope,” Martin said.

Finding Self

Positive influences inspired another artist, Jonathan Adams. In this case, he drew on experiences being raised by his grandparents. Adams acknowledged the absence of his parents while elevating the importance of having figures like his grandmother to care for and empower him as an artist.

One of his works on display was informed by his grandmother, who was an artist as a young woman. Adams recounted that his family is full of artists, but their stories usually end with deserting that passion. After his grandfather died, he grew closer to his grandmother and learned more about her artistic leanings.

He asked her who she was and who she dreamt of being. The portrait shows a smiling woman, surrounded by red lightning bolts and foliage. It was Adams’ homage to the woman who raised him.

“(I told her), ’You may not be able to put yourself out there, but I’ll put you out there.’ I wanted to make her an icon,” he said. “I think about all the times that I could have been in a children’s home, or I could have been with somebody else living a totally different life.”

Lewis, Martin and Adams are several of the fine artists in this exhibition. However, the curators intentionally included artists whose foray into the art world was not via an art class or degree.

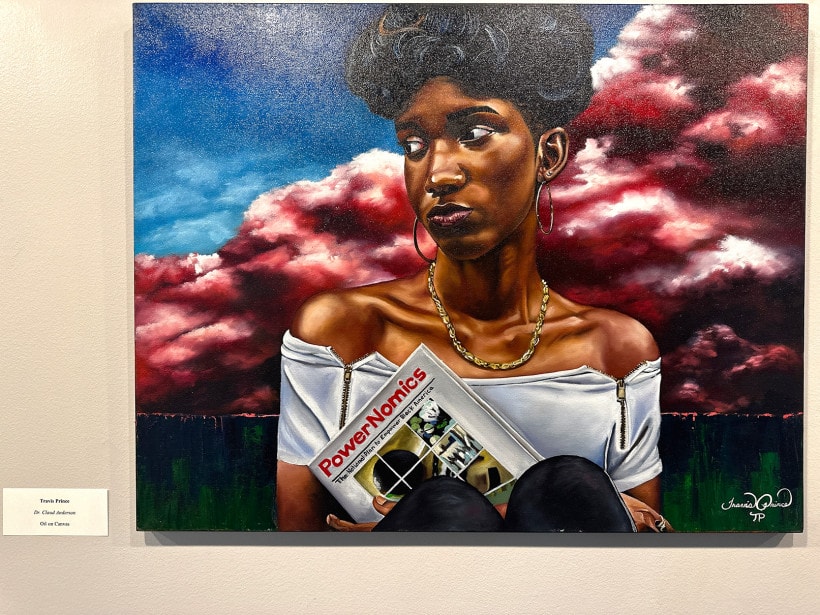

Self-taught artists include Travis Prince. His journey began with learning about Black intellectuals and little-known literature. Each book he read inspired him to expose others.

“We all play an important part in the human story.”

Travis prince, artist

He settled on what he called a simplistic, straightforward approach. A portrait artist by trade, he grips the viewer with an image of a Black woman, her face highlighted with strong shadows and deep contrasts with jewel tones. But the focal point is a white book by Dr. Claud Anderson, entitled “PowerNomics.” Anderson’s three-part text is known for analyzing and providing solutions to curb deeply entrenched racial disparities that affect Black folks’ wealth, businesses and class.

Prince painted the book in the foreground with the intent to stir curiosity.

“(I am) trying to bridge this gap in our understanding of American history, and the understanding that we all play an important part in the human story,” he said. “We are all valuable.”

Threaded through the exhibit are senses of place, identity and vulnerability. The artists are all from the same region as the gallery coordinator who now calls Kansas City home. And the two Appalachian transplants, the curators, who intentionally brought together various lived experiences, mediums and works.

The artists all shared gratitude to have the support of curators of color such as Contreras-Koterbay, LGBTQ allies such as Lyn Govette and young biracial gallery coordinators such as Shai Perry.

Their united goal is to educate.

“The best way to teach accessibility and (diversity, equity and inclusion) work is through art,” Perry said. “Because every single culture has an art form. … It is an unspoken language.”

“Holler If You See Me” features the following 10 artists: Jonathan Adams, Akintayo Akintobi, Lynn Bachman, Tramel Fain, Pam Faw, Jason Flack, Dexter Greenlee, Anissa Lewis, Mary Martin and Travis Prince. Their work will be on display at Kansas City Community College on 7250 State Ave. until March 31. The art gallery is on the lower level of the Admissions Building, room 2346. A closing reception will be held on March 31 between 4:30 p.m. and 6:30 p.m.

Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs for Kansas City PBS.