New Exhibition Asks Crucial Question: Where Are the Birds? Linda Hall Library Examines Climate Change Quandary

Published November 22nd, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Eric Ward, vice president for public programming for Linda Hall Library, standing between two of his three photographs shown at the ornithology exhibition. Ward is particularly fond of the Brown-headed Nuthatch reintroduction display next to his pictures. He describes their distinct call as “sounding just like a rubber ducky.” (Chihiro Kai | Flatland)The birds of North America are dying. Their fading songs are a disquieting alarm for the health of the environment.

“We are in an absolute global crisis of biodiversity, and we haven’t quite realized it yet,” said Dr. Eric Dorfman, president of Linda Hall Library and director of the exhibition, Chained to the Sky: the Science of Birds, Past & Future.

“Birds are just one of the casualties. But just like the fabled canary in a coal mine, if the birds are falling over pretty much everything else is too.”

A wildlife ecologist and former director of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Dorfman dedicated his inaugural Linda Hall Library exhibit to humanity’s 17,000-year history with birds. The exhibit opened Nov. 10 and runs through April 26, 2024.

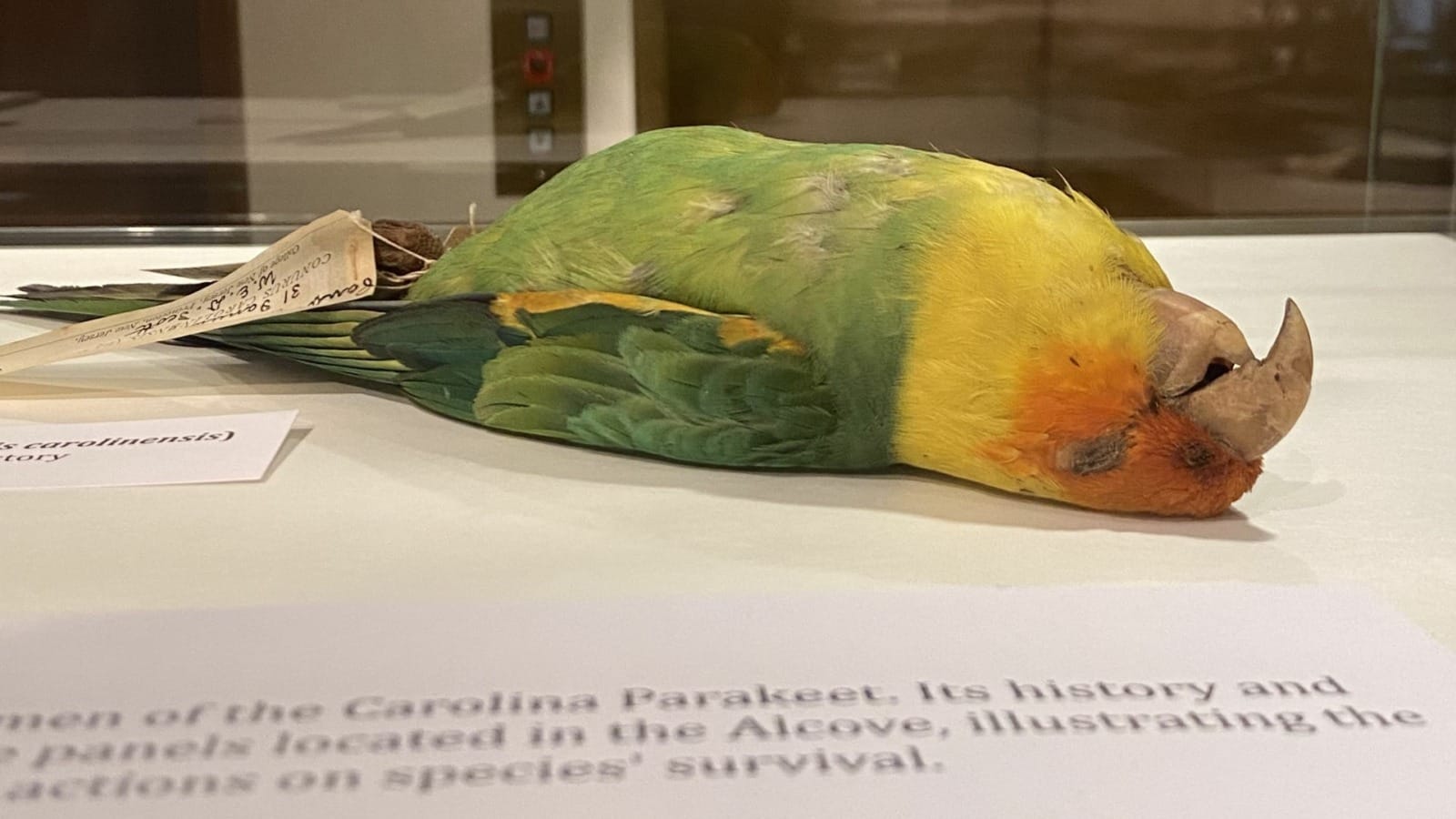

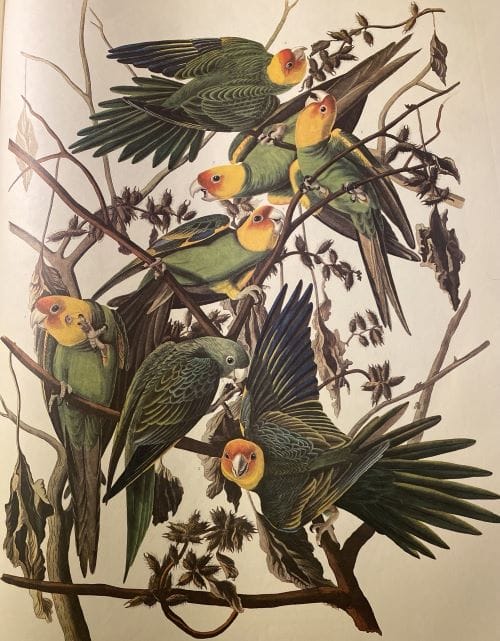

Taxidermied specimens, on loan from the Field Museum of Chicago, are arranged within the context of Western anthropology. Beginning with the Lascaux cave painting “Bird Man” found in France and ending with the illustration-rich first edition of “The Sibley Guide to Birds” from the year 2000, the exhibit is his tribute to the birds man has loved and lost.

According to Dorfman, the exhibition was inspired by the 2019 Science research article “Decline of the North American Avifauna,” one of the most comprehensive assessments of North America’s birds in 50 years.

The data was devastating. The article reported a population loss of nearly 3 billion birds since 1970. From urban landscapes to coastal forests, the continental United States and Canada had lost an estimated 29% of its feathered residents. The authors of the report noted this was a conservative estimate, and the actual figure could be much higher.

Out of all North American biomes, Dorfman said the grasslands, which cover 95% of Kansas, recorded the heaviest casualties — about 720 million fewer birds, less than half of the 1970 population.

Although extinction is a natural process of life on earth, the Science article noted that human activity has accelerated the phenomenon by “a thousandfold” compared to estimated pre-human rates.

Dorfman said the devastating decrease in bird populations is symbolic of a much larger problem.

“There’s a famous analogy of rivets on a plane, right? So, you’ve got a plane that’s flying in midair, and you pull out one rivet, and every rivet is a species,” he said. “You pull out one rivet, the plane will be fine. It will keep flying. You pull out 10 more rivets, the plane keeps flying. It’s no problem.

“But then you pull out the one rivet that’s the straw that broke the camel’s back. There is one rivet that you will pull out that will make the entire plane crash.”

According to Dorfman, there are currently no methods for predicting what species serves as the fatal rivet in any given ecosystem.

This is why birds, which people have studied for millennia in their abundance and wide range of habitats, are outstanding indicators of environmental and climate conditions. Their unparalleled mobility and adaptability, most readily recognized in migratory species, allow birds to move with the shifting biome and temperature domains.

Flocks can serve as mirrors of invisible atmospheric and biological phenomena that scientists would otherwise track with equipment and computers. Their absence or sudden emergence prompts questions about their food chain, such as, “What’s happening to the pollinators that feed the birds?” Dorfman said.

Bird’s-Eye View

Flatland has summarized national data on avian loss from the Science article, the 2019 National Audubon Society climate report, and other ornithology publications focusing on threats to Kansas and Missouri birds.

The Audubon report assessed the vulnerability of North America’s birds under the assumption that global temperatures will increase between 2.7 degrees and 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit above pre-industrial levels by 2100. (Even if every participating nation in the Paris Climate Accords, a legally binding United Nations treaty to fight climate change, met their greenhouse gas reduction goals, the global temperature is expected to rise by at least 5.76 degrees Fahrenheit.)

According to Audobon’s state-specific climate briefs, both Kansas and Missouri can expect a 12-degree Fahrenheit spike in the average summer temperatures, and up to 110% reduction in available moisture by 2100. In addition to suffering both immediate and long-term effects of climate change, such as extreme weather and drought, the fate of local birds are intrinsically tied to the states’ agricultural industries.

The continued conversion of native habitats into croplands has devastated Kansas and Missouri birds, particularly in the grasslands.

The Audobon report expects climate change to exacerbate agricultural expansion and land abandonment rates at least until the global thermometer change reaches 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit and above. Past this point, the climate conditions will prove too severe for agricultural practices.

If there is to be any future for native birds, the two states must address their land-use policies before the planet confiscates their options, and their food.

Like bees and other insects, birds are invaluable pollinators and seed dispersers, without which the agricultural industry would not exist. Their predation of parasites and other bugs helps control pests, and their meals fertilize our soil.

Despite these contributions, birds consistently fall victim to unsustainable farming practices, like monoculture farming, over-irrigation and rampant use of pesticides, Dr. Dorfman said.

In terms of recreation, bird watching and related activities are a multi-billion-dollar industry in the United States, and one of the few that grew during the global pandemic.

A 2016 U.S. Fishing and Wildlife Services study estimated that 45 million birdwatchers generated nearly $96 billion in output, supported 782,000 jobs and contributed $16 billion in local, state and federal tax revenue. Nature reserves like the Cheyenne Bottoms Preserve don’t simply protect birds, like the critically endangered Whooping Crane with less than 700 remaining in the wild. Kansas and Missouri bird refuges attract revenue through ecotourism and related purchases.

Eric Ward, vice president for public programs at Linda Hall Library, is a bird enthusiast and took three of the photographs displayed in the exhibition.

“It’s not professional grade or anything. I just notice birds and take pictures when I can,” Ward said. “They’re really captivating to look at.”

How Can We Help Birds?

The good news is that both Missouri and Kansas have track records for successful bird conservation and rehabilitation.

Fittingly for the Thanksgiving holiday, the Linda Hall Library exhibition applauds the Missouri Department of Conservation for resurrecting the state’s turkey population. Through habitat preservation and regulations that promoted sustainable hunting practices, the state’s wild turkey population recovered from an estimated 2,500 individuals in the wild in 1950 to 300,000 today.

With the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1977, the United States government invested immense energy and resources into wetland conservation with a vigor not seen since President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act at the dawn of the 20th century.

As a result, the wetland habitat is the only biome in North America that has documented a growth in bird populations, including in Kansas and Missouri. Community scientists and bird enthusiasts can volunteer for conservation efforts at their local wetland refuges, and other sanctuaries critical to birds.

The final segment of the Linda Hall Library exhibit is devoted to providing information on how individuals can make a positive impact on their local bird populations. Dorfman said simple things, such as putting up stickers on windows and keeping bird feeders away from glass can significantly reduce bird strikes in urban and residential areas.

“If you have a garden space, plant native grass and flowers that will attract insects and the birds that eat them,” Dorfman said. “If you notice more birds in your backyard, you can expect a positive ripple effect across the food chain that is not as visible.”

Chihiro Kai is a science reporting intern at Kansas City PBS/Flatland. She is a student at the University of Kansas studying journalism and biology.