National Rural Health Day Highlights Growing Needs in Kansas Kansas Rural Health Association Hosts Conference Each Year On To Discuss the State of Rural Health Care

Published November 16th, 2022 at 9:00 AM

Above image credit: Members of Kansas Rural Health Association, Kansas Hospital Association and the Kansas Department of Health and the Environment join Governor Laura Kelly at the proclamation of National Rural Health Day at the Kansas State Capitol on Oct. 28, 2022. (Contributed)Taylor Zabel is the president of the Kansas Rural Health Association and a third year medical student at Harvard.

He’s also a fifth generation Kansan, raised on his family’s farm near Smith Center, Kansas.

“I have pretty deep Kansas roots,” Zabel said.

Once he’s finished with schooling and residency, Zabel plans on coming home to rural Kansas to practice.

“This work with the Kansas Rural Health Association, it’s been my labor of love,” he said.

The association is a volunteer organization working to unite rural care providers across the state and amplify their voices.

Zabel said Kansas has a lot of organizations with a vested interest in rural issues. His organization’s goal is to bring everyone together to identify the most important issues, and make sure they get in front of lawmakers.

Each year the organization hosts a conference in Salina, Kansas, to celebrate National Rural Health Day on the third Thursday of November.

During the conference, health care professionals gather to identify and unite around community needs. Several have been top of mind, not just during the pandemic but for the past several years.

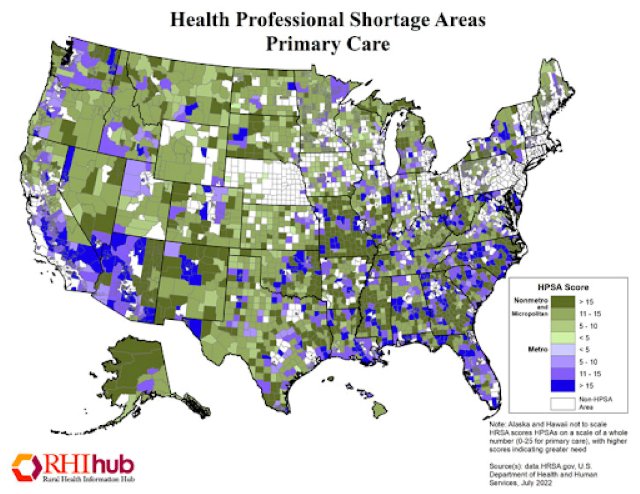

Kansas and Missouri rank 7th and 8th, respectively, for most rural hospital closures, according to Sidecar Health, a health care insurance company.

Citing the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s “Rural Hospital Closures,” the ranking shows how many rural hospitals have closed since 2005, how many beds were lost and the implications.

Since 2005, nine hospitals have closed in rural Kansas, including four in smaller or more isolated communities. In Missouri, eight have closed, including three that served small or isolated communities.

The ranking, which also cited Flatland’s report from 2021, shows that more than half of Kansas hospitals have been operating at a financial loss.

The closures — most of which recently happened in 2019 and 2020 — are revealing the stress points in what was already a fragile system. For instance, funding has long been an issue.

In 2014, the Kansas Hospital Association (KHA) wrote a memo detailing just that.

“A large portion of the public health and education responsibility has been shifted to the local level, making tax subsidy for hospital services impossible,” read the KHA memo. “Most communities have reduced or eliminated subsidies for hospitals and emergency medical services, leaving the health system to rely on its own resources.”

In October, the association presented a dire update. The key takeaways:

- Transportation resources are needed, with hospitals spread far and few between.

- Reimbursements from third-party insurance and/or Medicare are inadequate.

- Rural populations are aging, and may require more chronic disease management.

- Staff shortages caused by burnout, transition to higher-paying jobs such as travel nursing, or retirements are resulting in an over-reliance on mid-level practitioners.

- The majority of small hospitals are 35 miles away from one another, with limited emergency care facilities.

Zabel noted similar pain points from providers across the state and from his own experience. Workforce shortages and funding issues topped his list.

Michael Kennedy, a board member and founder of the Kansas Rural Health Association, said these issues have long plagued rural health care.

Kennedy recalled from his practice in Burlington, Kansas, and the first Rural Health Association meeting 11 years ago in Salina, that there was a big issue of uninsured populations in town.

Other key topics from that first meeting were issues of access to specialty care, a lack of community education around prevention and wellness and an aging population.

“A lot of the issues remain the same,” Kennedy said. “Payment systems are still broken. It’s unfairly stacked against small volume hospitals, like rural hospitals, and they’re feverishly looking at new payment systems and systems of practice of health care delivery, that the small rural hospitals can survive in.”

‘Still Fighting’

Primary care physician and emergency room doctor James Longabaugh has dedicated the past 25 years to being a rural doctor.

Then, 10 months ago, he became the chief executive officer of Sabetha Community Hospital (SCH).

SCH is a 17-bed hospital that serves a population of about 2,500 people, a rural community 60 miles north of Topeka. Although Sabetha isn’t as small as other surrounding rural towns, Longabaugh has witnessed an increase in expectations and needs.

These past couple of years have been difficult.

At the peak of the COVID-19 crisis, Longabaugh and his colleagues were forced to take in sicker patients, and were unable to transfer them to neighboring hospitals. At first hospitals like Sabetha lacked the equipment necessary to treat respiratory illness, such as the complications brought on by SARS-CoV-2.

The residual effects the COVID-19 crisis had are still felt today, save for a few lessons and “silver linings,” he said.

Longabaugh and Sabetha’s staff leaned on one another to do what he described as “out of their wheelhouse.”

“We learned what we can do,” Longabaugh said. “We really expanded our capabilities.”

Adaptability is a key element to rural health care.

Kennedy helped spearhead the Rural Health Education program at the University of Kansas School of Medicine and was the assistant dean of the program for many years.

Kennedy said he always reminded students that at a rural practice, the physician has to be able to do a little bit of everything.

While other professors would encourage the brightest students to specialize and go to urban hospitals, Kennedy would empower them to fulfill their dreams of being in rural medicine.

“You’re smart, and we need smart people to practice rural medicine because it’s challenging,” Kennedy said. “You have to be able to do everything.”

With one hospital in town, it also means there’s only one place to turn.

According to the American Hospital Association’s 2019 Rural Report, rural hospitals are more likely to serve higher percentages of Medicaid and Medicare recipients. U.S. Census data from 2017 reported over 10% of Kansans were uninsured, and rural counties reported almost 20% of their population was without insurance.

“There aren’t safety net clinics, so you’re it,” Kennedy said. “So you either take the patient or you don’t.”

In a small town, Kennedy said most folks knew if someone got turned away.

“So there was strong pressure to just take care of folks and then just write it off if they couldn’t pay,” Kennedy said.

This feeling resonates throughout the rural health care community. Simply put, there’s a lack of a robust health care network in addition to slim staff. They need solutions, and fast.

Like urban hospitals, rural hospitals hemorrhaged nursing staff because of burnout and anxiety. Still, the patients kept rolling in.

Expenses and needs mounted. People expected their community hospital to help them.

Longabaugh said the pandemic has had compounding effects on health care bandwidth. Not just that, as the crisis evolves, priorities have shifted to what’s most needed.

His top three needs are insurance reimbursement, mental health support and funding to attract future health care professionals. He’s also concerned about the population who needs the most support — those 65 years old and up.

The first issue has to do with the way rural hospitals get their money. Community hospitals are critical access hospitals that are paid based on their costs of taking care of patients.

After a slew of rural hospital closures in the 1980s, Congress established the Critical Access Hospital (CAH) designation. Critical access hospitals are designated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and are allowed to receive certain reimbursements for Medicare services.

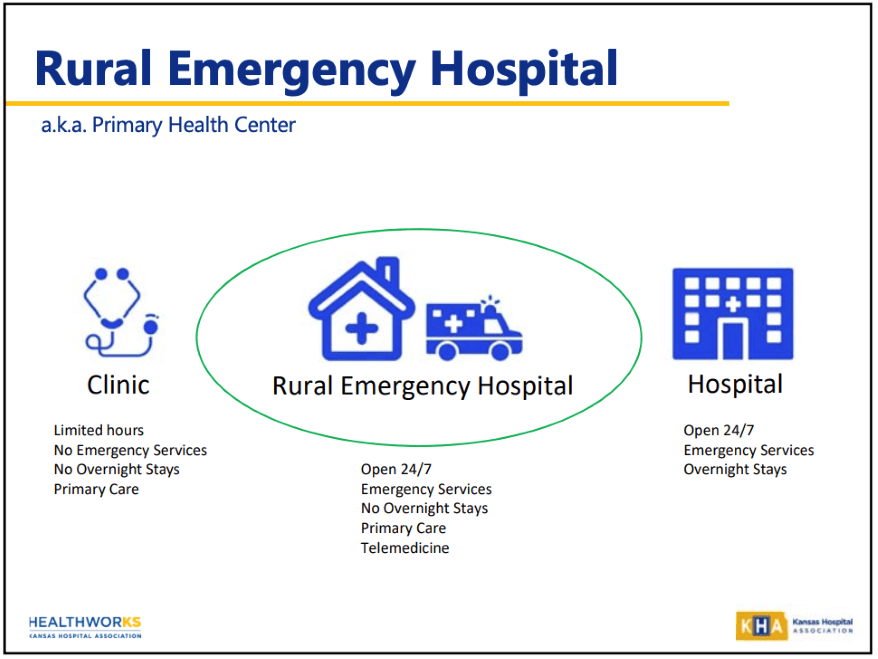

Then in April of 2020, to address concerns of more possible closures, a new federal policy established Rural Emergency Hospitals (REH).

“Conversion to an REH allows for the provision of emergency services, observation care, and additional medical and health outpatient services, if elected by the REH, that do not exceed an annual per patient average of 24 hours,” according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

There are 82 critical access hospitals in Kansas, according to Kansas Rural Hospitals Optimizing Performance (KRHOP).

Although the REH designation can help reduce the number of closures, Longabaugh said the requirements are too restrictive for some critical access hospitals.

“There are many CAHs in Kansas that would be eligible for REH status, but only a few will utilize that status,” he explained.

It mostly helps hospitals with a low volume of patients.

Once a local community’s critical access hospital converts to a rural emergency hospital, the care they provide changes.

“No inpatients, no (obstetrician) B. (Communities must) have very reliable EMS due to the frequency of potential transfers to higher level of care,” Longabaugh added.

Zabel’s hometown of Smith Center currently has a critical access hospital.

It offers a lot of services. It has an inpatient facility, does labor and deliveries and runs an emergency room and an outpatient facility, but the beds aren’t always full.

Zabel said this means providers make rounds between all of these departments.

“Providers are having to navigate between rounds both with their outpatient clinic, going to see patients who are admitted inpatient, helping with any emergencies that happen,” Zabel said. “It’s a lot to juggle as a rural provider.”

Plus, there’s a feeling that the whole facility could close its doors because it can’t support it all.

Rural communities might have a 15-20 minute drive already to their hospitals. A closure could increase those drive times to 45 minutes or an hour in some cases.

“If a person requires services that even the rural hospital can’t provide, that provides another (issue) that now you have no means of transporting or stabilizing a patient before they can be sent to a more tertiary care center, like KU Med or Wesley,” Zabel said.

Zabel said rural emergency hospitals will operate at lower costs by closing down some inpatient care, but keeping emergency departments and outpatient clinics running.

“It’s another way to restructure how hospitals are reimbursed… So they get a reimbursement for the services that they provide, in addition to facility payment that helps to keep the doors open,” Zabel said.

Rural emergency hospitals may begin operations in January 2023, but it’s unclear how many communities will embrace this structure.

According to a report by the NC Rural Health Research Program, Kansas has 16 potential community access hospitals that might convert to rural emergency hospitals, the most of any state.

There is also a dire need for mental health personnel. Longabaugh said the pandemic eroded confidence in the health care system, which hurt less-funded areas such as mental health clinics and staff.

“We still are fighting back from that,” Longabaugh said.

Today, places like Sabetha Community Hospital are trying to tie up a system bursting at its seams.

Mental health crises are among the top concerns of health care providers and patients in rural areas. More concerning, Kansas ranked last in the nation in Mental Health America’s recent report. It landed last for the high rate of mental illness and poor access to care.

In 2021, Bradley Dirks, a behavioral health specialist at Kansas State University called Kansas a “mental health desert.”

Dirks’ focus was on rural farmers, who may not find others who can relate to their specific stressors. However, his concern echoes that of other mental health experts who have sounded the alarm.

In an email to Flatland, he wrote: “It is of note that Kansas scores well below the national average and ranks 41st in the prevalence of mental illness and access to care.”

As stress points turn into pain points, there’s one lingering issue that has only gotten worse. The aging population is being left by the wayside.

There’s a lack of home health nurses, high turnover in long-term care facilities and nursing facilities are at capacity. Beds and rooms are available but there isn’t enough staff to care for residents.

This is a major concern for doctors like Longabaugh. Nearly 75% of his patients are on Medicare. Without access to the care they need, he said, the aging population risks more health complications.

He’s hopeful but cognizant of how vulnerable certain pockets of his community are right now.

Longabaugh put it like this: “If I could wave my magic wand, I would love to see more funding support for those areas, whether it be health staffing or mental health, staffing or reimbursement that allows more people to go into that as a career.”

Coming Home

It’s not all bleak.

In the almost 20 years he’s spent at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kennedy has seen an increase in young providers who are passionate about rural care.

“What we’ve found is that, yes, the numbers of students from rural settings that have come to KU with the idea that they want to practice rural medicine has grown,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy pushed to have the medical school list the education of students bound for rural practice as a priority of the school. To him, it’s vital to support students who want to go into rural practice, especially since most education facilities sit in urban areas.

That’s what worked for Zabel too.

Following his undergraduate degree at the University of Kansas, Zabel went to Washington, D.C., and worked at the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy.

“It helped to show that this isn’t something that I’m just interested in,” Zabel said. “There’s a network of people nationally who are vested in rural issues, and want to see me go into this field, and help support me in that respect.”

Zabel said it begins with support. Starting at the high school level, he wants students to know that a career in rural medicine can be fulfilling and rewarding.

Rural hospital administrators are also doing what they can to entice young physicians to work at their hospitals.

For example, Zabel noted that the hospital in Smith Center created a network of nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other family medicine providers to share the burden of being on call 24/7.

Some hospitals lean heavily into the service aspect of health care and will contract a physician for several months out of the year to allow the hired doctor to do global medical work.

“It’s just really tapping into what makes your community unique and how can you work with what you have to entice providers to your community, even if the salary may not be equivalent to what you can make in an urban area,” he said.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.