Missouri Farmers Add Carbon to Their List of Crops Farmers Are Getting Paid for Sequestering Carbon to Even Out Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Ecosystem Services Market Consortium (ESMC) collected soil samples from participating Missouri farmers. (Contributed)

Ecosystem Services Market Consortium (ESMC) collected soil samples from participating Missouri farmers. (Contributed)

Published February 22nd, 2023 at 12:00 PM

Jon Hemme farms about 1,000 acres of row crops in addition to his family’s dairy and cheese operation, Hemme Brothers Creamery in Sweet Springs, Missouri.

In 2018, Hemme started to implement cover crops and no-till practices into his soybean and corn crops to make the soil more resilient. In 2020 he joined a program to sell the carbon sequestered on his crop land.

“There was a small change that I could make on about 300 acres that would qualify me and I thought if I was doing the work anyways, it’d be kind of nice to be able to sell some carbon credits,” Hemme said.

Agricultural carbon credits are generated on farmland and sold to companies that want to offset their carbon emissions.

According to World Data Lab, global emissions have already reached more than 8.5 billion tons of C02 in 2023. The same data predicts more than 58 gigatons of greenhouse gas emissions this year.

A report from the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets estimated that a 15x scale of the carbon market by 2030 could have “meaningful support” to climate goals set by the Paris Agreement.

Missouri and Kansas have the potential to contribute greatly to this market thanks to their millions of acres of farmland.

Carbon farming seems like a win-win solution. But in the market’s preliminary stages, carbon credit payments are hardly large enough to incentivize (a practice) change among farmers.

What is Carbon Farming

Think back to middle school science class when you probably had to memorize the equation for photosynthesis.

Water and carbon dioxide are converted into glucose and oxygen, through photosynthesis, as a plant grows.

As a row crop (like corn or soybeans) grows, it takes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and fixes it into its plant material.

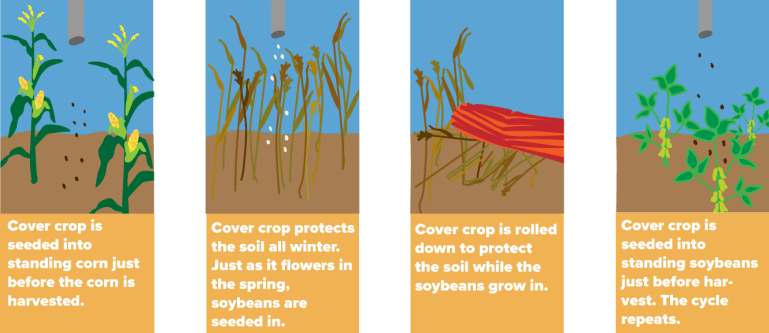

Read: Cover crops and no-till practices can benefit a farmer.

Some of this plant material is left behind after harvest, and if the farmer implements a no-till or reduced tillage practice, the carbon will (mostly) stay in the soil rather than being released back into the atmosphere as the plant decomposes.

A cover crop takes this a step further, ensuring row-crop acreage has carbon-consuming plants on it year-round.

To sell carbon credits, companies encourage farmers to adopt these practices into their operations and then calculate the amount of carbon sequestered to generate a carbon unit, or one metric ton of CO2.

Carbon sequestering practices are not new, and some farmers have been using them for decades.

Micah Cameron-Harp, a postdoctoral fellow at Kansas State University researching the social and economic effects of the agricultural carbon market, explained that carbon credits are far more valuable when they are generated on land that otherwise would not have sequestered that carbon.

“That carbon credit really doesn’t have the same quality as one that we can be assured (that) without an incentive, this producer was never going to do something like cover crop,” Cameron-Harp said.

Companies who contract with producers will typically only do so around a practice change. It also makes it easier to measure and predict the carbon sequestration rates.

That’s how Hemme got into the market.

He had been using a cover crop for his soybeans. To qualify for the carbon credit program, he added a cover crop to his corn rotation.

How does a cover crop work?

From there, it’s business as usual for the farmer, aside from some necessary data entry and soil collections.

Hemme participated in a carbon pilot program between Missouri Soybeans and Ecosystem Services Market Consortium (ESMC).

ESMC is a nonprofit aimed at assisting companies who want to reach net zero emissions. In line with that mission, ESMC sells carbon credits as inset credits rather than offset credits.

This means carbon sequestered on a soy/corn operation like Hemme’s would be sold within the soy or corn supply chain.

Jake Deutmeyer, a project manager at ESMC, said under this model, the companies buying the credits are helping to reduce their overall emissions, rather than just compensate for them.

“The company buying this credit is buying credit, but they’re also helping make their own supply chain more sustainable,” Deutmeyer said.

So why don’t companies just emit less?

It’s very costly to change a supply or power source for a big manufacturer who wants to be environmentally conscious. Instead of making a substantial change like that, a company will pay someone, elsewhere, to sequester some of the carbon it has emitted and balance out the equation.

“It may be very costly for (companies) to reduce emissions, and slightly less costly for somebody else to increase sequestration,” Cameron-Harp explained.

Usually, Cameron-Harp said companies will purchase more carbon credits than what their actual emissions were to account for any inconsistencies between the trade, but this can also depend on the entity contracting the carbon credits.

Fledgling Industry

The two-year pilot program between ESMC and Missouri Soybeans garnered a lot of interest from Missouri farmers. In total, it enrolled 15 producers and just under 5,000 total acres, according to Clayton Light with Missouri Soybeans.

Due to delays in the data collection and verification process, ESMC was unable to sell the credits from the first year (2021) of the pilot program, though it did send producers a partial payment for participation. Deutmeyer said the 2022 credits are being verified and ESMC is identifying a buyer.

Bayer, another company in the carbon credit market, sells offset credits, as opposed to the inset credits sold by ESMC.

Alyssa Cho, a sustainable agricultural field manager at Bayer said it has yet to sell any of the offset credits.

“That’s partially because carbon doesn’t just get sequestered overnight, it takes time,” Cho said, noting that Bayer’s program started in 2021. “So we won’t really know until we’re a little bit further into this process to understand what it all looks like.”

The demand for carbon credits is there, but the supply is not yet to speed.

“We would definitely need to get more growers into the program to meet the demand that’s there for these offset credits,” Cho said.

Most companies will contract a certain number of acres to generate carbon credits, but one carbon credit is not equivalent to one acre.

A carbon credit, one ton of sequestered carbon, can take more, or less land depending on the climate, crops and practices on the land.

Bayer uses a pay-by-practice method to give producers a better idea of the payment they would receive. As long as a grower commits to the practice change in their contract with Bayer, they will receive a set price per acre.

“What happens then is Bayer is absorbing that risk of how much carbon is actually being sequestered on that acre,” Cho said. “So we’re looking at it more holistically, trying to reduce the risk for the grower, but also ensure that they’re receiving incentives and payments.”

Missouri producers who switch to a no-till practice can expect $6 per acre, and an additional $6 per acre if they add a cover crop, according to Bayer’s website.

Other companies pay between $10-$20 per carbon credit. For many producers, the price point is too low to be an incentive.

Six dollars ($6) an acre is not much. That doesn’t even foot the cost of seeding a cover crop.

Currently, the United States are in a voluntary carbon market. In many other countries, carbon credits are sold under a cap-and-trade market or emissions trade system which issues pollution permits to a company. If a company pollutes more than its permit allowance, it has to offset it by purchasing more credits.

“So, that source of demand, then impacts the price,” Cameron-Harp said.

Prices for carbon units in the U.S. are lower because there is less of a demand. Companies buy carbon credits to please shareholders or consumers, but not because they must.

The industry is almost sure to boom in the coming years, as countries and large companies strive to meet net-zero benchmarks in 2030 and 2050. Some believe that a voluntary market, like the U.S. will be more effective in reaching climate goals by allowing producers to benefit nicely from wealthy corporations purchasing the credits.

To reach that scale it will take more than just row crop farmers adopting these practices. ESMC is working on projects in less-familiar territories, like almond orchards in California, or cotton farms in the south.

“I think this space is only going to continue to grow and we’re hoping that that translates into higher carbon prices,” Deutmeyer said.

Lasting Benefits

Cameron-Harp said the research team at K-State is investigating how much incentive someone needs to implement these changes and how it changes across regions.

In eastern Kansas and Missouri, it’s easier to grow a cover crop because of the wetter climate. Producers can reap additional benefits like improved soil health or an extra grazing pasture for cattle.

There are many reasons to implement these practices in these regions, so the low payment is seen as a cherry on top rather than the whole sundae.

But a producer in western Kansas might have a completely different outlook. In the drier climate, it’s hard enough to grow the cash crop, let alone allocate extra resources for a cover crop, so folks might need more of an incentive to implement these practices.

Light, with Missouri Soybeans said farmers didn’t join the pilot program unless implementing cover crops or no-till fit with needs.

“The farmers aren’t jumping to plant a bunch of cover crops and make these changes on their acres unless it fits their needs exactly where they were going to be doing this work anyways, because the price just isn’t there,” Light said.

Hemme agreed.

“More consistent and better yields and all that is going to pay way better than a carbon credit,” Hemme said.

At this point, he’s not sure what the price of a carbon credit would have to be for it to serve as an effective practice-change motivator.

“But, it would have to be a lot more than what they are now,” Hemme said. “I think there’s potential there, I just don’t think it’s there yet.”

Hemme said that in addition to a higher payment farmers need to have guidance available to them in order to implement these practices.

“If guys have a bad experience with cover crops, they’ll never plant one again,” Hemme said. “Guys have to have the knowledge and somebody to help them with the process of getting started. Because it’s a whole different world of farming than your conventional way of doing it.”

The added layer of carbon credit can also affect some necessary farming decisions.

For example, in a very wet year, a flooded field can benefit from tillage to help dry out the soil. But–tilling that field would mean Hemme would lose the carbon credit.

“There’s always that nagging feeling in the back of your mind that you don’t want to screw up the carbon credit, so it might keep you from doing a practice that might be necessary for a situation,” Hemme said. “A farmer has got to make a decision on what’s best for him, not what’s best for a carbon credit.”

The ultimate goal of a carbon credit is to sequester more carbon out of the atmosphere and encourage regenerative soil practices.

The current market might not be perfect as it is, or able to be the sole thing that motivates people to these practices. But, Cameron-Harp said a carbon credit might be the tipping point.

“There may be producers that are right near the cusp of cover crops being worthwhile or not,” Cameron-Harp said. “Well, in those cases, these carbon credit payments are the thing which can tip the scale, even though they’re small. That is still additional carbon being sequestered in soil that wouldn’t have been otherwise.”

Hemme isn’t sure if he’ll renew a carbon contract. The added computer work outweighs a potential carbon credit payment.

“I don’t know,” He laughed. “It almost isn’t worth the hassle–I don’t know.”

Carbon contract or not, Hemme plans to continue implementing his added cover crop. Whether he sells it or not, he’s sequestering carbon.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.