Landon Laird: Remembering Kansas City’s First Film Critic A Very Kind Hollywood Correspondent

Published March 9th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Landon Laird on the set of “The Buccaneer” with Cecil B. DeMille and, on right, Louise Campbell and Margot Grahame in 1937. (Courtesy | Jackson County Historical Society)Spencer Tracy was missing.

“Tracy!” said Joan Crawford, pacing around the film studio. “Tracy! Where in heaven’s name is Tracy?”

Tracy was right there, “in conversation with a friend,” as the moment was described in a September 1937 Kansas City Star article bearing a Hollywood dateline.

“Shall we rehearse this scene again for Miss Crawford, or should we take the picture?” Tracy asked in mock exasperation.

This off-camera interlude included three film industry veterans with Kansas City connections.

Tracy, as a teenager in 1917, had spent a semester at Rockhurst High School.

Crawford, at about the same time, then known as Billie Cassin, had financed her fledging dancing career as a downtown Kansas City department store clerk.

Witnessing their breezy exchange was Landon Laird of the Star, likely the newspaper’s first film critic, who included it in his brief story describing the filming of a movie named “Mannequin.”

The “picture” Tracy had been referring to, meanwhile, may have been the photograph then being taken of himself and Laird, the latter holding a small notebook and scribbling notes.

Today that photo is one of about 30 depicting Laird with movie stars archived by the Jackson County Historical Society.

Among the industry figures Laird posed with during visits to California film studios in 1937 and 1938 were Fred Astaire, John Barrymore, Claudette Colbert, Cecil B. DeMille, Carole Lombard, Edward G. Robinson and Anna May Wong.

Sometimes Laird hammed it up. In one photo, W.C. Fields pretends to wave him away from a table of liquor.

In another, Laird sits just off-camera, a few feet from where Ray Milland was filming a scene.

In still another, Laird appears on camera, in a 1941 western, “Rodeo Rhythm,” filmed in Kansas City. (IMBd today notes Laird’s sole acting credit as “lawyer.”)

The pictures are part of the papers of Mary Graham Minor-Laird, donated to the Jackson County Historical Society in 2001 as part of its Women’s History Collection.

Today, just before the Academy Awards, they offer a glimpse of Hollywood publicity practices of the time.

But the photos – along with the collection’s scrapbooks, news clippings, hotel receipts, correspondence and related ephemera – also offer evidence of how the country’s vast entertainment industry operated in the 1930s. Hollywood offered welcome distractions during the Great Depression. And Laird and his wife, Mary Graham Minor-Laird, a Kansas City dancer, found footholds within it.

One professional handicap Laird had to overcome as a critic — many agreed years later — was that he was too nice to pan bad movies.

“It is interesting to note that Laird was criticized by a few because he was not critical enough in his writings,” the Star conceded in Laird’s 1970 obituary.

But to his many readers that proved to be part of Laird’s appeal.

Adjunct to the Industry

The 30 archived pictures appear to have been taken by film studio photographers since, as in the same September 1937 story, Laird thanked several industry executives who had arranged his visits.

He also acknowledged the stars who had posed with him.

“It would be an ungrateful guest who left a party and failed to thank his hosts for the pleasure he had enjoyed,” he wrote.

But it was Laird’s hosts who had reason to be grateful.

“Local critics had a lot more power and sway than they do now,” said Gerald R. Butters Jr., a Kansas City, Kansas, native who in 2007 published “Banned in Kansas: Motion Picture Censorship, 1915-1966,” detailing the state’s film regulatory board, established just before World War I.

“Today, because of social media, you get opinions of films from a thousand different people,” said Butters, a history professor at Aurora University, near Chicago.

“But back then we were a newspaper culture, and newspaper critics could make or break a movie.”

Laird accepted the access the film studios were eager to give him, added Robert W. Butler, the Star’s principal film critic from 1978 through 2011.

“In the years before television, there was a huge publicity effort to get audiences pumped up for a movie,” Butler said.

“During the 1930s a movie might get a mention on the radio, but that didn’t have the power of a real, live movie star.”

That power could be used in several ways. Butler said. The actors could come to Kansas City — where many film studios kept offices in the “Film Row” district, in or near the current Crossroads area — and make personal appearances.

“I recall back in the 1970s, during the Show-A-Rama (Kansas City film industry) conventions, a lot of the old-timers talking about the big movie stars who would come in and occasionally misbehave,” Butler said.

“But most of the time these stars would be on their best behavior because these appearances were written into their contracts. There would be ads in the paper that would say, ‘Come out tonight and see such and such at this or that particular theater.’

“It might not be Clark Gable, but maybe somebody like Anna May Wong.”

(Wong made at least one personal appearance at Kansas City’s Newman Theatre, in 1925.)

Laird, Butler added, may have been part of such promotions.

And then, at least twice in 1937 and 1938, Laird traveled to the California studios.

“Laird was an adjunct to the industry, and everybody had a part to play in the publicity machine,” Butler said.

“So, readers of the Star would see Laird out schmoozing with the stars and talking up their new movies.”

(For the record, Butler added, he didn’t pose with performers during his years as a film critic.)

“I would have been appalled,” he said.

He never asked for autographs either, Butler added – or, almost never.

”I have to say that once, on behalf of my pre-adolescent daughter, I asked Kiefer Sutherland for a signed picture,” Butler said.

“I’m sure I will spend some time in purgatory for that, but my daughter loved Kiefer in ‘The Lost Boys.’ “

Impressions on the Youthful Mind

Laird joined the Star in 1914, working on the paper’s sports and features desks.

That was during the Progressive Era, when many considered the country’s growing film industry disreputable and sought to regulate it.

Concerned citizens and public officials fretted over the ill-ventilated storefronts the films often were shown in, but also about the films themselves.

Chicago had approved one of the country’s first municipal censorship ordinances in 1907, when nickelodeons began appearing in the nation’s larger cities. The establishments charged customers five cents to watch short projected films as well as vaudeville acts.

The Chicago censorship directive compelled the city’s police chief to issue permits to film exhibitors and to order cuts in films considered salacious.

Three years later Kansas City established the country’s first public welfare board.

Through its “Recreation Department,” the board at first regulated public dance halls.

Then its officers eyed the sudden growth of movie theaters.

By 1912, according to their “careful and conservative estimate,” an average weekly attendance of 449,064 customers patronized the city’s 81 movie theaters, meaning that an audience approximately one and one-half times the city’s total population attended a movie every seven days.

They then turned their attention to the films being shown there.

Under city ordinance, local film exchanges had to submit weekly lists of films being shown. Censors could request to screen them and if exhibitors pushed back, the city could request court injunctions to ensure compliance.

By May 1914 city censors had cut more than 26,000 feet of film. In their first full year, they viewed 300 films, rejecting 13 and ordering edits in 170 others.

“The large number of young people attending these picture shows make it an important question as to what kind of pictures are shown and the impressions made on the youthful mind,” according to the “Social Prospectus of Kansas City, Missouri,” published by the welfare board.

Similar concerns motivated Kansas lawmakers, who established the country’s second state censorship board, first funded in 1915.

As detailed in Butters’ 2007 book, the alleged outrages of the film industry were several.

Some of the pictures portrayed the use of alcohol. Kansas, meanwhile, had been the first state to attach a Prohibition amendment to its constitution in 1880.

The behavior depicted in other films could be suggested by their titles: ”The Janitor’s Wife’s Temptation,” “Damaged Goods,” “The House of Bondage.”

In the face of this, some Kansas community leaders become culture warriors.

“It is better that our people know nothing of the wicked ways of the world,” said Festus Foster, a Topeka minister and member of the state’s first board of censors.

Perhaps even more upsetting for residents of the state’s many farming communities was how so many of these films depicted scenarios occurring in urban centers. The fear among some rural voters of losing their children to the cities, Butters wrote, contributed to the 1914 election of Arthur Capper, Topeka newspaper publisher, as governor.

In response, several separate groups — religious leaders, as well as progressives — joined together to support state regulation of films.

“Many progressives didn’t want so much to ban movies but to see more movies being used for educational purposes,” Butters said.

“And there were also those who were opposed to what they considered modernism, which might corrupt society.”

The early 1920s scandals involving film stars such as Fatty Arbuckle (arrested in 1921 on rape and murder charges) and Mabel Normand (implicated in the 1922 murder of film director and actor William Desmond Taylor) further demonstrated to some the need for regulation.

Ultimately, seven states would establish censorship boards.

The Kansas board lasted through the 1960s, despite U.S. Supreme Court decisions that appeared to sanction further First Amendment freedoms for films, Butters wrote. Censors, however, continued to screen movies in a KCK fire station.

The board finally shut down in 1966, Butters wrote.

In Kansas City, Missouri, such regulation began to decline by 1918, as rival political machines skirmished over available welfare board seats.

Kansas City Star editors, meanwhile, named Laird drama and motion picture critic in 1924.

Jobs that Needed Doing

One possible problem – Laird was just too nice a guy.

“A stinker of a show he would criticize mildly, unless it was obscene,” former Star sports editor Ernie Mehl said upon Laird’s 1970 death.

”Then he would take out after it.”

However amiable he was as a critic, some films still underwhelmed Laird. A 1938 movie entitled “Freshman Year,” which he had seen being filmed in Hollywood, might be one of those, Laird conceded.

“How a script writer could turn out a composition of this kind we cannot understand,” he wrote, before adding how, despite that, “the action steps along and there are several fast song and dance numbers.”

Not only that, Laird added, during the movie’s scheduled run at the downtown Tower Theatre, “Benny Goodman and his orchestra are up on the stage, so why worry about anything else?”

Butler, who joined the Star staff in 1970, never met Laird but heard about him.

“John Haskins, the papers’ music critic, told me how Laird, if he was desperate to find something good to say about a movie or play, would always say ‘They had a job to do and they did it.’

“It was his go-to line.”

In 1929 Laird introduced his “About Town” feature, which 10 years later would begin appearing daily in The Kansas City Times, the Star’s morning edition.

In the column, Laird routinely identified himself as “your correspondent” and addressed his readers in a self-deprecating manner.

The column eschewed pontification for street-level reporting, with the voices being quoted often belonging to nightclub patrons or theater managers.

Since he wrote for the morning paper, Laird’s day likely would begin in the afternoon, when he began patrolling the restaurants and theaters found along or near Baltimore Avenue between 11th and 14th streets.

The next morning, homebound readers of the Times would receive reliable coordinates on what constituted Kansas City after dark.

During World War II, Laird’s columns often would be devoted to dispatches from the front, as described in letters from service members.

Then there was the day in 1945 when Laird followed two barbershop quartets to a Topeka hospital and watched them entertain injured service members.

“About 6 o’clock … wounded men began to fill the seats in front the stage in the recreation hall. A boy with one eye gone chose a front row chair. Another boy placed an arm in a cast on the back of the chair in front of him. One young father, his wife at his side, rested his leg in a cast on the seat of an adjoining chair. On his good knee he held a curly-haired little girl, about a year old. Occasionally some other wounded soldier, in the pajama-like uniform of the patients, would pick up the baby and carry it around the hall.”

Just as he was a friend to the film industry, Laird likely was an asset to the Kansas City Star and Times as a person whom readers could identify with, as opposed to the distant, monolithic institution many may have considered the newspapers to be.

“He was relatable,” said Monroe Dodd, a former editor of the Times and Star, and the author of the 2006 book, “The Star & the City,” a history of the publications.

“He strikes me as a bon vivant, but one who didn’t take it to extremes.”

The daily “About Town” column, Dodd added, resembled “Goings On About Town,” the chatty guide to show openings or jazz club attractions that could be found in the “New Yorker” magazine.

“He was a shoe-leather reporter, often going from place to place, walking up and down Baltimore Avenue,” Dodd said.

Just as important, he added, seemed to be Laird’s authentic regard for those who spoke with him.

“He would not excoriate people,” Dodd said. “He wouldn’t trick them into saying things. It wasn’t the kind of thing you would see in the London tabloids.

“He was always positive toward people, and people can’t help but like that.”

Over time, Laird’s private life became public knowledge. His 1947 marriage to Mary Graham Minor, a former Kansas City dancer, was front page news in the Star.

Entertainment figures, meanwhile, especially admired Laird.

“He was loved by all people in show business, people like Helen Hayes and Henry Fonda and Ethel Waters,” John Antonello, Municipal Auditorium director, said in 1970.

Evidence of that survives today in the Jackson County Historical Society archives.

William Demarest, the veteran character actor, signed a photo for Laird, saluting “My pal of years ago, who always gave me a good notice.”

When Laird’s mother died in 1936, another Kansas City film industry figure wrote him a condolence note on pale blue personalized stationery, the name “Jean” imprinted in white letters near the top-left corner.

“There is nothing anyone could say which would in any way lessen your heartache and grief, but I wanted you to know that someone here in California was thinking of you,” wrote Jean Harlow, who would die less than a year later, at age 26.

Laird’s “About Town” column would appear an estimated 7,400 times before its last installment, published May 11, 1967.

In the months before Laird’s retirement the organizations that held dinners in his honor included Rockhurst College, the Jewish Federation of Kansas City, and Golden Gloves of Kansas City.

Golden Gloves, which organized an annual tournament for which Laird served as ringside timekeeper for 20 years, likely was another organization that benefited from its association with Laird, wrote Star sports columnist Joe McGuff in 1968.

“Although amateur boxing has been well administered, its name has been tarnished to a certain extent by the evils of pro boxing,” McGuff wrote in advance of that year’s tournament, which had been dedicated to Laird.

“The recognition accorded Laird is richly deserved.”

McGuff would be among the Star’s prominent figures who served as pallbearers at Laird’s 1970 funeral, Dodd added.

“Most of the top editors and columnists at the paper carried his casket,” Dodd said.

Laird’s memory endures today because of his widow.

Two Thumbs Up for ‘Mannequin’

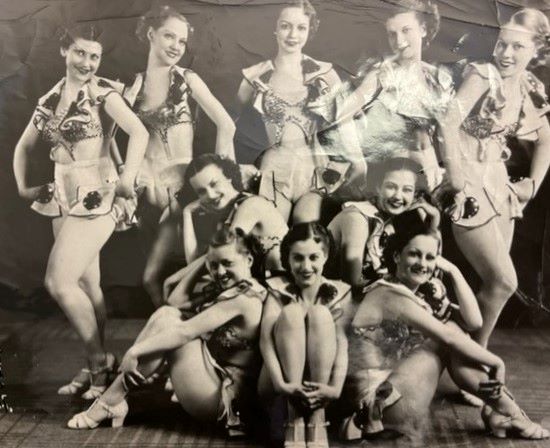

In several large scrapbooks whose covers she made busy with stickers bearing the names of hotels in Ocala, Florida; Anderson, Indiana, and Mason City, Iowa, Mary Graham Minor archived her dancing career.

That began at Kansas City’s East High School, where she was a member of the first graduating class in 1930.

By 1934 she — billed as an “Unusual High Kick Dancer” — was a member of bandleader Paul Cholet’s Cocoanut Grove Revue chorus line, traveling across Depression-era America when some larger theaters still offered live entertainment between films.

“Mary Graham Minor, in a high-kick number, drew dancing honors,” wrote the Macon, Georgia, critic.

Back in Kansas City, Minor served as a member of the “Tower Adorables,” the dancers employed at the downtown Tower Theatre.

If her scrapbooks today document the admiration of heartland critics, they also testify to the volatility of the entertainment life, especially during the Depression years.

Preserved there is the one-week termination notice she received from the Tower manager on Feb. 22, 1935.

Also included is the telegram from Detroit that Minor received on Dec. 12, 1936, delivered to the Tower, where she had apparently been re-hired.

“Have work for five girls,” it read. “Have to know immediately.”

Sometimes shows would simply shut down on the same days patrons already had paid to see them.

In January 1942, when the 12-member Mary Graham Minor Girls dance troupe was preparing to begin their stage show after the matinee feature, the management of the Mainstreet Theater at 1400 Main St. announced that customers could pick up their admission fee refunds on their way out.

By 1947, when she married Laird, Minor had left the stage for a desk at the Jackson County probate court, where she represented The Missouri Abstract Co.

She later served as a local examiner for the Chicago Title Insurance Co., from which she retired in 1978.

She donated her show business files to the Jackson County Historical Society in 2001.

“I’ve been wanting to find a home for these things for ever so long,” Minor-Laird told a Star reporter.

“I thought they would all just go to the dumpster. Now they won’t.”

The files included approximately 30 photos of film stars posing with her late husband, but also a much greater number of postcards, thank-you notes, telegrams and letters sent to him by admirers over several decades.

“He loved all kinds of people, and he was born for newspaper work,” said Minor-Laird, who died in 2009 at age 96.

For her husband, there were no people like show people.

Some five months after observing the filming of “Mannequin,” a movie that may not come to mind today when considering the careers of Joan Crawford or Spencer Tracy, Laird published his opinion of their performances.

“The two are in the top rank of Hollywood stars at present, and it is a happy pairing to look at in a ‘home town,’ prideful aspect, which brings them to the Midland theater this week,” Laird wrote in 1938.

“‘Mannequin’ is a good picture, far better than Miss Crawford’s immediately previous venture, ‘The Bride Wore Red,’ “ Laird wrote, further adding that Crawford “plays her part well, on the whole, and Mr. Tracy makes his every moment before the camera count, a talent he has possessed, and upon which he has capitalized, for a long time.”

Film critics employed by larger newspapers than the Star, Butler said, often didn’t have to face the challenge of navigating subjective opinion with objective observation — not to mention running the risk of being considered an ungrateful guest.

“For Laird,” Butler added, “keeping the critic and the reporter separate in his head had to be nearly impossible.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author. He is serving as president of the Jackson County Historical Society.