Mending Our Broken Heart: Denver’s Turnaround Grew From Housing

Published September 28th, 2022 at 11:30 AM

“Downtown KC: Mending Our Broken Heart,” was a groundbreaking series originally published by The Kansas City Star 20 years ago this month.

It was written by former staffers Jeffrey Spivak, Kevin Collison and Steve Paul, with photographs by Rich Suggs. It was edited by former deputy national editor Keith Chrostowski.

CityScene KC thanks The Kansas City Star and Mike Fannin, its president and editor, for granting permission to republish this report.

While The Star retained the text of “Mending Our Broken Heart,” the original photos and graphics were unavailable. Photos of that missing material from a reprint of the series were used as much as possible.

DENVER – A decade ago, Denver Mayor Wellington Webb commanded: Let there be downtown housing.

And it has been good.

Since Webb’s pronouncement, lofts, apartments and condominiums have sprouted, pushing downtown’s population to more than 10,000, with loads more residents on the way.

In turn, dozens of new restaurants, cafes and trendy shops have opened and Starbucks-sipping, cell-phoning pedestrians – many of them younger adults – crowd manicured sidewalks.

Webb took office in 1991 and inherited a downtown of half-empty office towers. What made tourists hesitate on their way to the mountains was the surplus of T-shirt shops.

His first call was to convene a three-day summit at a hotel ballroom to hear what the public and experts had to say. Then he acted.

Out went a plan for a shopping center. Instead there would be housing – and all the city could do to support it.

“The mayor said retail doesn’t lead, it follows,” said Jennifer T. Moulton, the city planning and community development director.

“We needed a 24-hour downtown, and we had to compete with suburban office developments because downtown was not an interesting place to be.”

The Denver Dry Goods Store, an empty landmark in the heart of downtown, was the first target.

The mayor ordered the urban renewal agency to turn it into a residential and office project. He told the city-funded convention and visitors bureau to become an anchor tenant.

Webb then prodded the Downtown Denver Partnership, an organization of property owners. The 45-year-old business group had never done housing before.

The city and the partnership set up a Center City Housing Support Office. It gave developers market information, listed an inventory of buildings and at a time when local lenders were skittish, offered financial help.

Tax-exempt bonds issued by the city through a federal program previously used for industrial projects became a great tool for developers. Historic tax credits helped, too.

Webb’s effort came at the right time. Plenty of older office and warehouse buildings were available. And a market for urban living was emerging.

“Empty nesters were looking for something other than a big house, and 20-somethings didn’t want to live in the suburbs,” Moulton said.

Webb also steered big public investments toward downtown. But the idea was not to do glitzy projects for their own sake, but to create a downtown where people wanted to live.

Sports facilities, performing arts centers, libraries and art museums all went downtown. The best-known is Coors Field, the home of the Colorado Rockies.

The baseball park, which opened in 1995, is in LoDo, short for Lower Downtown Historic District. Its turn-of-the-century warehouses are now home to many new residents.

The ballpark shows just how fervently Denver thinks housing is the key.

U.S Sen. John Hickenlooper of Colorado was running the Wynkoop microbrewery when he was interviewed for the “Mending Our Broken Heart” series in 2002.

At first, developers such as John Hickenlooper, the owner of the Wynkoop microbrewery, a LoDo institution, opposed the ballpark. They thought it would ruin the residential atmosphere.

He has since changed his mind.

“Baseball, unlike football or basketball, is a big family sport,” he said. “It brought all these people downtown who hadn’t been before.”

Moulton went further.

“Baseball attracts housing,” she said. “It’s a romantic sport and family friendly. People feel romantic about living next to a ballpark.”

To make downtown feel safe and clean, the city set up a new downtown police precinct, and property owners taxed themselves to establish a business improvement district so obsessive it regularly power washes the streets.

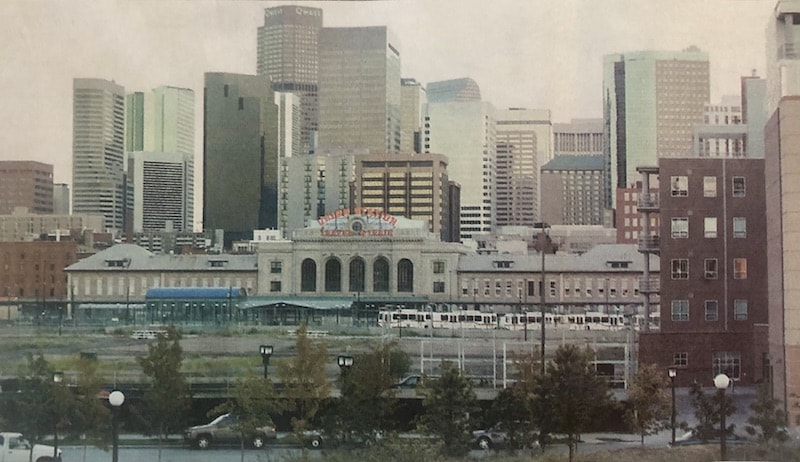

Major public works projects primed the pump for more housing. Old street viaducts that encumbered LoDo were razed. Land behind Union Station was opened for new development when most of the train tracks were removed.

To keep people moving, the transit authority set up a free bus shuttle running the length of downtown. It stops at corners every five minutes.

“We saw a real commitment on the city’s part to downtown, to make it a viable community,” said Mark Smith, president of East West Partners. His firm is building 3,500 condos and apartments in the Central Platte Valley, behind Union Station.

“I predict there will be 25,000 people living downtown in 10 years,” Smith said. “It’s matured to the point where there’s lots of things to do. It’s like a neighborhood in Manhattan, a SoHo.”

Bill Falkenberg moved with his parents from Kansas City to Denver in 1939. Last December, he and his wife moved from their big house where they raised three children into a spacious fourth floor loft in LoDo.

“We love it,” the retired builder said.

He was relaxing in sandals, khakis and a polo shirt in the living room of his condo. Timber columns revealed its industrial heritage, and a louvered window looked onto a deck with views of brick warehouses.

“We came down for the excitement and the convenience,” he said. “There is a lot of variety here. A lot of single people, young marrieds, old marrieds. A lot of people also use these condos as a second home.”

Marilee A. Utter and her husband bought a condo in a former John Deere Co. warehouse. It’s richly decorated with contemporary art and includes a deck with a spectacular skyline view.

Utter has an office in her home and walks to her health club, coffee shop and other destinations. For groceries, she drives to a supermarket about a half mile away.

“People complain about it,” she said, “but tell me how many people in America don’t get in their car to go grocery shopping?”

She praised the feeling of community in LoDo. A family with three young daughters recently moved in across the hall. They’d come from London.

The LoDo District became a popular place to live and play after the opening of Coors Field. (Photo from LoDo District website)

Numbers confirm the wisdom of Webb’s vision.

There are now 5,278 residences in downtown, 55 percent of them condos and 45 percent apartments, according to the Center City Housing Support Office. And 1,932 units are under construction with 2,882 more planned.

The 2000 Census reported 10,169 persons lived downtown, up 28.4 percent from 1990.

The number of restaurants has grown from 203 in 1995 to 256 last year.

Hickenlooper said condos that sold for $60 per square foot in 1992 are now selling for $250 per square foot. Utter said her 2,500-square-foot condo was recently reappraised at $875,000. She paid $375,000 for it eight years ago.

Rents have increased from an average of $620 per month in 1992, to $866 per month last year, according to a Downtown Denver Partnership survey.

These days, local lenders chase downtown housing developers, said James G. Fitzpatrick III, executive president of Corum Real Estate Group.

“Lenders are looking for good investment opportunities, and downtown is looked at as a good investment opportunity,” he said. “It’s not a fad.”

The benefits also have created great buzz for the city. T-shirt shops still abound, but downtown is now a destination aside from the mountains.

Said downtown developer Dana Crawford: “We have almost on a weekly basis somebody coming from other communities in the United States and sometimes Europe to try to figure out what happened here.”