Campus Protests Over War in Gaza Echo Anti-Apartheid Era Learning the Lessons of History

Published May 9th, 2024 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Students at the University of Kansas set up an encampment in front of Fraser Hall last week to protest the war in Gaza and and call for university disinvestment in Israel. (Cami Koons | Flatland)At the University of Missouri-Columbia, 41 students were arrested and jailed.

They let their bodies go limp, putting civil disobedience training to use by making it difficult to be hauled off by sheriff’s deputies. The students were strip searched. They sat overnight in the Boone County jail.

The next day, several students chose to remain in jail. They began a hunger strike.

All were charged with trespassing — on their own college campus.

The Mizzou students had refused the administration’s orders to vacate the plywood and cardboard shacks of the shantytown that they’d erected months before on the iconic Francis Quadrangle.

They had held their ground there for five months, rebuilding when campus officials tore the encampments down.

Determined, the students wanted the university to divest its investment holdings, to take a moral stand with its endowments.

Sound familiar?

Those MU arrests happened in February 1987.

Campus Protests: Then and Now

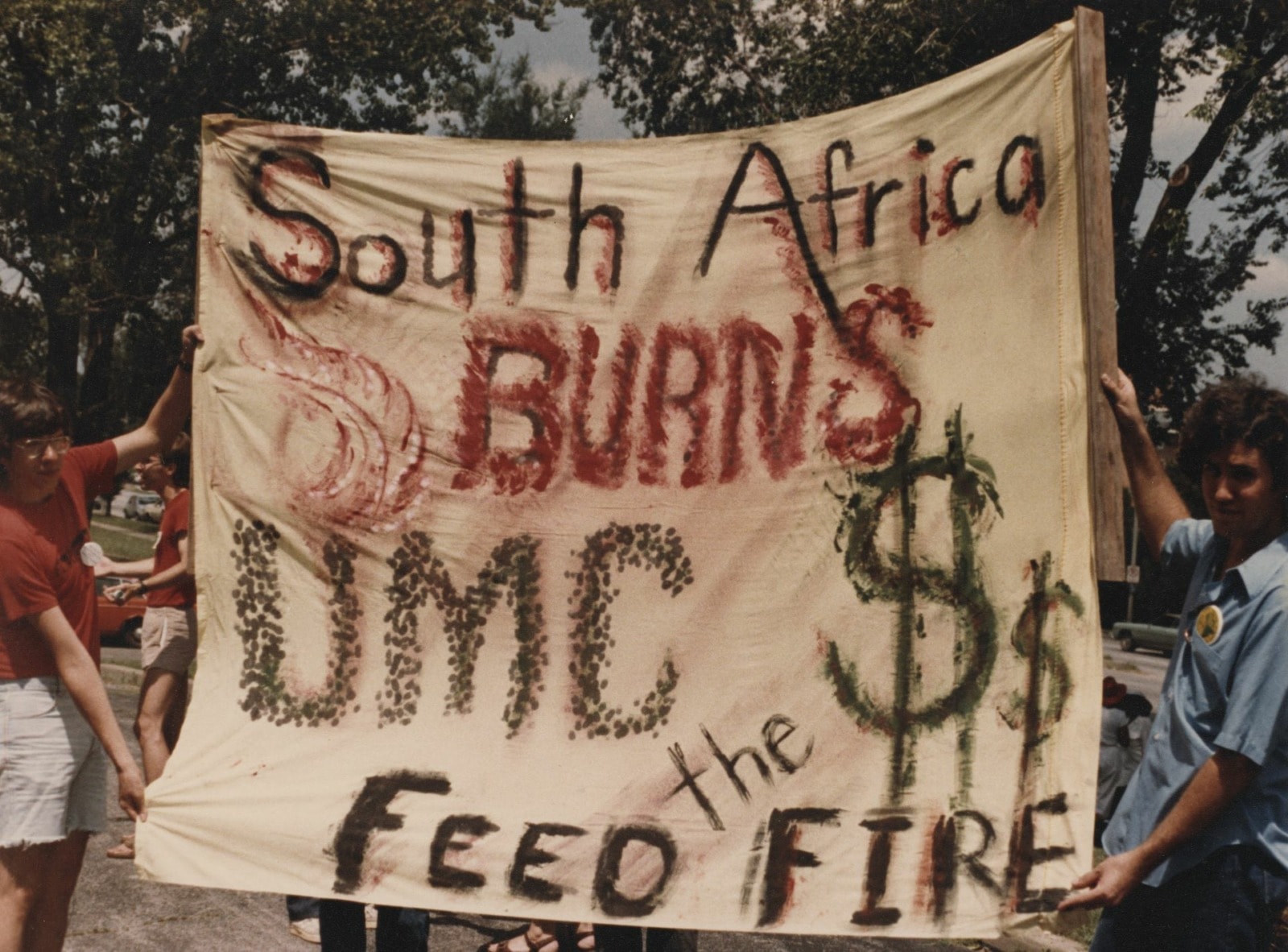

In the mid-1980s, normally bucolic Midwestern campuses played a role in forcing universities to divest millions of dollars from supporting the racist apartheid government of South Africa.

They did so in more sustained ways than what has been allowed for by area student protesters in 2024, at least so far.

Tuesday afternoon, Lawrence police came to the University of Kansas campus and confiscated the tents that students had erected as part of their peaceful protest. They’re asking for the divestment of university funds from supporting Israel in its war against Hamas in Gaza.

Later, police returned and took water, food and other supplies the students had set up for the “Solidarity Encampment.”

“Disclose. Divest. We will not stop. We will not rest,” the students chanted as the police loaded the items. Students filmed the scene on cell phones.

Kathryn Benson was one of the MU students arrested in 1987. Like her former peers, she’s keenly interested in how students today are being treated by campus officials, and how they are perceived by the general public.

On Monday, 13 conversative federal judges issued a statement that they won’t hire law students or undergraduates from Columbia University, the recent scene of pitched protests against the war in Gaza, saying that the institution had become “an incubator of bigotry.”

Last fall, several CEOs issued similar threats.

“It’s truly disturbing that people are seeking to stifle our right to protest and giving repercussions,” said Benson, now a public defender in Fulton, Missouri.

Benson faced no long-term backlash for her anti-apartheid activism, she said. The worst that she endured was racist hate mail.

In fact, the Mizzou students were able to turn their arrests into an advantage.

“We were hoping to have enough people arrested that it would overwhelm the county jail and cause them to have to house other inmates elsewhere,” said Benson. “It was to put pressure on the university to not arrest people.”

Benson’s father is J. Kenneth Benson, a now retired, professor emeritus in the MU sociology department.

In 1970s, he had also gotten crosswise with the university for cancelling classes so students-then could protest the Vietnam War.

During the Vietnam War, students began to have friends and relatives who were killed overseas, sparking activism. Protests flared after the Ohio National Guard fired into student protesters at Kent State University, killing four students and injuring nine more.

Benson, like others who took part in the 1980s, sees the similarities and differences between student activism movements through the decades.

In the past, it wasn’t as if U.S. campuses were filled with South African students who could speak from experience about the issue. It was largely white, often middle-class students who merely learned about the plight of Black South Africans and were mortified. Other efforts were led by Black college students, seeking to help Black South Africans gain equal treatment.

In contrast, today’s university student populations are much more diverse. Protesting students can often speak from their firsthand experiences of living in the Middle East. Many have family abroad or hold an affinity due to their Muslim faith.

They expect the values of the universities where they are enrolled to respect their backgrounds, and to show it through socially conscious investments.

In some ways, the issues today feel more complicated for students and administrations to navigate, said several former student activists.

“Obviously, there are issues on both sides of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and things that can be done on both sides to fix it.,” Benson said. “But apartheid was just clearly wrong.”

Students at MU, the University of Kansas, the University of Missouri-Kansas City are demanding transparency of university investments, divestment, cutting links to the U.S. military and in general, separation from support that could be viewed as detrimental to the human rights of Palestinians.

Both Missouri and Kansas have passed laws in recent years prohibiting boycotts, divestment or sanctions against Israel, a fact that is cited by university officials in both states.

At KU, final exams are being given this week.

Last Friday evening, students had left the encampment set up outside Fraser Hall, packing up for the weekend.

At UMKC, recent rains have started to rinse away the long lists of names of Palestinians who have died, painstakingly written in colorful chalk by protesting students on sidewalks.

On Tuesday, Israeli forces seized control of the Rafah border crossing linking Gaza with Egypt, a key humanitarian route.

Israeli Defense Forces began retaliating for the killing that Hamas orchestrated of Israelis on Oct. 7. Then, 1,200 Israelis and foreigners were killed, and more than 240 hostages were captured.

Since then, nearly 35,000 Palestinians have been killed, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, many of them women and children.

Nationwide and locally, campus organizing began soon after.

Students say they are girded for the long haul.

UMKC Students for Justice in Palestine was founded by Yara Salamed, a law school student.

She’s lived in the West Bank with her family and experienced the feeling of being constantly assumed to be antisemitic and a lesser person.

“The Palestinians in Gaza, and in the West Bank, under the Israeli government, they have absolutely no rights at all,” she said. “Even the Palestinians who have Israeli citizenship are like second-class citizens.”

A key motto of the UMKC group: “We will not stop. We will not rest.”

Mortar board toppers that UMKC students can wear at their upcoming graduation ceremonies are being made available now, as they were at the fall commencement.

“Roos For Palestine,” is displayed in the red, black and green of the Palestinian flag.

The more recent campus sit-ins, while widely covered by local media, are merely the group’s latest actions.

At UMKC, the student group began leading teach-ins last fall, participating on panels and holding readings on social media from books like “The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017” by Rashid Khalidi.

An outdoor protest in late April at UMKC drew several hundred students and the attention of administrators. At one point, campus security tried to rip down tents.

Of the many speakers that day, one summed up a key stand: “Within in our lifetime, we will see a free Palestine.”

College Activism Sparks a Career

Patience and perseverance are key lessons linking protests now with those of the past.

The college students who began the anti-apartheid efforts in the late 1970s were no longer enrolled when their demands were met.

They had long since graduated and moved on to their careers by the time the state of Missouri divested from South Africa in 1987 and asked universities to do the same, a request that was completed by January 1993.

By then, the minority-white government of South African apartheid had also fallen, famously dismantled by negotiations between Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk. The men were jointly awarded the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize.

Former students who took part in those earlier protests remember their activism as key to paths that they later chose.

Benson was the MU student chosen to represent the group at trial, months after the arrests. She remembers being impressed with the pro bono legal representation that she had through the American Civil Liberties Union.

She was found not guilty in a bench trial.

“It very much had a lot to do with not only going to law school, but becoming a public defender,” she said. “I was in private practice too, and I was involved most heavily with criminal defense.”

Several other former protesters are university professors. Another is a technology executive. And another, initially a journalist, later became a spokesperson for the Kansas American Civil Liberties Union Foundation.

Mark McCormick was a KU student in the late 1980s, protesting apartheid and other issues on campus.

“I remember thinking afterwards that I had a voice that I didn’t know that I had,” said the former deputy director for strategic initiatives at the Kansas ACLU.

There were times when word got out that police were coming to clear protests on campus. And McCormick remembers being vigilant that no one would get hurt, taking the microphone to ask for calm.

Other instances had him in meetings with the then-chancellor, trying to negotiate.

“I just feel like I was lucky that I had that experience,” he said of his time protesting university investments that had supported South African apartheid, and other civil rights issues. “You get to explore who you are going to be, what you believe in.”

As a KU student, McCormick took a class on South African history.

He been reading “Kaffir Boy, An Autobiography, the True Story of a Black Youth’s Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa.”

But in class, he learned more.

He studied how South Africans had to carry identity papers and that tests were used, such as seeing if a comb would stick in a person’s hair — the offensive implication being that someone considered Black would have curlier, thicker hair.

The KU students formed their own group, Black Men of Today, believing that the Black Student Union was too averse to conflict.

Issues included standing up for a student who was allegedly sexually assaulted at a fraternity, challenging the administration for how it handled the case.

They didn’t erect shantytowns like at Mizzou. Instead, they targeted the university’s contracts with Coca-Cola, which did business in South Africa.

“The real thing is a real shame,” was the slogan the Black students used.

The students were adept at calling local media from Lawrence and Kansas City to cover their protests. At one point, that drew the attention of three Black executives from Coke who came to campus and tried to dissuade the students.

They weren’t successful.

By then, 1989-90, anti-apartheid movements were seeing an impact with corporations. Pepsi had left South Africa.

Coke had sold its factory to Black South Africans, which McCormick said the executives spoke about it as if it was a noble action.

But the students had done further research.

They had flyers ready, showing a tall glass of Coke, with dead bodies drawn at the bottom of the glass.

“They sold the syrup company to white South Africans just so they could take over the market because their competitors honored the boycott and left,” he said. “So even if you owned the Coke company, you couldn’t do anything without the whites. It was just a plan so that they could dominate the market when everyone else left.”

He doesn’t believe that their efforts influenced the administration to divest.

But the attention did affect other students.

After he graduated, a member of the Black Men of Today was elected student body president.

Teaching Moments

A double-digit tuition hike sparked the anti-apartheid student activism at Mizzou.

Student government leaders were alarmed. They felt that the rising fees were too large of a burden on many students, said Doug Liljegren who was the Missouri Student Association President in 1978.

The curators had been working with the legislature, which was trying to balance state budgets.

“We were concerned that our students were not being heard,” said Liljegren, now of Leawood.

The students began researching the university’s investments, trying to find out where the money was being placed.

“We also found that they were heavily invested in tobacco and other companies that had a negative health impact on students,” he said. “So, it was a surprise of where they were invested.”

Liljegren signed the letter to the curators asking for change.

The letter reported that the university had investments in 54 companies doing business in South Africa.

“We presented an alternate budget to the board, suggesting that they could raise the funds in other ways,” he said.

The students suggested real estate investments.

Their plan wasn’t adopted, but the tuition hike was eventually trimmed back, he said.

Much of this information is contained in the papers of Carla Weitzel, covering student activism at MU between 1970 and 1999.

Weitzel was a leader of the student-led anti-apartheid movement years later, in the late 1980s, when Benson was also student.

Weitzel is remembered as a brave, vocal opponent of apartheid.

She died in 2000. And her husband later donated her archives to the State Historical Society of Missouri.

Liljegren donated his archives to another collection, the African Activist Archive, which is based at Michigan State University.

By the late 1980s, protests had spread to campuses nationwide, much like what is occurring now.

Some of the former student activists said that university officials seem far less tolerant, less willing to make deals with students now, especially about allowing encampments to be constructed.

Barbara G. Brents is a professor of sociology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

In the 1980s, she was a Park Hill High School graduate and among the students arrested at MU for refusing to leave the anti-apartheid tents.

“At Missouri, we didn’t have all that many tents until the police started threatening to remove them,” Brents said. “And then, more people started occupying.”

Rallies could draw several hundred students and supportive faculty.

At one point, 17 students were arrested, charged with trespassing. The charges were later dropped.

The largest group of arrests happened later, when a deal that had been made with then-Chancellor Barbara Uehling expired. Uehling had agreed to let the students keep the structures in place until January 1987.

By February, an interim chancellor was in place. Duane Stuckey ordered the tents removed.

The students rebuilt them.

That’s when the arrests of the 41 students, Brents and Benson included, began.

Although the latest calls for divestment from Israel feel similar, the issue in the past was less controversial.

“Nobody thought apartheid in South Africa was a good thing,” Brents said. “It was really just a debate over what’s the best way to change things and should you be involved in another country, that sort of thing.”

The pushback on campuses today includes charges of antisemitism against some of the student protesters.

The chanting of slogans like “from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” is viewed by some as a call for the total elimination of Israel.

Jewish students have joined some of the protests, wanting peace in the region. But others say they feel targeted, made to feel unsafe on campus.

Brents recently went to see the student protest of Israel’s war against Hamas on her campus.

Walking away, she saw an Israeli flag, folded up, on the ground. She picked it up, assuming it had been dropped. Then she gave it back to a Jewish group that a table set up near the demonstration.

She told them that she’d been at the other protest but supports Israel’s right to exist. The Jewish students enthusiastically agreed, and they enveloped her in a hug.

“I walked away in tears,” Brents said. “It made me realize how difficult this is for so many people and also that violence is so wrong, just so wrong.”

Brents also countered a narrative being pushed by some conservative politicians, that the students protesting now are “a bunch of losers.”

Sustained protests do tend to draw some people who want to simply agitate, Brents said.

“But for the most part, these are responsible citizens who are going to do something to make the world a better place.”

Mary Sanchez is a senior reporter for Kansas City PBS.