Inside David McCullough’s Relationship with the Truman Library How a Pulitzer Prize Winner Raised the Profile of Local Institution

Published September 22nd, 2022 at 6:00 AM

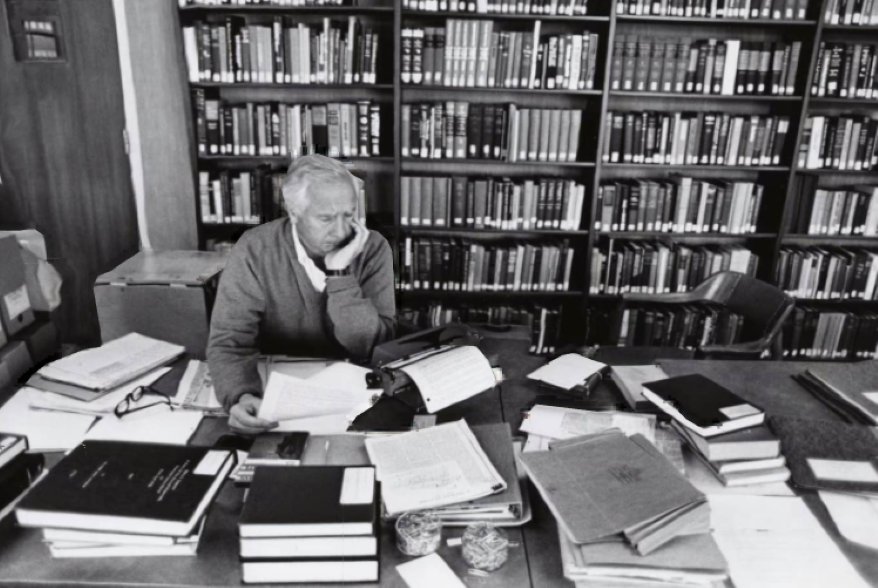

Above image credit: David McCullough (at right), when not in the Truman Library research room, would seek out then-living Harry Truman contemporaries across the Kansas City area for interviews. This photo is from 1989. (Courtesy | Truman Library and Museum)In 2007 the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence observed its 50th anniversary.

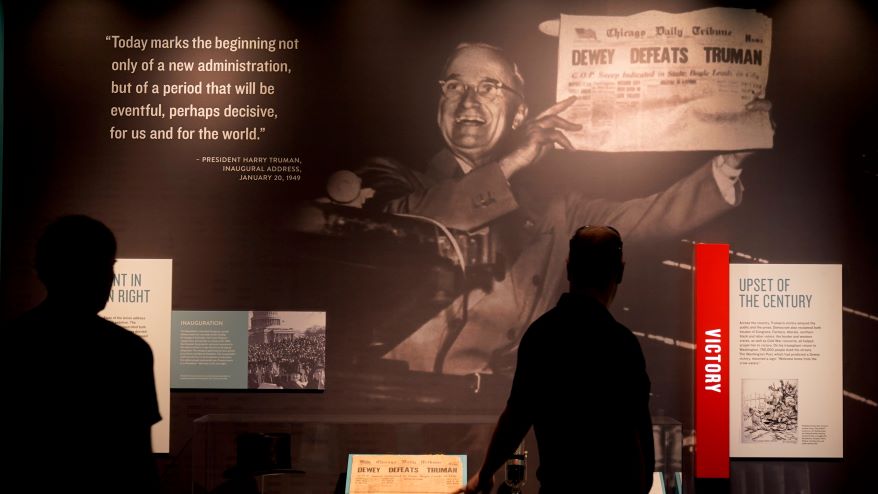

To celebrate, library leaders invited author David McCullough to speak.

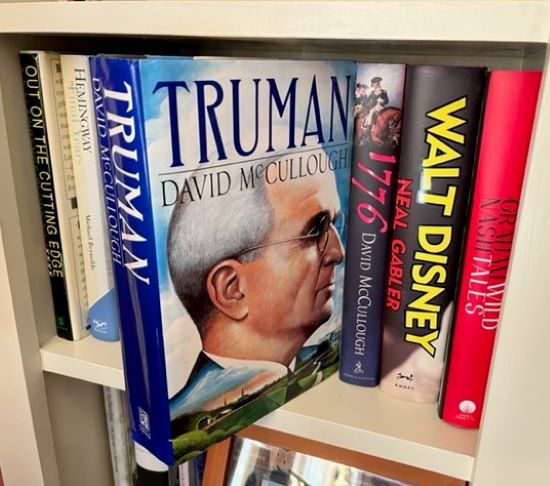

McCullough published a biography of Harry Truman in 1992. It spent 43 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, received a Pulitzer Prize and sold more than a million copies. The book, along with the 1995 HBO film based on it and starring Gary Sinise, had elevated the Truman story to a place in American memory it hadn’t occupied in decades.

In context of that publicity, library officials had mounted a fundraising campaign to finance a $22.5 million makeover of the Independence landmark, and had organized a “Grand Rededication” in 2001.

Before McCullough’s 2007 address a reporter asked him what role he and his book might have played in what ended up being almost $24 million raised to fund the library’s renovation.

“It certainly brought the story of Harry Truman to the country,” he said.

“I feel my own participation in trying to raise that money helped.”

McCullough – who died last month in Massachusetts at age 89 – later would return to the Kansas City area to raise still more money for the library, which unveiled its second major redesign last year.

Today two former Truman Library directors and the current head of the Truman Library Institute, the library’s nonprofit fundraising partner, all agree that McCullough’s book — in the 30 years since its publication — proved helpful in raising the money that allowed library officials to update the library and reposition it on the Kansas City area’s cultural map.

Larry Hackman, who served as library director from 1995 through 2000, describes McCullough’s contribution as more “indirect.” Michael Devine, who led the library from 2001 through 2014, remembers how McCullough continued to put his celebrity in service of library fundraising, appearing at occasional library-related events through 2018.

“David and his book definitely raised the bar for the Truman Library,’ added Alex Burden, Truman Library Institute executive director.

“Over the last 30 years, he helped, and was involved in, some of the most transformational times in the library’s history.”

But the legacy of McCullough’s “Truman” biography goes beyond brick and mortar, and includes the 10 years it took the author to research and write it, the days he spent interviewing local Truman insiders, and one particular day when he took a personal inventory of the variety of trees in Minor Park in south Kansas City.

12-Hour Tour

The Minor Park visit occurred during a 12-hour driving tour of much of Jackson County.

McCullough had been told of the 19th century overland trail swale that was dramatically visible in Minor Park, rising out of the Blue River and heading southwest.

“He got out of the car and started walking around the swale,” said Brent Schondelmeyer, then an Independence bookstore operator who served as driver that day,

“Then he started looking closely at the trees near the swale. He was very interested in what trees could be identified.”

The first chapter of McCullough’s book, entitled “Blue River Country,” would describe not Harry Truman but his Kentucky ancestors who in the mid-19th century had been attracted to western Missouri by its vast wealth of natural resources — trees, especially.

“They counted hickory, ash, elm, sycamore, willow, poplar, cottonwood and oak in three or four varieties,” McCullough wrote.

“Walnut, the most prized, was the most abundant. Entire barns and houses were to be built of walnut.”

McCullough estimated he interviewed some 125 then-living Truman contemporaries while researching his book, many across the Kansas City area.

Any of them might have taken him for an East Coast elite, given his Yale University degree, his Martha’s Vineyard home and his most recent book, “Mornings on Horseback,” which chronicled the young Theodore Roosevelt.

But the local sources put aside any lingering Truman fatigue to accommodate McCullough.

“At first I thought, ‘Oh, another book on Harry Truman,’ ‘’ Sue Gentry, longtime reporter and columnist with The Examiner of Independence, told the Kansas City Star in 1992.

“I really didn’t know who he was or what he had done.”

McCullough gave Gentry a copy of “Mornings on Horseback.” Soon she led him on a separate driving tour of the Independence Truman neighborhood, with one of McCullough’s sons at the wheel and the author holding a tape recorder.

The book had started with a stray remark, when an editor in New York, during a December 1981 meeting, had suggested McCullough follow his book on Theodore Roosevelt with a volume devoted to his distant cousin Franklin, the 32nd president.

“I said ‘No, I want something very different from the life of the Roosevelts, very different from East Coast aristocracy,’ ‘’ McCullough told the Star in 1992.

“Then I said, ‘Besides, if I would write a book about a 20th century president, it wouldn’t be FDR but Truman.

“It just came out of me. I hadn’t spent even three minutes dwelling on it.”

Three weeks later — in January 1982 — McCullough made his first visit to the Truman Library research room.

“It wasn’t until I arrived there,” he said, “before I realized what a woods I was entering.”

Why Truman?

‘Civil War’ Rock Star

On the same day McCullough counted trees in Minor Park, he pressed his face against a glass door at 1908 Main St.

It was the former downtown site of the Jackson Democratic Club, where machine boss Tom Pendergast had ruled Kansas City and Jackson County in the 1920s and 1930s from a small second-floor office.

“I remember David with his face against the glass, counting how many steps there were on the staircase,” Schondelmeyer said.

McCullough eventually would climb the staircase. In 1987, in interviews in the Star and on a local television station, he expressed a wish to meet with extended Pendergast family members, adding during the television interview, “…but I’m not so sure they might want to talk to me.”

Joe Pruett, a Pendergast family member, saw that.

“I thought, ‘What an honest answer,’ ‘’ he told the Star.

Soon Pruett would serve as one of the hosts leading the author up the narrow staircase at 1908 Main St., which readers of “Truman” later would learn included “20 wooden steps” and had struck the author of having “the approach to a dance studio or tailor shop.”

Other local sources included Independence lawyer and Truman family friend Rufus Burrus, Kansas City broadcast journalist Walt Bodine, Independence trails historian Pauline Fowler, Grandview farmer and former Truman neighbor Stephen Slaughter and John Doohan, longtime Kansas City Star librarian.

For McCullough, Doohan had unfolded a map of Kansas City and instructed the author on the respective turfs of the “Goats” and “Rabbits,” rival Democratic Party factions of the Pendergast era.

“My tendency was probably to impose on their hospitality and their willingness to talk,” McCullough said of his sources in 1992.

“But it was so important for me. I believed firmly in reaching the past through living people.”

This component was part of what made the McCullough book memorable, said Michael Devine, former Truman Library director.

McCullough’s biography, Devine said, was one of three to appear in the 1990s, the other two being “Harry S. Truman: A Life,” by Robert Ferrell of Indiana University, and “Man of the People,” by Alonzo Hamby of Ohio University.

“Both of those were good, solid scholarly biographies,” Devine said.

“But what set McCullough’s apart was this very graceful writing style and the way he incorporated the interviews with Truman contemporaries.”

Access to sources usually wasn’t a problem. McCullough already was a prominent author before his 1982 arrival in Jackson County, having published four books and received two National Book Awards.

By the mid-1980s he also had grown familiar to public television viewers.

He hosted “Smithsonian World” and later introduced or narrated episodes of “American Experience.” In 1990 his off-screen narration of “The Civil War,” the Ken Burns documentary, rendered him a rock star among those familiar with Antietam Creek’s stone bridge.

“That really made him a national figure,” Devine said.

“He once told me he had received letters proposing matrimony. Remember, he didn’t appear on-screen.

“People were just responding to his voice.”

In interviews McCullough sometimes would describe his research and writing regimen as a “spell,” or a not-quite-altered state that uninterrupted work produced in him. In 1987 a visitor to his Truman Library research room table got a glimpse of his full immersion method: assorted news clippings, a portable manual typewriter and a three-ring binder, on that day filled with single-spaced typed notes.

(National Archives facility protocols enforced today would not allow such a cluttered work area, Truman Library research room staff members advise.)

He also sometimes carried a watercolor kit. McCullough had pondered an art career when he was young and sometimes would paint landscapes or buildings as an exercise in perspective.

“He would often do a quick watercolor sketch so when he was back in Martha’s Vineyard writing, he could look at it and get his sense of place,” Devine said.

In the fall of 1987, McCullough served as a writer-in-residence at William Jewell College in Liberty.

But more often he stayed in Independence, renting a room from a local resident who made accommodations available to Truman Library researchers.

On those days he walked to the library, mimicking the former president’s post-White House exercise regimen.

He often described his admiration for a particular Independence water tower and later would pause — while seated inside the library research room — to watch visitors stop at the gravesites of Harry and Bess Truman, visible through the windows.

Eventually, a deadline loomed. During one visit to the Star’s library clip file, a brief flash of irritation was seen to cross McCullough’s face, as visitors from the newsroom came to greet him.

By 1991 he was hurrying to submit his manuscript in time for the following year’s presidential campaign. He turned in his last pages on Jan. 8, 1992.

To launch the book in the Kansas City area that summer there was another driving tour, this one led by McCullough, with family members and friends riding inside a small touring coach.

“I want them to be there at what I consider to be one of the highlights of my working life,” he had said a few days before.

On a June Saturday McCullough signed copies of his book at the Truman Library and then at the former Bennett Schneider bookstore on the Country Club Plaza. For almost two hours, a line of Truman admirers stretched down Ward Parkway.

In the public response, some saw a moment that needed to be recognized. One of them was the former president’s daughter.

Banging the Drum

In the spring of 1992, Margaret Truman Daniel addressed fellow members of the Truman Library Institute board.

“She remarked that her father is receding further and further into history and that dynamic works such as McCullough’s book will help accurately preserve his administration,” according to minutes of the institute’s May 9, 1992 meeting.

Planning for a Truman Library renovation dated back to at least 1987, when the National Archives approved a proposal to hire a museum design firm to produce a conceptual plan. McCullough soon joined the board and in January 1994, presented a 15-minute pep talk to members.

“The restoration, renovation, rehabilitation, renewal — whatever we want to call it — of the Truman Library is truly a national event,” he said.

“We are faced in this country today — and we must accept the reality of it — with a rising generation which is, for all intents and purposes, historically illiterate.”

Later he added, “Let’s not just do it, let’s do it right, and let’s bang the drum and raise the money.”

Fundraising dinners organized in 1995 in Washington and Los Angeles the following year attracted A-list guests, with President Bill Clinton attending the Washington event along with former presidents Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford.

Revenues basically equaled expenses, however, and a planned dinner in Chicago was canceled.

In 1996 former U.S. Sen. Tom Eagleton of Missouri became interim institute president and soon helped secure a $4 million federal appropriation, with the understanding that another $4 million would be available if the balance of the funding came from non-federal sources.

But even as late as 1998, a fundraising feasibility study reported a “neutral” attitude toward the Truman Library among philanthropists and foundation representatives across Kansas City.

Library officials, alert to the Truman timeline, in 1998 scheduled 50th anniversary observances of landmark administration events. Those included, in April, an address by Israeli diplomat Abba Eban observing the anniversary of the 1948 de facto recognition of Israel and, that July, a speech by future Secretary of State Colin Powell to note Truman’s 1948 executive order initiating the integration of the U.S. armed forces.

The 1,500 spectators attending the first speech and the 5,200 there for the second represented “the largest audiences by far ever to attend presentations sponsored by the Truman Library,” according to an internal institute document.

In 1998 Larry Hackman, while continuing to serve as Truman Library director, also took on the role of institute president.

Soon institute representatives were meeting with prospective donors closer to home.

Among those visited was Missouri Gov. Mel Carnahan who, with his wife Jean, in 1997 had attended the library’s 40th anniversary celebration. That had included the debut of a new Truman documentary directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Charles Guggenheim — and narrated by David McCullough.

In 1999 Carnahan’s state budget included a $2 million appropriation for the library renovation.

During the same year, institute representatives secured pledges of close to $5 million in Kansas City area foundation support.

In 2000 the institute’s capital campaign exceeded its goal, reaching $23.7 million.

The White House Decision Center, an experiential learning program developed for area students, opened on the library’s lower level in October, 2001. The “Grand Rededication” of the Truman Library, featuring a new permanent exhibit on the Truman presidency, took place that December.

While McCullough’s book had been helpful, the author’s role in fundraising had been “indirect,” said Hackman.

Hackman had advised institute board members to abandon an earlier $10 million campaign in favor of a more ambitious goal, a “Creating a Classroom for Democracy” initiative that would seek to raise $22.5 million.

They topped that goal.

“We succeeded in raising $24 million for first-class exhibits and the White House Decision Center, mainly through reorganization of the Truman Library Institute, building a strong board, (receiving) federal and state funds and tax credits — and hard work,” Hackman said recently.

When Michael Devine, who succeeded Hackman in 2001, arrived at the library, bulldozers were still moving earth and workers were installing new interior walls.

“When I got there most of the money had been raised,” said Devine. “There were still pledges out and it was our job to monitor them.”

For the “Grand Rededication,” McCullough agreed to serve as keynote speaker.

“During those years I think David could have come into Kansas City every week and had a sell-out audience,” Devine said.

More than once McCullough made direct personal contributions to the library, added Alex Burden, who became institute executive director in 2005.

“I can imagine what the board and fundraising committee members thought, that as someone with his own skin in the game, David McCullough would be committed to Truman and would help us as much as he could when we asked him to,” he said.

McCullough’s advocacy for the Truman Library continued with several visits over the years. Before one event, a visitor to a small room in a downtown Kansas City hotel encountered the author sitting with several leaning towers of paperback copies of “Truman,” signing them one after the other.

In 1999 McCullough returned to Kansas City for a 50th anniversary celebration of Truman’s 1949 inaugural ceremony.

“And then fast-forward about eight years, when we were able to convince David to talk on a hot June day out in front of the library,” Burden said.

The 2007 event observed the 50th anniversary of the library’s 1957 opening.

“That was an important time for us, not only to commemorate an important anniversary but it occurred in the middle of our fundraising to renovate President Truman’s Working Office,” Burden said.

The event also provided an example of the author’s almost preternatural poise.

“There we were, all baking in the sun, and he didn’t even seem to break a bead of sweat,” Burden said.

Most recently, in 2018, McCullough returned to be honored at the institute’s annual “Wild About Harry” fundraiser. When it became clear, Burden said, that the institute was nearing a record, McCullough volunteered the necessary amount to clear it.

“We were that close and then David made a $3,000 donation from the stage,” Burden said.

“You can imagine what the crowd’s response was to that.”

Finally, for the institute’s recently completed “STAY TRU” campaign, which raised $55 million for the Truman Library, McCullough had served as a national honorary committee member.

Very Big Book

In the years since “Truman’s” publication, local regard for the biography has manifested in several ways.

In 1997 the Metropolitan Community College of Kansas City Board of Trustees asked Paul Thomson, the school’s founding president, to recommend a formal name for the new Independence campus.

He sought out the sentiments of school employees, who suggested several possibilities, the two most popular being “Frontier” and “Blue River.” On the Friday before he needed to submit his recommendation the following Monday, the school’s head of faculty told Thomson that the employees would accept his final choice.

“So I was sitting on that Saturday morning and something made me get up and get the Truman biography off the shelf,” Thomson said, “and there it was in the title of the first chapter, ‘Blue River Country.’

“And I decided then that must be the name. On Monday I sent the recommendation for approval. It was adopted unanimously.”

Years later Thomson told the story to McCullough.

“He seemed almost surprised to hear it,” Thomson said, “as if this had been a kind of ripple effect he hadn’t counted on.”

There would be others.

In 2004 a Kansas City Public Library committee agreed on a list of books whose spines would be reproduced as high as 28 feet as part of a “community bookshelf,” an architectural feature on the south face of a West 10th Street library parking garage.

“Truman” would be among them, along with “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “Fahrenheit 451.”

The following year Don Reimal, an Independence City Council member since 1994, resolved to run for mayor.

While waiting for the city clerk to arrive on Monday morning, Reimal spent two weekend nights inside Independence City Hall’s front foyer, taking advantage of a policy that allowed candidates waiting to file for public office to escape inclement weather.

Reimal brought a copy of “Truman” and a canvas camping chair.

“I did this to show the people that I am very serious about this and that I truly want the position,” he said.

Reimal filed for the mayor’s office and won, serving two terms.

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author. He is serving as president of the Jackson County Historical Society.